School for Politicians

A civic leadership incubator programme in Bangalore attempts to teach future political leaders skills of governance.

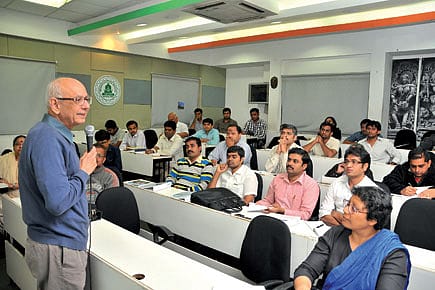

In a tube-lit classroom filled to burst- ing point with about 66 adults across age groups, Mukul Asher, professor of public policy at National University of Singapore is explaining the idea of hidden taxes—taxes citizens pay because of the government's inefficiency or short- sightedness. He argues that bribes paid to government employees are a tax; they are, after all, a payment made to a person who represents the government and are, more or less, compulsory. "Lower income groups are extremely highly taxed," he says, "but the money they pay doesn't go into government coffers."

When he throws the floor open to questions, there are several. Predictably, in keeping with the zeitgeist, there is a question about the Aam Aadmi Party. A student asks if AAP can afford to give away free water and subsidised power to the residents of Delhi. Asher's response is a question. "In the 21st century, what is going to be the commodity that will be the scarcest?" he asks. There is a murmur of responses, then someone gives the right answer: water. "If something is very scarce, would you price it at zero?"

Asher then explains that although a free-water policy may appear to benefit households at the outset, it would eventually hurt them. As water becomes scarcer, the cost of supplying it will increase. Therefore the only way the Delhi government can afford to give its citizens water free is by finding an alternative source of revenue—it can either take money away from other infrastructure projects, or raise water prices for commercial establishments.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The first idea is obviously a nonstarter. And if the government opts for the second, it would increase the cost of doing business in Delhi, forcing commercial establishments to move to other cities. Such an exodus would come back to hurt households, because they are customers and employees of these businesses.

Further, Asher argues, at zero price, no one would invest in increasing the water supply to Delhi. Also, when something is given away free, there is no incentive not to waste it. Users tend to become profligate. "Look at Punjab," Asher says, "A huge amount of water is used in farms because water is free."

This analysis of AAP's free-water policy makes one thing clear to all students in the classroom—public policies cannot be viewed in isolation. They trigger a complex web of consequences, all of which need to be considered by the legislators who make them. A policy cannot be made by grandstanding and playing to the crowd; it requires painstaking, hard- nosed analysis, with inputs from economists, urban planners and other professionals. As Asher tells the class, "It doesn't create headlines."

The lesson is a crucial one for the students, all of whom are attending a Civic Leadership Incubator Program (BCLIP), created by the Bangalore Political Action Committee (BPAC) in partnership with the public policy think-tank Takshashila Institution. The programme aims to groom candidates for corporator positions in Bangalore's 2015 municipal elections. As many as 62 per cent of the students come from political parties, and most of them intend to stand for elections. The rest do not have any experience in politics, but are here because they have a strong desire to improve governance and have already begun doing what they can.

The idea of BCLIP was first floated by TV Mohandas Pai, previously a member of the Board of Directors at Infosys and a member of the BPAC. BCLIP was to be an answer to the obvious lack of administrative skills among Indian politicians. "Bangalore is performing under its capabilities, economically and on other dimensions, primarily because the government is not playing an enabling role," says Sridhar Pabbisetty, a member of the BPAC. Pabbisetty who was previously chief operating officer at Bangalore's Centre for Public Policy, contested the 2013 Karnataka Assembly elections from the Hebbal constituency.

The syllabus for BCLIP is eclectic. On one hand, students learn the basics of economics, finance and urban planning so that they can be efficient administrators. On the other, they learn strategies to break into Indian politics and contest against strongly entrenched, dynastic political candidates with deep pockets.

On a Saturday morning, the day after the session on hidden taxes, the lesson gets even more technical. The 60-odd students, who come from a wide range of educational and cultural backgrounds, are now grappling with the nuances of accounting. Asher is explaining to them the crucial difference between cash-based accounting and accrual-based accounting.

It turns out that most government organisations in India, whether the Indian Railways or the Bangalore Municipal Corporation, still follow the problematic method of cash-based accounting. This means that these organisations have no idea what their assets are, because cash- based accounting does not allow for the preparation of a balance sheet. The problem with such an information gap is that these assets can be potential money-spinners for these organisations.

"At the ward level, it is particularly important to know what assets one has," says Asher. For example, a city like Bangalore could ask commercial establishments to set up shops over bus stations and earn much-needed revenue from this. Or it could put up eco-friendly lights and generate revenue under the Kyoto Protocol. "All well managed cities do this. And poorly managed cities don't," says Asher, talking about such small-scale but effective interventions to improve urban governance.

In all, BCLIP is a nine-month course, the first three of which consist of classroom sessions from public policy experts such as Mukul Asher, bureaucrats like retired additional chief secretary to Government of Karnataka K Jairaj, and politicans such as Pabbisetty. Most political leaders who will address students have a strong record of trying to shape public policy.

