A Dragon in the Garden

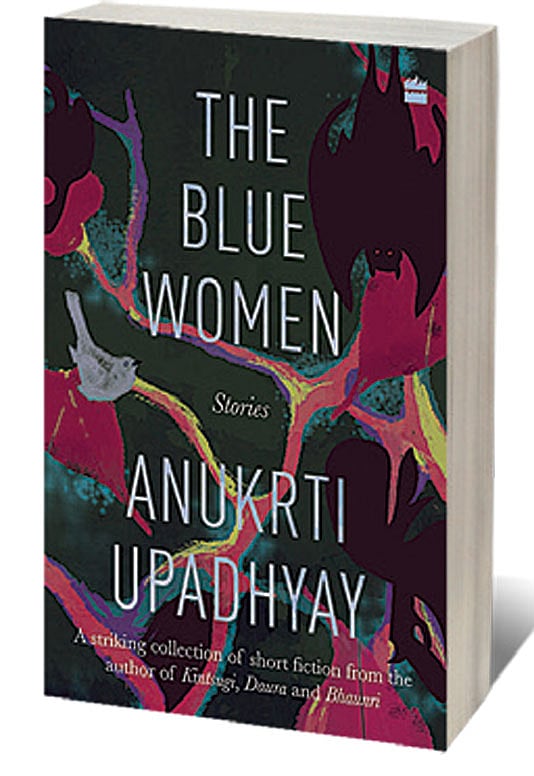

A LINGERING UNCERTAINTY lies at the heart of Anukrti Upadhyay’s anthology of stories titled The Blue Women. The characters who drive the narratives are searching for solutions to ride over uncertain predicaments. But however life-changing these uncertainties turn out to be, they take a back seat, as Upadhyay leads readers into lush situations to watch the stories unfold through an intimate lens. Each story, though unconnected with each other, is linked by the tangled paths drawn up by the author.

The anthology opens with a story bearing the title of the collection. In ‘The Blue Women’, the unnamed protagonist, who drives a taxi for a living, suddenly faces a strange problem. She sees a blue glow on some of her female passengers that intensifies to indicate a tragic event in their future. The strange glow, a cosmic warning revealed only to her, unsettles her enough to stop taking female passengers. However, fate cannot be tricked and the blue glow once again appears inside her car as if taunting her to take action.

Some of the stories are set in restaurants and canteens where food jostles for attention along with the dialogues and ruminations of the characters. In stories such as, ‘Dhani’, ‘The Queen of Mahim’, ‘Shawarma’ and ‘The Big Toe’, the restaurant/canteen setting allows for rich descriptions of foods as the diners try to make sense of their lives.

Upadhyay often presents stories within stories, nudging the reader to pay attention to the narrative playing out in the background in addition to the one being recounted. In ‘Dhani’, the narrator who is a technician to an audiologist, finds himself straining to make sense of the couple with whom he is forced to share a seat in a crowded restaurant. As the couple recount the pebbled journey of their life, the narrator’s story unfolds quietly in the background leaving the readers to seek a connection between their journeys. In ‘The Big Toe’, the narrator who calls himself a collector of stories, has no option but to share a table with a man “with sad eyes”. In an attempt to make his companion relax, the narrator tries to engage him in small talk. The man responds by talking about his friend who has an extra toe and how it has made the man’s life miserable. As the narrator gently probes his companion for more details, he unknowingly lets out particulars from his own life, seemingly insignificant but important to him nevertheless.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Upadhyay has used the rhythms of nature to good effect to create surreal backgrounds against which the stories unfold. A dragon in the garden, a bat in the tree battling a venomous snake, termites and insects bulldozing their way inside homes, all evoke fascination and horror in equal measure. In a way, they serve to depict how lines blur as imagination distorts when connections within families break down.

Even though the stories revolve around multiple themes like domestic violence and alcoholism, the trauma of disturbance and displacement forms the main framework. In ‘Sona’, a young girl has a crush on her step-father and sees her mother as a rival standing in their way. In ‘Insecta’, a boy stumbles when he is sent to a prestigious school to continue the tradition of his forefathers. His passion and knowledge about insects, which earlier had been a source of pride for his parents, now turns into a source of horror as the young boy’s mind strains under uneasy experiences.

Readers might be reacquainted with Meena, one of the main characters in Upadhyay’s previous book, Kintsugi (2020). We meet Meena in the last story, ‘The Satsuma Plant’ and while she seems to have done well professionally, her personal life continues to reel.

In this collection of stories, the author nudges the reader to look at the unexpected ways in which people pushed to the margins react, especially when their voices are stifled. The landscapes and the uncertain lives of the characters in The Blue Woman linger with you long after you finish the book.