Dread and Belonging in Kerala’s Party Villages

The state's Kannur district is riddled with villages that are dominated by a single political party. A closer look at this peculiar phenomenon

CN Pradeepan, a farmer in Kerala's Kannur district, is always looking over his shoulder. Most people in Kannur support the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPM), but Pradeepan owes his allegiance to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). He has been an active member of the party for 20 years, and is now its Panchayat Committee President in Thillankeri village. Being in the political minority here has its hazards. And so he is always on his guard. "Many of them are my friends, some are even close friends," Pradeepan says of the CPM folk in his village, "But in my heart of hearts, I don't trust them. I have not been threatened or attacked so far, but I am always alert. In bad times, I am sure friends will turn foes." He did not have an office in which to meet me. Once, he did. But some six years ago, it was wrecked by alleged CPM goons. Neither did he want to take a chance by meeting a journalist in public. We held our conversation in a car.

Pradeepan's is not an isolated case. Nor are BJP men always the ones under pressure. In a district riddled with 'party villages'—where almost all residents are loyal to a single party—fears such as his are common to all those who dare work for 'the enemy'.

That 'party villages' exist in Kerala cannot be denied. Used loosely, this term refers not just to clusters of huts but sometimes even larger areas of 200-300 families. But that's not why the term is controversial. Across the state, party villages are seen as terrifying places to live in or visit.

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

The CPM, which has many such villages, officially denies their existence. To this party, the term is just another creation of the right-wing media's agenda. The notion that it has an iron grip of entire villages, the CPM fears, tarnishes its image. What it has, of course, are villages with a 'strong support base'.

If the CPM sounds defensive, it is partly because it lost power in Kerala last year to the United Democratic Front (UDF), a Congress-led alliance. What has brought the issue into focus, however, is the killing on 4 May of TP Chandrasekharan, a CPM rebel who had just quit the party to set up the breakaway Revolutionary Marxist Party. With a gang of goons of a CPM village the prime suspects in this case, the UDF's home minister declared that the government would "evacuate and liberate" party villages. The minister's implication, clearly, was that these were being held by force against their will.

Party villages spell bad news in the media these days. But that does not stop workers of the Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), a member of the ruling alliance, from making proud claims of having party villages of their own—modelled on the CPM's—in their north Kerala bastions. The BJP, on its part, also denies having any party villages; it is the CPM, it says, that plays this game. Local journalists, however, refuse to buy any of these denials. Any stranger visiting Kannur, they caution, will have his intentions questioned, and if you get too nosey, you could be manhandled or worse. Some of this is true. Some of it is false. It is not easy to separate myth from fact around here. The police only have statistics to offer that are hard to verify. According to police sources, Kannur has about 50 party villages—more than 20 of them under the CPM's sway.

Kannur has a long history of political unrest and violence. Its bloodiest phases were marked first by a fight against British rule and then a peasant movement against feudal lords that was later led by Communists. Their goals may have been lofty, but these struggles lent legitimacy to the use of violence—or 'resistance' as the CPM likes to call it—as a political tool.

Till a few years ago, the CPM's main enemy was the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the saffron entity that backs the BJP. Now, the Muslim League is its main opponent in many villages. But the battles have mostly been between the CPM and the RSS-BJP. The CPM counts 160 of its dead as communist martyrs among the 250 odd killed in political violence in Kannur over the past four decades. The RSS-BJP claim to have 78 balidaanis (martyrs) on their own roll of honour. The Congress, too, has lost workers to political violence.

In the analysis of a police officer who has worked in the district for many years, sustained bloodshed has led to ghettoisation. "The formation of party villages started in the early 1960s," he says, "A series of bloody clashes between the Congress and the CPM, and between the RSS and the CPM prompted people to move to safer places, and these ended up as their pocketburoughs."

Assassinations have been common. Few can forget the gruesome case of the BJP's KT Jayakrishnan, a school teacher who was slaughtered in a classroom in December 1999. It was done with such brutality that his terrified students were sprinkled with blood. By local accounts, it was retaliation by the CPM to an attack a few months earlier on P Jayarajan, the party's district secretary, who survived 17 knife wounds. Among other brazen attacks, KV Sudheesh of the Students Federation of India (the CPM's students wing) was hacked to death in 1994 in front of his parents by RSS thugs (who have since been convicted of it).