For example, Ashwin Mahesh, a climate- scientist who contested the Karnataka Legislative Assembly polls in 2013, is involved in several urban-development projects for traffic management, lake development, etcetera. Rajeev Gowda, a professor of economics at Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, and a Congress spokesperson in Karnataka, has helped kick-start a string on civic initiatives such as Bangalore Needs You.

But politics cannot be taught in the classroom alone. So, as part of the programme, students have had to walk through their respective municipal wards, meeting residents and officials in charge of public services. Next, they have surveyed the status of these services— roads, water, drainage, garbage management and electricity—to find the biggest pain points. By the end of the first three months, each student must develop a ward action plan to solve these problems.

Those with feasible ward action plans will receive Rs 60,000 each from the BPAC to implement them. "It is a very intense endeavour. The budget of it is about a crore, because we want to train 100 people," says Pabbisetty.

A crucial part of the training also involves strategies for campaigning against established political parties. One such strategy is what Pabbisetty calls a 'guerilla campaign'—a low-cost, unconventional drive to connect with voters, which can give traditional large-scale campaigns a run for their money. "What did AAP manage in Delhi? It was a guerilla campaign. We have a whole range of interventions like this. This is to say politics is out there and not necessarily how your party is imagining it today," he explains. In 2013, when Pabbisetty contested the Karnataka Assembly polls from Hebbal he managed to snatch away about 5.5 per cent of the votes after a 37- day campaign.

By spending about Rs 5 lakh, Pabbisetty says he received more votes that the Karnataka Janata Paksha candidate in Hebbal, who had about 200 people walking behind him every day for almost 20 days. "It is about communicating the right issues and touching the voter where [his/her] pain point is."

A few weeks after the session with Asher, students receive a lesson on how important good planning is for infrastructure projects. They are on a field trip to the construction site of Bangalore's CNR Rao underpass. This project, which was sanctioned in 2008 to ease traffic congestion, was scheduled for completion in ten months. Today, five years down the line, it is still incomplete.

Students learn that things went wrong at the planning stage itself. Planners did not take into account the fact that several public utilities, such as optical fibre cables for internet connectivity to the neighbouring Indian Institute of Science, lay under the construction site. Plus, land had to be acquired from neighbouring institutions, and this wasn't foreseen by the planners either. Even without all these problems, there were genuine engineering challenges to be surmounted—the CNR Rao underpass is the first of its kind in Bangalore, because it does not have a central beam supporting its broad archway.

To tie together the interests of so many stakeholders while solving unprecedented engineering problems takes political imagination, says Pavan Srinath, a policy researcher from Takshashila Institution and a BCLIP instructor. "It is the task of a politician to provide the right incentives to each of them and pursue the larger public purpose. Our aim is to teach students to think in terms of interests and incentives."

The course has been an eye-opener for the motley mix attending it. Manjesh Jalahalli Cheluvamurthy, a 35-year-old resident of Vidyaranyapura in Bangalore and a member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, is one of them. Manjesh, who is an electronics engineer by profession, is bothered by the sharp contrast between the infrastructure and quality of life in India and in developed countries he's had a chance to visit. "I want to see the infrastructure improve in our city, because that is the first question I get asked whenever I travel to Taiwan or elsewhere. So, I asked myself: can I bring about some change?" BCLIP has given him an opportunity to tackle this problem systematically. "The syllabus has been outstanding," he says. As part of the ward walkthrough exercise, he has identified road connectivity as the biggest problem in his ward. "I am working on understanding why we are not able to widen these roads. It is mainly a lack of will and lack of dialogue between elected representatives. Also, there is the issue of who gets credit for the work," he explains.

Manjesh is hoping to run for the 2015 elections as a BJP candidate, but if that doesn't work out, "I will look at other party options," he says.

Fifty-nine-year-old Gayathri Sen's ambitions were far less political when she joined BCLIP. "When I went for the interview, I had no intention of standing for elections," she says. "I thought [that] by getting training from here, I [would] be able to do some type of social work." Gayathri comes from a family of academics and is herself in charge of libraries at PES Institute of Technology in Bangalore. "Coming from an academic background, we always feel that we should keep away from politics; that it isn't clean," she says.

But her involvement in civic issues slowly changed her mind. She has been fighting a case, together with other neighbourhood residents, against a neighbour who was attempting an illegal construction.Apart from this, she also works with an NGO that digitises books for blind people. "I have realised in the past few years that unless you get into the system, you cannot change it," she says.

When I ask Pabbisetty how much of a difference such training can make to politics, considering that most governance failures seem to occur not because of a lack of training but of integrity, he says this is only one of several interventions. "But if we don't even try this, we will lose the opportunity to make any change through this process."

According to him, the idea is to make politics an attractive career option for young and competent people. "You and I should equally aspire to be politicians. If we let go of that, we will be governed by inferiors. There is nothing wrong with being governed by inferiors," he says, "just that we will be governed inferiorly."