A Malabar Saga

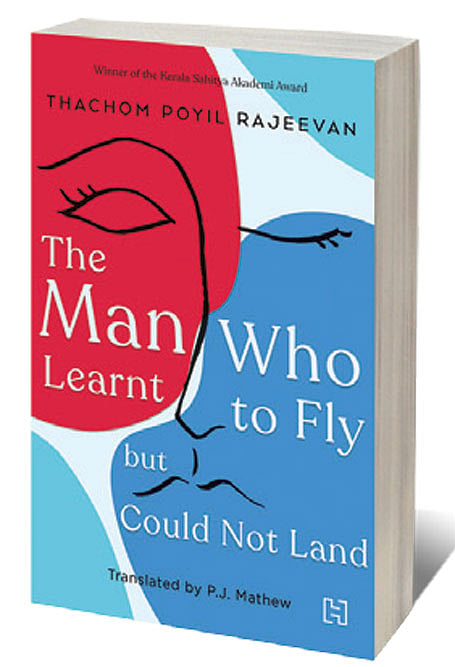

TP RAJEEVAN’S NOVEL The Man Who Learnt to Fly but Could Not Land, which won the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award, rolls out an epic canvas with an assemblage of characters. In the garb of a biographical fiction of a non-existent writer, the novel essentially unravels a sociopolitical history of pre-Independence Malabar of the 1930s-1940s.

To those familiar with that period, not all the protagonists come across as fictitious. Some real figures in history loom large across the text. And some familiar figures parade under a fictional name, the fictional characters being just links connecting the gaps that happen in period research. Those narratives of unsung heroes reach out with the undocumented lives of their loved ones and we get a glimpse of folks who do not even lay a claim to a footnote in history.

The protagonist, KTN Kottoor, is someone who has inherited the idea of freedom from his father and holds on to it dearly, all his life—only to vanish into thin air as the country raises the Tricolour in full pride of freedom. The novel is a personal and political narrative built around his life but visualises much more.

We are shown how KTN’s father, Kunjappa Nair, himself a member of the landowning gentry, was the first one to introduce the Tricolour to a people untouched even by the idea of politics and literally ‘lead’ them into the concept of freedom. And how the idea of real freedom is taken up by the son, who, even as a youngster, was involved in printing ‘pamphlets’ and political magazines. But he soon becomes exposed to the true colours of politics. His idealism does not find favour with either the landlords or the socialists in the ‘Congress’ movement. However, he goes on to write and speak his mind and is pushed into a corner as his philosophy is not in sync with the evolving politics. As a result, KTN goes to jail, and when he returns, he is rejected by the very people he thought were his breed.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

He continues to write for social change, but his personal life spins into turmoil as he rebounds into a socially unacceptable pattern of life. His aunt who brought him up dies of a broken heart watching his ruin. The many women in his life, including his blind wife, are left behind as he finally goes away on a quest of himself. KTN’s story also reveals the lives of people in a turbulent time where society and politics stand at a turning point of history.

Rajeevan’s first novel, Palerimanikyam, Oru Pathirakolapathakathinte Katha (Paleri Manikyam, the Story of a Midnight Murder), which he first wrote in English and then in Malayalam to great acclaim, is also a historical narrative.

In his opening note, TP Rajeevan mentions how he learnt of the freedom struggle not from textbooks but his surroundings. He emphasises the need for an agrarian and subaltern understanding of history. The novel has beautifully captured what could be some of these lost moments.

Rajeevan’s prose abounds in symbolism and adapts to the mood of the drama played out in the text, in both the novels. Yet, at times, it’s deceptively simple, or layered or crisp, as the story demands. But, like his poetry, his prose is always intense. The tapestry he weaves the story into is an almost magical one and requires a wordplay and extraordinary imagery. It abounds in cultural idioms. A translation of such a text is therefore a daunting task. But the translation of the novel, by PJ Mathew, meets the challenge competently. The translation closely follows the original in both text and understanding, making the reading of it a pleasurable experience.