The Day After

How being 100 km away from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster changed my life

Samantha de Bendern

Samantha de Bendern

Samantha de Bendern

|

08 Apr, 2013

Samantha de Bendern

|

08 Apr, 2013

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/chernobyl1.jpg)

How being 100 km away from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster changed my life

Before the world’s worst nuclear accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant on 26 April 1986, I was full of the certainties of youth. Then, overnight, or should I say over the course of a few beautiful spring days, everything changed and I stepped reluctantly into adulthood. Those who remember those days talk of the same thing: the weather. It was unseasonably warm, hot enough to sunbathe, and the lilac blossoms came early, infusing the parks and streets of Kiev, the Ukrainian capital, with an aroma of lemons, vanilla and roses. I was studying Russian there and having the time of my life. As a Russian-speaking British student in what was still the USSR in the midst of the Cold War, I was regarded by the KGB as a potential future adversary and under constant surveillance. They took it seriously, I didn’t. Indeed, here, safely ensconced behind the iron curtain, I felt liberated from a far more significant entity than the KGB: my parents. I studied hard and partied hard, high on the adrenaline of playing hide-and-seek with those who were keeping tabs on me, and, of course, on Soviet vodka. I felt totally free for the first time in my life in spite of the restrictions of a totalitarian state because none of the rules of my world applied.

So it was with tremendous irritation that I listened one Monday morning to a panicky phone call from my parents in the UK warning me about a nuclear “incident” somewhere close by. Other foreign students had received similar calls. Someone had a radio that captured BBC broadcasts warning of an unexplained radioactive cloud emanating from somewhere in Western USSR, where we were located.

I ignored the news. It was interfering with my fun. I thought it was probably no more than a mixture of over-anxious parents keen to find any excuse for their children to come home and exaggerated anti-Soviet propaganda by the BBC. I skipped class and went to the ‘beach’, a small strip of sand on the bank of the Dniepr river that flows through Kiev, for a sunbath. It was probably the worse thing I could have done.

Further North, in Sweden, high levels of radiation had been detected the day before and suspicions were growing that something very serious had gone wrong in the USSR, from where the wind was blowing. The Swedes asked Moscow for an explanation but were met with a stony silence. As radiation levels continued to rise, the Swedes began to take emergency anti-radiation precautions in areas close to the Soviet border. They advised parents to keep children away from sandpits and avoid using rainwater, as both sand and water are extremely efficient vehicles of radioactive contamination.

That was 1,100 km from Chernobyl. We were 100 km away, and the news blackout was total.

As more alarming reports began to filter through the radio and over the phone, a wave of collective hysteria began to rise among foreign students. I was still in denial, sulking with a small group of non-believers. We had distanced ourselves from the main group, but I remember seeing a lot of tears and pleas with our group leader to organise an evacuation. Eventually, on 29 April, orders came through from the British embassy in Moscow that we were to pack our bags and leave by any means possible.

It must have been about then that I started to cry. I am not really sure what triggered my tears, but once they started, they would not stop. It may have been because a friend who worked in a Kiev hospital told me that a whole wing had been cordoned off with rumours of young men with severe burns being treated there. When I asked my teacher what he thought about this ‘nuclear accident nonsense’, he said he couldn’t believe that the Soviet government would allow its children—his children—to walk the streets unprotected if they were really in danger. I saw fear and doubt in his eyes.

Worried mothers had begun dressing small children in ridiculous woollen hats to protect them from radiation. Rumour had it that vodka offered good protection—for adults. Some opted for the hats and the vodka. Tragically, simple iodine tablets would have protected the population from radioactive iodine, which gets into the thyroid gland and is particularly lethal to children. But distributing these tablets would have meant admitting a problem.

I could no longer remain in denial, but I did not want to leave either. I felt like a rat leaving a sinking ship, abandoning my friends and their children to face whatever invisible poison was seeping into our bones. I was also, selfishly, dreading going home. I preferred to face the uncertainty of danger to the certainty of boredom in an English suburban town. I did not realise then how lucky I was to have a choice. My whimsical attitude was that of a privileged Westerner who could play at tipping her toes into misery, with the certainty that she could leave when things got too uncomfortable.