Tension is palpable in other ways too. Party villages often bear signs that look like victory symbols of an occupying force. If you see electric posts, bus shelters and public wells all painted red, assume that you are in a CPM village. Huge hammer-and-sickle props greet you at every turn. There are also hoardings of 'martyrs', usually in the company of luminaries like Che Guevara. You might also spot signposts saying 'Welcome to the Communist village'. So while the party denies their existence, rural reality has a different story to tell.

The electric posts, bus shelters and public wells turn saffron when you enter an RSS village. Welcome boards and other hoardings here have pictures of balidaanis instead.

While the CPM and RSS have vied for control of villages since the late 1960s, the IUML has got into the act only recently. But it is keen to make up for lost time, by the look of its party villages. These too have a giveaway appearance. Their welcome signboards, for example, often say 'Shihab Thangal Nagar'—in honour of the party's late president Syed Mohemed Ali Shihab Thangal.

Like the CPM and RSS, the IUML has also adopted thuggish tactics in recent times. In a cycle of clashes between the IUML and CPM in Pattuvam Panchayat over two years, each side tried to defeat the other by brute force. It came to a brief halt only after the murder of Abdul Shukkoor, a 22-year-old IUML worker, this February.

Equally common to all these villages is the contempt in which rival parties are held. But in public forums, all three parties profess a respect for democracy and differences. "We have a strong base in many panchayats in Kannur," says P Jayarajan, the Kannur district secretary of the CPM, "We do not stop any other political party from working by force."

On the face of it, that's not a lie. Party villages do have token opposition residents. In the CPM's Peralassery Gram Panchayat, Congressman T Sureshan—the party's only such ward member—is held up as evidence of that claim. Of the village's 18 wards, the CPM holds 16, and the IUML, one. Sureshan, a door-to-door milkman, won his seat not by campaigning against the CPM, but on account of people's familiarity with him. He is free, he says, to hold gatherings and political meetings in peace. He takes care, however, not to make a speech that may annoy the CPM.

"Peace prevails when we offer no resistance. In fact, the CPM needs people like Sureshan and me for a token display of their tolerance and magnanimity," says K Pradeep Kumar, a Congress worker in Chokli Panchayat, a CPM village with a record of violence. The CPM here has red lines that must not be crossed, Kumar says, and violence erupts if anyone dares to. Making speeches is a no-no, for example, and he does not risk them.

There is a price to pay for evoking the CPM's wrath. K Hareendranath, a teacher who is the Congress' Mandal committee secretary in Chokli, learnt this the hard way when he tried to challenge a "bogus vote" polled by CPM in a 2010 local election. "They tried to poll the vote of a student of mine who was abroad at the time," he says. About a week later, on his way back from a nearby temple, he was attacked by goons. "They stabbed and left me badly injured," he says, "My wife was with me. She tried to stop them, but she too got hurt." The case is still under investigation.

The lives of token opposition leaders in RSS and IUML villages are not any easier. And while the cadreless Congress has no villages under it, it is not above the use of violence. Most of the CPM's comrades lost in Kannur have been to violence sparked by the Congress, whisper party sources.

Yet, the champ at booth capturing, the main point of village domination, in Kannur remains the CPM. So say observers. The party gets into the act well in advance. Voter lists are packed with as many names as possible, including non-residents and the dead, and then it's for party cadres to ensure that all these votes are cast, even as election officials look the other way. "Any voice of dissent could end up in violence, so we keep quiet," says a Congress worker who has been a booth agent in the CPM-held Panoor village, "I have helplessly watched CPM people cast multiple votes many times."

In these parts, quip Kannur locals, polling percentages often go as high as 110 per cent. Bogus voting is on the decline, though, claims an Election Commission officer in Kerala: "The introduction of electronic voting machines has made it difficult."

The Malayalam media too has had a role in the making and unmaking of party villages. It is their favourite subject of coverage. Serialised reports on such villages appear both in print and on TV. These are usually 'scandal stories' with scant respect for facts.

