The Family Business Hash Tag

An afternoon with three generations of a family of drug dealers

An afternoon with three generations of a family of drug dealers

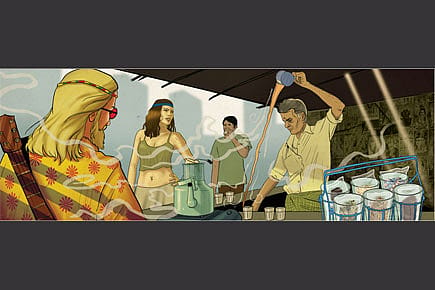

In a busy bazaar in New Delhi is a dingy tea shop that stands apart only because of the kind of people who inhabit it at different hours of the day. Tourists, locals and hippies are gathered in the small room. An old man with dreadlocks and tattoos sits quietly in a corner puffing away on something that looks like a cigarette but has the unmistakable sweet smell of marijuana. At the entrance, on an elevated platform is a counter manned by a stout ageing man whose eyes keep alternating between the room and the street. He is the owner of the shop. His name is Madan and he is 62 years old. Eventually he walks up to the man in dreadlocks and whispers something that makes him stub the joint. He then walks back to his counter and lights an incense stick.

A constable shows up, struts through the shop and settles down. The helpers scurry to take his order. For a while, all attention is on him as he downs his tea and toast. He leaves without paying, nodding at Madan. Once satisfied that the constable is gone, Madan screams at a helper to take my order. Alcohol is available even though it is not on the menu. Five minutes later, I get a plastic cup meant for coffee. It's filled with beer. People come and go. Every once in a while, Madan disappears with them into a room, a hole in the wall at the farthest end of the shop.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

It is almost an hour later that a black Honda bike pulls over next to the shop. A middle-aged man and handsome boy step down. They are Madan's son and grandson. They make their way to my table and ask if I have been comfortable. I smile. "Would you like to move inside?" asks the younger one. The room is stuffy and filled with touristy artefacts, bongs, marijuana crushers, paperweights and a poster on travel reservations and currency exchange services.

"Good evening. I am Rajeev, Rakesh's father," says the middle-aged man. "I understand you want to tell our story. What is it that you want to know?" He then pushes open a glass panel to reveal shelves, takes out four wooden boxes and puts them in front of me. He has a flair for theatrics as he opens their lids one by one, not taking his eyes off me. The boxes are neatly lined with marijuana sheathed in plastic. "Malana Crème, madam. The finest quality," he says, urging me to touch and feel its texture. "Would you like a smoke?"

I decline. He scoffs. Rakesh, who is 26 years old, tells his father to calm down. "He is just trying to push you and see if you are part of a sting."

Rajeev is now starting to crush some marijuana. He tells me he has just returned from a trip to Himachal Pradesh with "the freshest, most beautiful stock" that I can imagine. At some point, Madan comes in, shuts the door and starts talking about someone named Shivraj who has returned after spending one-and-a- half months in jail.

"He was caught with 6 kg of marijuana, madam, but after a settlement, they charged him with three. He is an old friend," says Madan. He says the police have a new-found enthusiasm for cracking down on marijuana dealers. "A couple of years ago, it was easier. But now one has to be very smart."

I hold my tape recorder closer to them and they stiffen. "No recording madam. We are not stupid. Turn that thing off or leave," says Madan. I explain that I need to get everything they say, but he doesn't relent. "We will talk slowly," he says.

The conversation resumes. Madan Kumar came to Delhi 30 years ago from a small village in eastern UP. They were farmers with meagre land holdings. "I had hoped for a better life here. For the first five years, I did odd jobs, but the income was so dismal that after meeting my living expenses, I barely had any money to send my family." There were four sisters and a mother to look after. "After five years of living hand to mouth, I went home and sold off almost all my land." He used that money to set up a modest tea shop. "For the first few years, it was the shop that really had my attention, but then, how much can one make selling chai? I had bigger dreams," he says.

He had been a man who didn't mingle too much but now he started to observe people in the neighbourhood and making small talk. "Once I let my guard down, they began to trust me." A friend opened up to him about his drug business and asked him if he wanted to join in. At first, Madan declined; he was scared. But the money was easy and hard to ignore. So he took the plunge. "I went to my friend and asked if he could set me up. He agreed to help me if I gave him 20 per cent of what I made."

In 1987, Madan went on his first trip to Kullu Valley in Himachal Pradesh with his friend. They stayed there for 14 days, by the end of which he knew everything and everyone he needed to know. "We spent our days with locals—eating and sleeping in their homes, watching them discuss their crop and understanding the details of doing business with them." He learned how to differentiate between different varieties of marijuana by smell. "I had never smoked in my life and didn't intend to start now that I was getting into the business."