It was not that easy to get out of Kiev. Foreign students needed permission from the Soviet authorities to leave the city and country. Once that was secured, we faced the additional hurdle of finding transportation. By now panic was beginning to spread in Kiev. A brief broadcast on television nearly 72 hours after the accident had mentioned a minor incident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, and rumour mills had started whirring in full force. People were scrambling for tickets on buses and trains leaving Kiev to go south or east, away from the wind. Seats were hard to come by.

We finally boarded a special train full of soldiers moving east. We were placed in clearly separated compartments. Most of our group immediately started to party and celebrate our escape. I was in a dreadful mood: furious, sad and confused. I had another episode of tears as the train pulled out, and retreated into my shell.

I cannot remember precisely how I separated myself from the rest of my fellow students, but at some point I found myself looking through double-glass doors into a military carriage. A young soldier more or less the same age as me looked back at me. I smiled. He smiled back. I waved, and he waved back beckoning me to come over.

I was young, he was cute, the sun was setting on the golden Ukrainian plains rolling past, and I was feeling reckless. I stumbled across the connecting passageway linking the two carriages, and he took hold of my hand to steady me while opening the door into the military compartment. His name was Stanislav.

We started to talk and a few other soldiers joined in. I explained that I was British and they joked that their patriotic duty would be to arrest me. One of them said, “Listen guys, she may be a foreign capitalist imperialist, but she looks just like us… maybe she wants some food.” So we ate, talked, sang songs like carefree teenagers anywhere else in the world. Stanislav asked me about the nuclear accident we were supposed to be fleeing. I told him whatever I knew, and he said, “If I ever find out that this accident really happened, and you knew it before me, I will lose all faith in my government. I will no longer be able to serve in this army. I cannot believe that something so terrible would be kept from us.”

Because the accident happened so close to the West and the fallout was registered as far away as the UK, pressure from the international community made it impossible for the Soviet government to keep silent for very long. By early May, the Soviet population was officially informed of what the rest of the world already knew. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet men and women like Satinslav lost their faith when they realised that their government had preferred to sacrifice human lives rather than lose face by admitting the disaster in time.

Historians today concur that the political fallout of Chernobyl was in a way greater than the nuclear fallout, as the population was suddenly confronted with the unequivocal reality of the lies their system had been built on. The disaster was one of the triggers for what became known as glasnost or openness, Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of uncovering the truth about the past and insisting on transparency in the present. He thus opened a Pandora’s Box from which emerged unspoken truths about the Gulag, the revolution, corruption and cronyism in the Communist Party, mass deportations, environmental disasters and nuclear contamination in remote areas of the empire, that 70 years of unaccountable rule by the One Party State had left in its wake. In many ways, Chernobyl was the first rip in the iron curtain that finally came apart with the collapse of the Soviet Union five years later.

My train journey drew to a close. After a night of heated but friendly arguments with my soldier friends, we were greeted by a horde of hysterical Western journalists as the train pulled into Moscow. A microphone was thrust into my face, and a young AP reporter shouted, “So how many dead bodies have you seen on the streets of Kiev….?” All I could remember was the sun, the walks in the park and carefree days. Dead bodies? I felt a rush of anger at this obvious distortion of facts. I dropped my bags and ran to where the soldiers were. I wanted to engage in the ultimate provocation and kiss my soldier friend goodbye in front of the Western press, but the senior officers stopped me from getting too close. So I just blew him a kiss and walked away, tears rolling down my cheeks, resigned to the idea of going home.

The rest of the day passed in a daze. We were sent for blood tests and had Geiger counters run up and down our bodies. I was unable to decipher their clicks and creaks, and no one thought fit to tell us whether we were radioactive. We were put on board a Japan Airlines flight from Tokyo to London via Moscow that had some free seats. Before we were allowed into the plane, Japan Airlines personnel stripped us of our clothes and gave us white jumpsuits. We looked like survivors in a holocaust disaster movie, much to the horror of our fellow passengers who stayed as far away from us as possible: for historical reasons, the Japanese are somewhat sensitive to the idea of radioactive contamination…

At London Heathrow, we were ushered into a separate arrival room, a sort of glass cage in which we could safely be photographed by the press. More Geiger counters hissed over our bodies and bags, and some clothes, including mine, were taken away. We showed exposure to radiation that was equivalent to about a year’s permitted dose, nothing overly dramatic but not a pleasant thought either. Once the press left and the lights were dimmed, we were relieved of our jumpsuits, allowed to get dressed, and told to go home.

