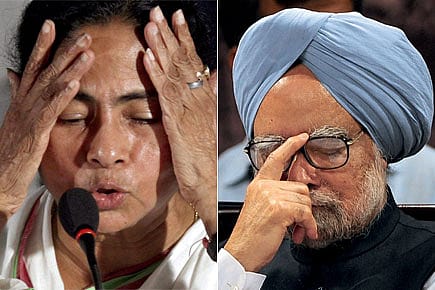

The Mamata Effect: Mulayam Acts Tough But Maya May Help

The Congress knows that the SP can at best be a short-term ally, but it hopes the compulsions of self-interest ensure the BSP's support

Ahmed Patel's SOS to Mulayam Singh Yadav moments before Mamata Banerjee threw her bombshell of 18 September marked the start of the Congress' Plan B to save the UPA Government. The SOS prompted the SP Chief to rush to Delhi within hours—a day before his scheduled arrival.

The Trinamool Congress' decision to withdraw support to India's Government has left the ruling party in political flux, with its firefighters frantically working out all manner of new numerical combinations in the Lok Sabha. While the first call made was to Mulayam, the Congress may have to make several other calls as well. Sooner or later, the party will have to shift its attention to Mayawati, leader of the BSP, who, like Mulayam, is an external supporter of the UPA at the Centre.

The Trinamool Congress, with a Lok Sabha tally of 19 MPs, was the second largest party in the UPA after the Congress, with 205. Without the Trinamool, the UPA Government would be reduced to 254 seats in the House, which is 17 less than the halfway mark of 271. If it weren't for the external support of two tempestuous Uttar Pradesh rivals—the SP with 22 MPs and the BSP with 21 seats—apart from Lalu Prasad's RJD, which has four MPs, and HD Deve Gowda's Janata Dal-Secular with three, the Government would have been at immediate risk of being voted out of power on the floor of the House.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Mulayam Singh Yadav's promptness in rushing to Delhi does not, however, mean that he has given up his wait-and-watch game of politics. For, despite these developments, the SP has not been able to desist from sending out mixed messages. Even as Mulayam responded to Ahmed Patel's call, SP General Secretary Ram Gopal Yadav said the Government should not count on his party's support as a done deal. "This government has lost its credibility," in his words, "and shouldn't take our support for granted."

One may calculate that with the SP on board, the UPA's strength in the Lok Sabha remains well above the halfway mark even if Banerjee actually carries out her threat to withdraw support. (At the time of going to press, the party had said it would do so on Friday, 21 September).

But that calculation is riddled with loopholes. And one of them is the SP strongman's desperation to become Prime Minister of India. Hidden in this aspiration of Mulayam are several options that the SP has already started weighing as it prepares to hobnob with the Congress.

There is reason to compare the current situation with what happened after the Indo-US Nuclear Deal during the UPA's first term in power. Another party that drew significant strength from West Bengal, the CPM, had pulled out along with the CPI, but Mulayam Singh stepped in to bail the UPA out. In doing so, he extracted a heavy price, so much so that most Congress leaders were quickly seen yearning for the days when the Left had been an ally. This time round, while the broad situation may be similar, the SP's compulsions are somewhat different—and Mulayam Singh's ambitions much larger.

Note that the SP began its preparations for the next Lok Sabha polls immediately after it swept the Assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh in March this year. Though the next general election is two years away, the party is already in the process of finalising its candidates. "The observers that the party had appointed for all parliamentary seats in UP, in order to identify suitable candidates for each of them, have submitted their reports," says Rajesh Dixit, the party's observer for the Pratapgarh Lok Sabha constituency. "Soon, the party will start finalising its list of candidates," he adds.

An early election suits the SP as well as it suits the Trinamool Congress. In UP, for example, the SP is still riding high, and it is too early for anti-incumbency to set in against the SP government there. Also, the recent spate of communal flare-ups in the state, the latest one being in Ghaziabad, has led to a high degree of Hindu-Muslim polarisation, and the resultant tension suits the SP as much as it suits the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Yet, the SP would not like to be seen as the party pulling down the Government if such an event were seen to go in favour of the BJP, which is more than mildly keen to return to power at the Centre. The SP counts Muslims as a core part of its vote base, and it is obvious to Mulayam that their support can make or mar the SP's prospects in any election it contests. Thus, any move by the party that would appear to strengthen the BJP runs him a high risk of alienating Muslim voters; this is something he has been careful not to do, at least not since his party's drubbing at the BSP's hands in UP's 2007 Assembly polls in which he was seen cosying up with former BJP leader Kalyan Singh. The SP, while extending the UPA support for now, would therefore be looking for a suitable time to force an early election at some point when a political opportunity arises that doesn't risk losing Muslim votes.

In any case, the UPA must not expect Mulayam's support without a price. Sources, while explaining various options being weighed by the party, have ruled out the possibility of the SP joining the Government. Nor do they expect to prop the UPA up for very long.

