The Last Remains of Khilafat

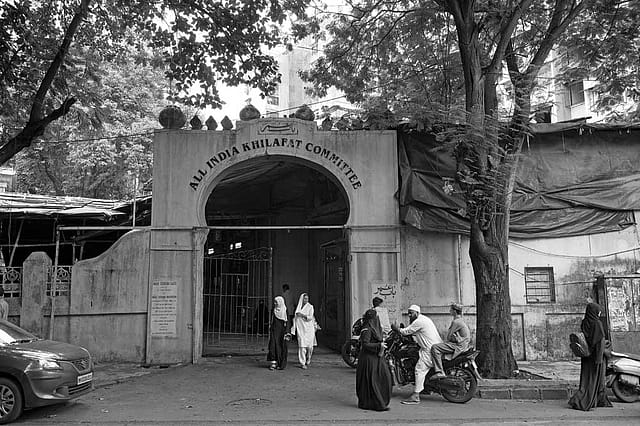

IF YOU walk down the street, for obscure reasons called Love Lane now, it would be easy to miss the place. You need to look up for an entrance arch with the words painted on top—'All India Khilafat Committee'. Because it has been raining in Mumbai the central courtyard is now an artwork of wooden scaffolding on top of which a massive blue tarpaulin extends through the entire length. To the left is a hall in which a man tells students seated on neat rows the definition of syllables and consonants. It is an education college and they are learning to be teachers themselves. Behind them on the wall are photographs that go back a hundred years. Not all of them have captions. One that does, says: 'Ali Brothers and their Mother'. Two stately bearded men dressed in black sherwanis and topis sit on the floor, either side of a woman in a white abaya. A little ahead, there is another image of both these men in prison gear, white shorts and half-sleeve tunics. And still later, an image, the photo yellowed with age, of the house as it used to be. The dilapidation is evident because it too shows wooden scaffolding but it is not because of the rain, just the holding back of ruin. Khilafat House was rebuilt later, its fortunes wavering with time, as did that of the protagonists who made up its story, one that intertwined with the creation of India.

The house was central to the Khilafat movement, an agitation that began in 1919 after the end of World War I in which the British emerged victors and Turkey, or the Ottoman Empire, was among the defeated. Since the Ottoman Sultan also held the religious title of Caliph of Islam, there was widespread apprehension among Muslims that the British might dismember the authority. They sought to build pressure on the British to keep the religious role of the Caliphate untouched when the terms of the post-war treaty were being drawn up. Though it began as an issue concerning Indian Muslims, Mahatma Gandhi saw a larger opportunity. He had returned from South Africa in 1915 and was gaining in stature as the primary mass leader of the Congress. In joining forces with the movement, he envisioned the united Hindu-Muslim front that had been eluding him.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

It led to a new generation of leadership. Among Muslims, the Ali brothers— Mohammad Ali Jauhar and Shaukat Ali Jauhar—became figureheads. Gandhi, still more politician than saint but on his way to capturing the soul of India, found in the Khilafat movement the first big spark of that journey.

In the book Gandhi And The Ali Brothers, historian Rakhahari Chatterji writes, 'During the first half of the year 1919, Gandhi was struggling with Rowlatt Satyagraha and major developments like the Jallianwala Bagh massacre that followed from it… it must be admitted that despite Muslim participation, 'in large numbers' in certain places, as an instrument of Hindu-Muslim unity, Rowlatt Satyagraha proved to be inadequate… It cannot, of course, be vouchsafed that but for the Ali brothers, Gandhi would not have taken up the Khilafat cause; yet it is true that despite his ambiguities about the absolute merit of the Khilafat issue or whether Muslim demand would really be met, the Ali brothers' firm commitment to it and the impact of that commitment on the Muslim masses had indeed encouraged him to consider the issue as his own.'

IN THE book, Gandhi in Bombay, Usha Thakkar and Sandhya Mehta also note his interest in drawing Muslims into the nationalist movement through the Khilafat issue: 'He had achieved success uniting Hindus and Muslims in South Africa against racialism and was now very hopeful to achieve Hindu-Muslim unity in India on this issue. He was concerned about the growing frustration among the Muslims over a religious issue and did not want it to erupt as a violent protest. Gandhi and some leaders among both the communities thought that the Hindus and Muslims together could exercise some pressure on the British government. According to him, his sense of moral responsibilities made him take up the Khilafat question.'

During the movement, protest meetings were organised across the country and days were marked to highlight the issue. It later graduated into the Non-Cooperation Movement. 'A second Khilafat conference was held during November 23-24 1919 in Delhi… It was in this conference that Gandhi 'for the first time' used the expression 'non-cooperation' as a strategy to deal with the government. However, despite insistence by extremists like Hasrat Mohani that boycott of British goods should be launched, Gandhi held his ground in opposing this idea, for he believed it would unnecessarily hurt British commercial interests,' writes Chatterji.

