India’s Own Jasmin Revolution

It took a suicide and the Facebook account of a man named Jasmin to set it off. Within five months, it saw 164,000 nurses rallying online—thousands of them in actual hospitals too—for better work conditions

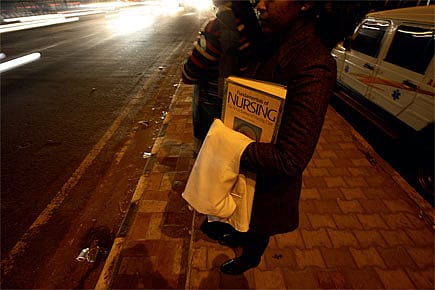

On the morning of 10 October 2011, Beena Baby, a 22-year-old staff nurse at Asian Heart Hospital, Mumbai, was found hanging in her flat in the suburb of Santa Cruz, a flat that she shared with eight other nurses. Beena's monthly salary had been Rs 7,000, half of which she spent on food and her share of the rent. Till that grim morning, hers had been a story of hope—of a self-determined escape from poverty.

Beena's parents had been daily labourers, unable to support their daughter's education. And yet, Beena, who scored 90 per cent marks in high school, managed to get a BSc degree in nursing with the support of an education loan. She was offered a job with Asian Heart Hospital by a recruitment agent who promised her Rs 15,000 a month. It was only on joining that she realised that she'd be paid less than half that sum, and that too for working 14-16 hours a day. On such meagre wages, she could neither support her family nor repay the education loan. According to TP John, Beena's uncle, she decided to quit the job and look for a better one. But she'd had to sign a bond before joining, he alleges, and the hospital demanded Rs 50,000 to release her educational certificates, which it had kept. Beena didn't have the money. It was this last straw that broke her spirit.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The nurse's suicide, it was clear from the start, would not be just another statistic. Her colleagues at Asian Heart Hospital went on strike against being held hostage to bonds they'd been forced to sign. This was around the time that Beena's death caught the attention of Jasmin Sha, a 29-year-old male nurse who had returned home to Kerala after a job stint with a hospital in Qatar. Troubled by the suicide, he called a get-together of nurses—batchmates, friends and acquaintances— in Thrissur, and made his anger and anguish loud and clear. This was 12 October, just two days after Beena's body had been found hanging in Mumbai. None of the nurses present knew Beena personally, but they were all equally upset.

The gathering also had other nurses calling in to express their solidarity. But it was one call from a nurse at a private hospital in Hyderabad that startled them. It was a distress call. The nurse said that she was close to doing what Beena had done. She too was in a debt trap, unable to pay back even a single instalment of the Rs 10 lakh she now owed (including interest), having taken a loan for a three- year BSc Nursing course.

A few days later, Jasmin and a few friends set off to Kottayam, the indebted nurse's native place, to visit the manager of the Canara Bank branch from which she had taken the loan. They planned to raise money and repay a portion of the debt, thus buying her some breathing space. The manager opened a file and showed them the status of education loans availed by nursing students. "There were 46 students in exactly the same dire situation," says Jasmin. Stunned by this figure, they took the phone numbers of all 46 nurses and contacted them. Many had given up nursing for 'better jobs'. Many of the men, for example, had taken to manual labour, rubber tapping and driving autorickshaws. It was mostly the women nurses, with far fewer job options, who were in distress.

Determined to help, Jasmin started a Facebook community. That is how the United Nurses Association (UNA) came into being. The response was astonishing. In three days, its membership went up to 2,000. Jasmin and his friends registered the association on 16 November, and organised a meeting the next day in Thrissur that was attended by 136 nurses, some of whom took charge as office bearers. Sudeep Krishnan, one of those who had quit nursing to become a rubber tapper, took on the role of UNA's general secretary.

Their first agitation was against The Mother Hospital in Thrissur, which had 400 staffers. The UNA formed a unit within the hospital. At first, this 'unionism' was met with a swift and brutal reprisal; 21 nurses were kicked out within a week. "They thought the UNA is only a paper tiger," says Jasmin, "A doctor who represents the management challenged us to prove our strength. We did it by issuing a 24-hour strike notice." Their demands included a revision of minimum wages, limitation of work shifts to eight hours, termination of the bond system, and health insurance for nurses. Apart from the few attending to emergency cases, all of them took part. And within three hours, the management called in the UNA leaders and conceded their demands. All those sacked were reinstated without any strings attached.

As word of this success spread, UNA units started coming up all over Kerala, and soon about 100 hospitals had a wing of the association. They faced resistance, of course. Private hospital managements began using a variety of tactics, throwing nurses out, while trying to alternately bribe and browbeat UNA ringleaders.

Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, for example, the medical college and specialty hospital set up in Kochi by the godwoman Mata Amritanandamayi, sacked the local UNA president N Sreekumar and transferred two office bearers to Mysore within 24 hours of the union taking shape on its premises. When top UNA leaders protested, they were called for a discussion. On 5 December, six of them including Jasmin and Sudeep Krishnan arrived at the hospital. In Jasmin's words, "We were cordially welcomed by an employee of the HR department. We followed him inside. He entered a corridor and disappeared. A group of people in saffron dhotis suddenly emerged from behind and attacked us brutally. They had weapons and were shouting that they would kill us. My left arm was broken. Our state committee member Bibu Poulose's right knee was shattered to pieces. He had to go through multiple surgeries." The police registered a case and the investigation is still underway. On their part, the hospital authorities deny any role in the attack. "Some goons from outside may have done it," says Sasi Kalariyal, Amrita's public relations officer.

As Amrita discovered, however, the hospital's staff were not ready to shrug and move on. As many as 1,300 of its nurses went on strike, and it had to suspend operations. "The ICU and CCU functions were not interrupted," says Krishnan, "We were careful about that." The hospital management, which had initially refused all negotiation and even tried using Amritanandamayi devotees as nurses, yielded on the strike's third day and agreed to implement the demands within three months.

It set off a chain reaction. Over the next few days, nurses at Little Flower Eye Hospital in Angamali, Elite Hospital in Thrissur, and Sanker's Hospital in Kollam went on strike. All of them endured reprisals. At Sanker's, a 25-year-old nurse who was seven months pregnant, Ashwathy, was even manhandled. But here too, the management had to accede to their demands after a five-day deadlock. "They are still trying their level best to harass us," says a UNA leader at Sanker's, "We have been given accommodation at a subsidised rate. Now they are planning to lift the subsidy."

Little Flower Eye Hospital, under the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, deployed a 'religious' strategy to break up their unity; it warned darkly of 'outsiders' out to jeopardise the interests of the Catholic Church. Nuns and priests went on a march against the errant nurses.

The Indian Nursing Council, an autonomous body under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, places India's nurse count at 1.8 million. By one estimate, about two-thirds of them happen to be Malayalee, working in various parts of the country. There are also unregistered nurses, usually designated as nursing assistants, who hold diplomas instead of degrees in the discipline.

Salaries for nurses vary widely. In most private hospitals in Kerala, a large number are paid as little as Rs 2,500 per month. Most are overworked, with their duty-time stretching to 16 hours in a majority of cases. And for all their hard work, they are treated poorly. If they have access to a staff canteen, it is often separate from that of doctors and with distinctly lower-quality food served. Most appalling, however, is the bondage they are wrapped in by the legal-looking documents they are typically made to sign when they join. Under these work contracts, they must pay sums of up to Rs 2 lakh to buy their freedom if they opt to leave before a pre-set period of time (often a few years). "We are forced to go through this suffering. When it crosses all limits, we may do what Beena Baby did," says Santhi, a staff nurse at a private hospital in Ernakulam.

Most nurses are women, but they rarely get such benefits as maternity leave. According to the UNA, pregnant nurses are made to resign, and if they rejoin, it is often at a junior level—with no consideration for their work experience. Another major problem is sexual harassment. "A doctor used to call me to his room at least ten times a day for no reason," says a nurse at a multi-specialty hospital in Ernakulam who quit in frustration, "At first, I tried to avoid it. I did not want a direct confrontation with him. Finally, I had to burst out at him. Life became hell after that. He started finding fault with me for anything and everything. I had no option but to quit." She has left nursing altogether.

In Kerala, the UNA's struggle has become something of a mass movement. As Jasmin claims, "All political parties, trade unions and social organisations in Kerala support us." The association has issued notices to around 100 hospitals in the state, asking among other things for minimum wages as fixed by the Government (around Rs 15,000 per month), termination of the bond system, eight-hour duty, health insurance, risk allowances, and freedom from exploitation at work. Hospital managements have had to sit up and listen.

There has been unrest among nurses in other parts of India as well. In 2010, nurses across seven hospitals in Delhi went on strike, demanding a better deal. Hospital managements retaliated with mass terminations, seizures of certificates, and even physical assaults. Little wonder that the UNA has found support in Kolkata, Mumbai and Mysore, among other cities, as well. On 24 January, representatives from Hyderabad, Mysore, Delhi and Mumbai participated in a Strike Declaration Convention in Ernakulam. The association now has units in 436 hospitals and 164,000 members. Units have been formed in Qatar, Oman and Saudi Arabia, apart from the UK, Netherlands, Ireland and Israel.

Just as the Arab Spring began with a suicide by a fruit-and-flower vendor who immolated himself in protest against the authorities in Tunisia (whose national flower is Jasmine), its flames of rebellion fanned by Facebook, India's nurse uprising began with a suicide and an online community started by a man with what is now an evocative name, Jasmin.

The young revolutionary knows he no longer has the option of returning to Qatar for work—his visa has expired. But he has far more important things to do in India. Such as teaching hospital managements a thing or two about fair working conditions for nurses, now that they are all ears for a change.