Take the recent controversy over the newly-built house of Pinarayi Vijayan, the CPM's state secretary. The stink first arose when two party members from Onchiyum Panchayat in Kozhikode district were suspended for allegedly visiting Vijayan's house in his village Pinarayi in Kannur. They had reportedly visited the house to verify an allegation that Vijayan had built a Rs 3 crore mansion and, thus, flouted the party's code of conduct. At the time, the air was rife with rumours of this 'mansion'. There was even a picture of a huge house doing the rounds online. Vijayan complained to the police, and their cyber cell arrested a person who they said had created the image by morphing a picture of an NRI's house in Thrissur. But even that didn't end the matter. Oddly enough, few in the media took the trouble to send a photographer to Vijayan's house—which, while large, is no mansion. "If we publish such a photograph," admits a senior journalist at a leading Malayalam daily, "the controversy will come to a close, which we don't want."

Few districts in India are as bitterly divided by party politics as Kannur. Violence often does serve the cynical political purpose of keeping control of electoral outcomes, but there are some signs that people here are fed up of violence. This offers hope that the spectre of party villages will fade away in the years ahead.

Till the end of the 1990s, the making of crude bombs was said to be a 'cottage industry' in the party villages of Kannur. Not anymore. E Saneesh, a former CPM activist and now news editor of India Vision, a Malayalam news channel, says that things nowadays are not so bad. "On my trips home [to a party village], when I would meet youngsters I knew, some of them would have their hands constantly in their trouser pockets," he says, "They had lost their hands [in accidents] making crude bombs. Over the last ten years, the new generation has lost interest in such activity."

The animosity between the CPM and the RSS is also on a downtrend, though this may be because the latter has been losing influence over the past decade. The BJP has no single seat in the Kerala Assembly, and has hardly been able to win new recruits in the state. "Marriages now take place between CPM and BJP families," says K Ranjith, the BJP's Kannur district president, "This was beyond imagination a few years ago." Adds a local BJP leader, "For us, this is a losing cause. For the CPM, every martyr is a gain—they campaign and gain more votes on martyrdom. But for us, the death of a worker is just a loss to the party."

Political eliminations still take place, but they are now carried out by professional killers. "All parties have their own killer gangs," says a local CPM leader in Kannur. He is sick of it, he says.

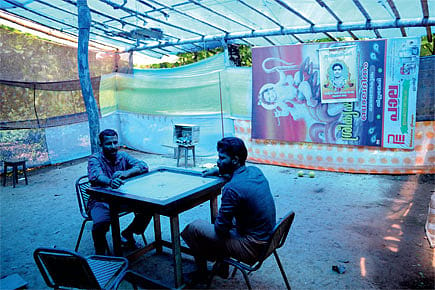

The only ones who benefit are killer gangs. It was hired assassins who killed Chandrasekharan, say the police. NK Sunil Kumar alias Kodi Suni, the gangster boss accused of leading the attack, lives in a grand two-storey house in Chokli, a CPM village, that his declared sources of income probably cannot justify. Our visit to Kodi Suni's house was a tense experience. The driver was interrogated thrice by different people. The photographer kept his camera in its carrybag. He did not want to take a chance. Suni's sister, who was home, was reluctant to talk to us at first, but agreed after some persuasion. While talking to her, we realised that we had been under surveillance. We were being watched by shadowy figures posted atop nearby constructions. She got three calls enquiring whether we had left or not.

Chokli being a party village, an intruder would attract glowers anyway, but the context of our visit was highly charged. With the UDF tightening screws on villages held 'hostage' by political parties, and the CPM facing the heat for its rebel leader's murder, this was an opportune moment for the UDF's 'liberators' to strike. There was unease all around.

Across Kannur, many people we met did not want to be photographed. They did not even want to disclose their names. They had little confidence in their freedom of speech. That their villages were not really theirs was largely why.

But then, the phenomenon of party villages can be deceptive. If there are claims of duress, there are also signs that villagers join hands in support of a single party of their own volition. No single narrative explains it. All that can be said for sure is that party villages cannot be wished away by UDF 'liberators'.