This left me with the uncomfortable impression that the fuss about the jumpsuits had been more for the benefit of the media than out of any real concern for us. The next day, when I saw a tabloid headline, ‘British students lifted from Red Hell Hole’, my discomfort grew stronger.

I felt surrounded by lies. I also felt used, a mere pawn in a game of tit-for-tat between superpowers. By then, I had had access to serious news reports on the incident and knew that the Soviets had been lying. But I could also see that my own press was, if not lying, grossly distorting the truth by putting out sensational headlines to demonise the ‘Evil Empire’. A void opened up inside me as I realised that my certainties had disappeared. I knew deep down that headline exaggeration was far less of a crime than putting hundreds of thousands of lives at risk, but I could not shake off the feeling that there were no good guys or bad guys anymore, just shades of truth and lies, to be used by whoever happened to be stronger.

As the years went by, I revisited Ukraine several times and worked on issues relating to Chernobyl in an intergovernmental capacity. I met school teachers and parents in Belarus, the area worst affected by the fallout. They all told me of the high incidence of thyroid cancer and birth defects among children born just before or after the disaster.

Today, the children of Chernobyl are becoming parents themselves and a legacy of illness is being passed on to a new generation. I also met mothers and wives of ‘liquidators’, the young boy soldiers who had been sent to extinguish the fire in Chernobyl after the accident with just white cotton suits and flimsy hats for protection. Many died horrible deaths in the weeks and months that followed.

As for me, I am healthy and have two healthy children. I was close to the accident, which the International Atomic Energy Agency has since described as ‘400 times more potent than the atomic bomb dropped over Hiroshima’, but the wind was blowing away from Kiev. Most importantly, I was able to leave and avoid long-term exposure to contaminated food and groundwater. I was lucky because fate had determined that I be born in a part of the world where citizens have a voice and hold governments accountable for their well-being. I have never stopped wondering, however, whether our forced evacuation was more of a publicity stunt to show up Soviet inadequacies than an expression of genuine concern for our well-being. It was probably a bit of both.

This 26 April, I will light a candle wherever I am, just as I have done for the past 27 years, and ask for forgiveness: for having left, as well as forgiveness for not having appreciated at the time how lucky I was to have had the choice. I will also say a prayer for all those the world over whose health and lives have been sacrificed at the altar of truth in order to save the face of governments or corporations—a prayer for those who do not have a choice.

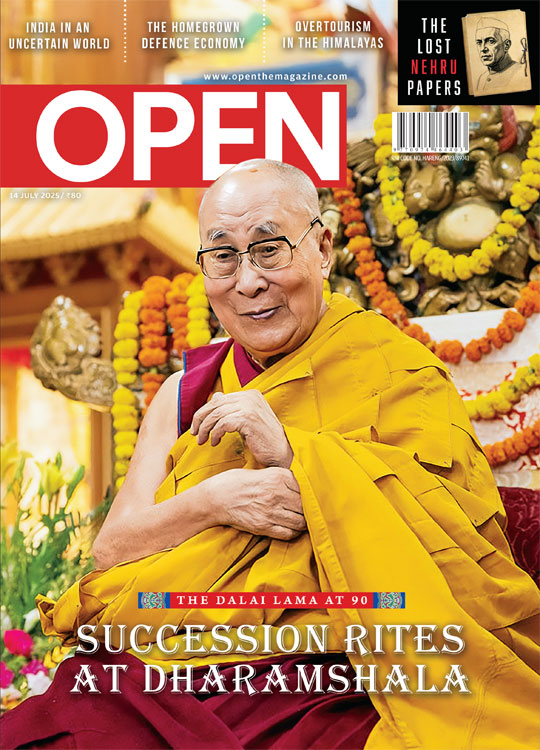

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

From Entertainment to Baiting Scammers, The Journey of Two YouTubers Madhavankutty Pillai

Siddaramaiah Suggests Vaccine Link in Hassan Deaths, Scientists Push Back Open

‘We build from scratch according to our clients’ requirements and that is the true sense of Make-in-India which we are trying to follow’ Moinak Mitra