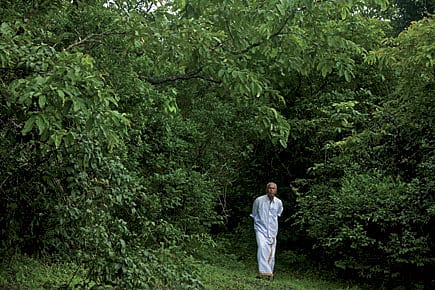

Abdul Kareem: At Home in the Woods

The first phone call you make to him begins with a volley of questions: Where are you from? Where in Bombay? Near there? Near here? Call me after you come to Kerala.

You tell him when you are arriving in Kerala. He says call once you are there. You call. He says he is going to be travelling. He can only meet you next week. You tell him you have to return before that. Just as abruptly he says, "Okay, then Friday after 4 but call first on Thursday." You are sceptical now—if he was really going to be out of town, how can he meet you, and if he was not going, why did he say so? Your instinct begins to hint you are headed in the direction of that grave where all stories that didn't work out are consigned. You are wrong. On Thursday, as soon as he picks up the phone, he says come.

Later, during the course of the interview, you learn that the instincts were not really that off the mark. This is towards the end when Abdul Kareem is speaking about the first time he got written about. In 1998, a journalist from a national magazine had heard about a man who built a forest and had called up asking if he could come over the next day. Kareem lied to him that he was going to be out, from 8 in the morning in fact. On being asked when he would be back, he said it would be after two days. "I don't like these things," he tells me. "Didn't I discourage you too?"

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Well, somewhat, but it doesn't really seem to work. I am here. So was that journalist who landed at 7 o'clock the next morning and got the article out that began Abdul Kareem's makeover.

His forest is near a village called Parappa, about 30-odd kilometres from Nileshwar, a town abutting the sea. It is monsoon and that is perhaps the wrong season to come if you want to admire Kareem's feat. The state is green end to end and his forest is just another patch. In summer, it is a different story. From Nileshwar, drive inwards away from the coast, roll over a few hills carpeted with rubber trees and stop by to ask a few people who answer with 'Kaadu Kareem?' or 'Forest Kareem?' until off the road, you see a well laid mud path disappear into woods. There is an outhouse of sorts just at the beginning of the path. Deeper inside, about 50 metres, is his residence. We go there and are directed to the outhouse. Kareem opens the door, speaks in grunts, takes me into a room inside, opens his computer and starts sending emails to me. They include his CV, media reports and links to documentaries. This, I am told, is so that I know the entire story. I try to tell him that this is not how interviews go, we must speak. He says yes, of course, we will speak, and sends me more emails. I get questions in edgewise.

How did it begin? Of course, of course, I'll tell you but let me just finish sending this mail. Amitabh Bachchan gave me an award in 1998.

What was this place like? I'll tell you but just let this mail go. Shekhar Kapur has written about me.

Eventually, as my phone keeps pinging with the mails that I am getting from the man seated next to me, we get the shadow of a conversation going and he talks about creating a forest.

Where we are sitting is a 32-acre property with thousands of trees, dense and wild and varied enough to qualify for a forest. This is land he began to accumulate in 1977. Till then Kareem's journey in life had very little to do with nature. He had finished school and then dropped out after his Plus Two (class 12) to head to Mumbai for work. After working in a dockyard for a while, he became a travel agent. The Middle East oil boom was beginning and he capitalised on it, organising visas and ticketing, shuttling between Dubai and Mumbai. He made a lot of money.

Kareem says he wanted a place to relax in between his travels and that was how in 1977 he bought five acres here for a grand total of Rs 3,750. The land was made up of laterite rocks, nothing grew on it, there was no water and no one lived here except for Tribals. The first year Kareem planted saplings, and all of them except one withered and died. The next year he planted even more saplings. There was a forest 10 kilometres away and those were the species he planted. He was also a little careful in giving them water around the hot summer months this time. Not too much, just a little because they were the local variety of trees and didn't need to be constantly irrigated like, say, palm trees or paddy. And this time, they started to grow. He bought more land. "Those days you got it for the price you asked for. There was no one here. No birds, no trees. I dug a pond. No water," he says.

But there was a sign of how things were changing with the trees growing. There was a well that would be empty in the summers. "By 1981, I saw that with the trees growing, the water in the well was also rising. And it wouldn't go dry in the summers," he says. What the trees were doing was reining in the waters during the monsoon and raising the water table below. He says, "There is a lot to learn in this—how can water be produced by a forest, how can climate be controlled by a forest, how can water be purified by a forest. We have many ponds here now."

Some of the initial problems were to do with Tribals coming and helping themselves to the young trees. When he asked them to stop, they would say that they needed the wood to buy food. There was a store started by one of his workers nearby and Kareem kept two sacks of rice there. Whenever Tribals came for wood, they were given the rice instead and told to leave the budding forest alone. "Later they realised that the responsibility for protecting it was also with them because they were getting water from here," he says. And that was because the land was becoming suffused with water. There were wells and ponds which never dried up and these supplied drinking water to those living around. "In the beginning, the locals thought I had no work but to plant trees on rocks. After 10 years, they were convinced. Have you seen my water? It has been 17 years since I kept water in a bottle. It is still pure," he says.

Kareem decided to settle full time here in the mid-1980s and started a business trading in cashew nuts. The land itself, while its value was growing, didn't give him any income. By the mid-1990s, his business wasn't doing too well and he had daughters to marry off. It was in such worrisome circumstances that his story became public. Soon after the first media report, he was called by the company Sahara to its Amby Valley project for an environment award. Then the story just kept getting traction. Now, Kareem's forest has thousands of people, including researchers and school children, coming to visit. He was given a petrol pump for his contribution to nature conservation and regularly gets awards and accolades.

You walk on the mud path with him and he points to a bald patch with a shaving of grass on it and says this is how the entire property was like. You look around and see a wall of trees where once there was open air. At the top of one of them, silhouetted in black against the sun, is a bird with a long tail—a black-tailed drongo. The birds also came when the trees came and that led to more trees that he didn't plant. "There are many trees with wild fruits. Birds will come to eat them, they will bring in new seeds. They will grow. There are 700 varieties of trees, flowers and medicinal plants," he says. He picks up what looks like a wild berry and says that the seed inside, when powdered and put into tea, is useful for people with heart conditions. Migratory birds also stop here. "Now hornbills come, lay eggs and go when the eggs hatch. Rarely, we also have green pigeons," he says. Wild hens, peacocks, wild boar, monkeys, snakes, jackals—Kareem's forest has all of these.

The property's price would probably go into tens of crores. He is 69 now and his children are all settled in the Middle East. He has a strategy to ensure that they don't sell it or cut the trees after him. "This year, in about 1,000 trees, I have put pepper [vines]. If it works, then my children will protect it because they will earn from it. They will not cut the trees. If they cut [one] they will only get the value of the tree, but pepper will grow and every year they will earn from each plant," he says.