It would only be a year later that Gandhi would launch the Non-Cooperation Movement which would then be abruptly called off two years later following the violence in Chauri Chaura. But by then, it had shown the British how tenuous their rule could be in the face of unwilling non-violent subjects who had been mobilised. And Indian freedom fighters realised that independence was a realisable dream.

The Khilafat movement had an unforeseen end and it was not the British who were responsible. In 1924, the new Turkish Republic government under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk abolished the Caliphate. It however didn't lead to the end of the Khilafat Committee in India which continues even to this day. Sarfaraz Arzu, the editor of Hindustan, an Urdu daily newspaper, is the current chairman of the Khilafat Committee. His father, Ghulam Ahmed Khan, also the founder of Hindustan, hailed from the then state of Rampur located in present-day Uttar Pradesh. Rampur was also where the Ali brothers came from. "Since there were many people who had migrated from Rampur to Bombay, the Khilafat Committee also became a hub for their activities," says Arzu. When the Quit India Movement began, the newspaper was banned and Arzu's father would cyclostyle copies from a machine kept in a moving vehicle. Eventually, he was jailed for six months. His father continued to be associated with the Khilafat Committee and, in 1978, when he passed away, Arzu became involved in it.

After Independence, the Khilafat Committee's activities were mainly concerned with organising an annual procession on Eid-e-Milad, the birth date of the Prophet, and with publishing a newspaper called Khilafat. It was brought out from Khilafat House, which was renovated in the early 1980s. "It was an old wooden structure and would have fallen down. A new building was constructed," says Arzu.

The man who brought in a fresh lease of life to the Khilafat Committee was the late Rafiq Zakaria, freedom fighter, politician and Islamic scholar, who was its chairman for many decades until his death in 2005. "Rafiqsaab was instrumental in getting permissions for starting an education college over there. The House was in shambles. He realised the importance of the historical place that Khilafat had in India and started putting things together and revived the whole institution as such. Khilafat had its footprint all over India, Delhi, Lucknow, Calcutta, even in the south, but everywhere else the candle has been extinguished. It was kept alive in Mumbai thanks to Dr Zakaria," says Arzu.

The Eid-e-Milad procession is said to have been started by Gandhi and the Ali brothers as a political statement. "At a time when you didn't get permissions for conducting political meetings and congregations, the Prophet's birthday was something which couldn't have been banned by the British administration at the time. The same way as Ganesh Chaturthi was used as a vehicle by Lokmanya Tilak to take everybody along, the procession on the Prophet's birthday was established. And it continues even today. The idea behind it is to bring all the communities together and ensure that communal harmony and betterment of the fraternity continue. It has been a tradition that amongst those who lead the procession there have been prominent non-Muslims also, like Motilal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. The procession starts from Khilafat House and winds its way through various Muslim localities. The number of participants at any time is around 4 to 5 lakh," says Arzu.

In 2016, they stumbled upon historical documents that gave them a glimpse into how vibrant the movement had been. They had been searching for lease related documents when, in a room that had not been looked into for years, four registers were discovered. The pages contained minutes of meetings that happened there a century before. "We thought that most of the records had been lost, due to dampness in the earlier building or eaten up by termites. But somehow, these survived in a corner. They were registers where you note down minutes of the meetings and very well written, both in English and Urdu," says Arzu.

For instance, it was written on one page that the Khilafat Committee was perturbed about the condition of war-torn areas and decided that they should send in a delegation of doctors, nurses and medicines and monetary help of 50,000 pounds. There were proposals discussed about withdrawing from the army and British services. "And then there were points being raised that if people gave up their vocation, how were they going to survive? There was a counterproposal that anybody who resigned from the government service would be compensated by the Khilafat Committee which would try to provide them regular emoluments and find alternate sources of income. All these things were under discussion then," says Arzu.

He says that the Committee is keen on creating a Hindu-Muslim research centre, an idea that Rafiq Zakaria had first mooted. "He had foreseen that there is a requirement for a centre like that. It is still on the radar and we would like to establish it once we have created enough space for it because the campus as it is today is totally utilised by the education college itself," he says.

Another idea was to have a museum. It was mooted by the government of Turkey after they found the registers. "We had invited the Turkish Consul General in Bombay to show him all the records we had. He was very moved and surprised that Bombay had had such a fine relationship with the Turkish people at that time. So he spoke back to his ministry in Turkey. And they said let us reignite those flames and have some sort of a historical presence here. That is how they proposed a museum dedicated to Indo-Turkish friendship. We had provided them with the basic space and even the designs were in place but the ball lies in the court of the Turkish government," he says.

For present-day India, Arzu says the Khilafat movement can hold a lesson on communal harmony and unity. "It was an all-inclusive and all-pervasive presence across communities and states. There couldn't be any better example of cooperation among Hindus and Muslims, when we had a common enemy, fought against it and succeeded by combined effort. The enemies have just changed. Now we have to be waging war against poverty and backwardness and the same idea should be re-enacted and reinforced. That's how we can move forward," he says.