The SP, it is clear, will drive a hard bargain even for short-term support. For example, in return for bailing out the Government, it may ask for a financial package for Uttar Pradesh, where its state government could do with some extra cash. And yet the SP is unlikely to give up its anti-Centre rhetoric as Mulayam fancies his chances as PM through a possible 'Third Front' in case of a fractured verdict in the next Lok Sabha polls.

It is for these reasons that Mulayam Singh Yadav, even while responding to Ahmed Patel's late evening call, has raised his ante. "If the decisions to hike diesel prices and bring in FDI in multi-brand retail aren't reversed, the party's parliamentary board will meet after September 20 to review the situation," Mulayam Singh Yadav said, "In that meeting only our party would decide on its future course of action."

Indeed, the call for an all-India bandh on 20 September issued by various parties, including the SP, as well as traders' organisations, has assumed a completely different dimension now. The kind of response the call gets in the country, particularly in UP, is also likely to have a significant bearing on the decisions that Mulayam Singh ultimately makes in his party's parliamentary board meeting scheduled later.

A tricky relationship is what the Congress can expect with Mulayam. But that by no means is the only option for the Congress at this juncture.

The 'third M' of politics, Mayawati, also has enough numbers at her command to play UPA saviour. And the support of the BSP, because of its own precarious political circumstances, may prove to be much more durable than what the Congress can expect of the SP.

With her 21 MPs in the Lok Sabha, Mayawati can keep the Government intact even if Mulayam decides to go the Mamata way. Like Mulayam, she too has spoken out against the fuel subsidy cuts (LPG and diesel price hikes, that is) and the UPA's retail-FDI decision, but has given the Government time till 10 October, when, after holding a public rally at Lucknow to mark the death anniversary of BSP founder Kanshi Ram, she plans to sit down with her colleagues and chalk out the party's future course of action. What is additionally significant is that Mayawati has kept herself away from the 20 September bandh.

Moreover, the Congress may find comfort in the fact that unlike Mulayam, Mayawati—who suffered an electoral defeat earlier this year—is not pushing for an early Lok Sabha election. She is not in power anymore either and has no reason to worry too much about the consequences of accepting or rejecting FDI in the multi-brand retail sector. Her own core constituency of Scheduled Castes still largely remains unaffected by any decision of this nature. Nor does Mayawati see any space for herself in any Third Front where Mulayam wields clout. The last Third Front initiative she took was ahead of the previous Lok Sabha polls in 2009, and nothing came of it. In fact, it started crumbling even before the first vote was cast that summer.

Mayawati is also beset with her own inner-party problems. Ever since the BSP was trounced by the SP in UP's state polls earlier this year, a section of her party has been raising a banner of revolt against her, accusing the leader of deviating from Kanshi Ram's principles and compromising the Dalit cause by allying with forces inimical to the so-called 'Bahujan Samaj'. These rebels, who have been campaigning heavily in UP and other parts of the country, threatening Mayawati's overthrow, have made it harder for her to run the party with the heavy hand she'd gotten used to while she was CM of UP. With such turmoil within the BSP, an early election could prove disastrous for her.

Mayawati, unlike Mamata or Mulayam, is also not in the habit of challenging the Central Government's policy decisions. By virtue of this, the BSP can be a more manageable ally for the Congress than the SP. She has also said time and again that she does not want to strengthen the country's communal forces, and such statements are hope enough for the Congress—which, when it comes to the crunch, is given to holding up the prospect of a BJP takeover as its raison d'etre for power.

At the moment, what Mayawati needs most is an improvement of her image among her core voters so that she can counter the campaign mounted by BSP rebels. She has, therefore, been demanding that the Centre quickly clear its proposed Bill for SC/ST promotion quotas in public sector employment. She wanted this done during the Monsoon Session, but her bête noire Mulayam spiked it. Its failure so peeved Mayawati that she labelled the Congress an "anti-Dalit" party, and sought an extension of the session by 10-12 days just to have it enacted.

Later, she demanded that a special session be convened for the purpose. "We have requested the Centre to call a special session of Parliament this month to get this Bill cleared, but before that the Government should ensure that the House will function smoothly," Mayawati told reporters outside Parliament on 7 September.

This is an opportunity for the UPA. A positive signal to Mayawati on the Bill would go a long way in its bid to secure her support, given the political trap the BSP Chief finds herself in. All she may need is a high-profile facesaver.

The fallout of Mamata Banerjee's bombshell goes beyond the Congress' efforts to shore up support from the SP and BSP. The Trinamool's move has set off fissiparous vibes that have hit another ally of the UPA too. The DMK, which has 18 MPs in the Lok Sabha and which is almost as significant as the Trinamool, has also started flexing its muscle. As soon as Banerjee issued her 'historic' threat, the DMK announced that it would support the opposition-sponsored bandh of 20 September. This DMK ploy is an obvious attempt at cashing in on popular anger against the Centre's recent decisions, and perhaps an indication that the party would no longer kowtow to the Centre.

Though the NCP, another major ally of the Congress, is in harmony with the Grand Old Party on these reform measures, its support cannot be taken for granted either. After all, Sharad Pawar has his own political ambitions too.

The Lok Sabha arithmetic permits few certainties.