According to him, it was simpler back then as the villagers were friendlier and it was easy to negotiate with them. "Things are different now because of so many international players coming in. Sometimes, supply cannot meet the demand and things get tricky."

The first lot of hashish that he got to Delhi was in hollow statues of Hindu deities. "They looked like regular tourist souvenirs and were safe to store. The money I made that month, Rs, 80,000, was more than I made in half a year. I knew there was no looking back."

Along with his son and grandson, Madan now has a mid-sized family business selling marijuana in the form of hashish and hash oil extracted from the cannabis plant. They cater directly to customers who they first screen. "If we don't like them, we don't deal with them. Being not too greedy keeps us safe," says Madan. They don't need to be. One kg of hash from a mediocre crop can bring in Rs 150,000 with a profit margin of 40-45 per cent. When the quality is pure, even 10 gm sells for Rs 2,500-3,000, depending on what the customer is ready to shell out. So too with hash oil, which is rare to find in the region and has an average price of Rs 3,000 for a small vial. Most customers are tourists, college students and young professionals. In a month, Madan sells up to 5 kg.

"Everybody does it here, madam. You want drugs, go into any shop and convince them that you are genuine. Within half an hour, you will get what you need," the 62-year-old assures me.

In the 26 years that he has been operating, Madan has been jailed several times, sometimes for months on end. He now tries to keep a low profile. In the early 1990s, on his way back from a regular sourcing trip, he came under the scanner for the first time because of a tip off "from a rival who was jealous of how well I was doing. Within half an hour of making my first purchase, I was tracked and caught." The police found 3 kg of marijuana on him. He spent four months in jail and had to pay Rs 50,000 to get out. "It is no big deal. Unless you are caught with a huge amount on you, you are safe. Also marijuana is still tolerable; it is the chemicals that they are really after."

"We don't deal in chemicals," says Rajeev, who is now visibly stoned and has a vacant stare. "But if you need something and are a loyal customer, we will get it for you. Anything from smack to heroin is available on request." Rakesh, who is starting to get restless, glares at his father to shut up and decides to take a walk. Rajeev first got involved in the business when Madan was jailed and a shipment needed to be bought into town. Madan says, "So I called for him from the village and sent him to collect it. He got stoned on it, the poor idiot. He had never seen such a thing before, and where we come from there is only ganja." Rajeev laughs and nods at his father. "I was just 20," he says.

The rest of the family is in the village and have no inkling of the business. They think we struck gold with this shop," says Madan, like a proud patriarch. "We provide for them and visit them often. It keeps them happy. What they don't know is none of their business."

Rakesh returns, a small boy with light brown eyes and hair in tow. The kid rushes to greet Rajeev. "His mother is an old friend. A French hippie who now alternates between India and Germany," says Rajeev. "He is also my half-brother," says Rakesh, almost in disgust. Madan pats him on the back to pacify him. "I have to go soon to deliver something," Rakesh says. Madan stiffens and turns to him, "How many times have I told you not to deliver [contraband] yourself. You are not going. Send someone." He turns to me, "It is safer that way."

He says the last time they went to deliver packages themselves, they were almost caught. "I am getting old now. I don't want to spend my days in jail or see my family suffer. We have to learn to play it smart. Once you are caught, you are marked and monitored. Look at all the things I have to do to keep up appearances," he says, referring to the shop. "There is no way I am going to jail again. Madam, there are thousands like me in this area. It is not as easy to mark me out as you think it is."

To conduct their business, they have to deal with extortionists among cops and others who have a whiff of what they are up to. "There are so many scavengers who come looking for a free deal. We have friends in all kinds of places and sometimes to shut them up, we have to make them happy," says Rakesh. "You never admit. Once you admit, you're in trouble. Just make them happy. Give them money, food and politely tell them that you have moved on in life and they will leave you alone for a while."

There is a knock on the door. It is the helper saying that Madan is needed outside. It is also my cue to leave. Just like that, unceremoniously, the meeting is over. As I step out into the hot dusty evening, a fresh lot of people are making their way to the tea stall. Madan is in conversation with a young affluent-looking man. Rajeev starts playing with his mobile phone. Rakesh offers to drop me to an autorickshaw. I tell him I can manage, but he insists. I walk onto the street with him. As I leave, I see Madan telling the young man to go to the far end of the shop towards Rajeev. Once outside the bazaar, Rakesh waits for me to settle in the vehicle. He then leans over and, before disappearing into the crowd, says: "I hope you know that I can't stand this life. All this is temporary for me—until I make it big in the modelling world."