Abdul Karim: On Her Majesty’s Service

THE SPRAWLING precinct of Kabristan Maszig at Panchkuian in Agra is anything but quiet this morning. Men in white kurta pyjama walk in droves, some sitting by the graves, chanting. Others chatter as they walk past. As we make our way in, a caretaker hobbles towards us, "Not today, sir," he tells Rajiv Saxena, the 63-year-old local journalist who is leading this small pack of visitors. "We're here to see the grave for just a few minutes," says Saxena, "These people are from Delhi." The caretaker's eyes widen with acknowledgment. "For that, definitely, go ahead," he says. A bemused Saxena says, "I'm here a lot, mostly for this one reason. They let me go inside whenever I bring people for this purpose."

We walk into the kabristan, once a Mughal burial ground, trampling overgrown bushes. Somewhere, we lose our way until a worker redirects us to the right route. A mound or two, and several steps later, we are finally at our destination: at a canopied octagonal open chamber, "an exceptional structure for a grave", in Saxena's words, held up by pillars. Inside, there are three graves, the one in the middle bearing a more ornate, marble gravestone. On it is an inscription in Urdu script, which translates to:

This is the last resting place of

Hafiz Mohammed Abdul Karim, CIEVO,

He is now alone in the world

His caste was the highest in Hindustan

None can compare with him

The poet finds it difficult to praise him

There is so much to say

Even Empress Victoria was so pleased with him

She made him her Hindustani ustad

He lived in England for many years

And let the river of his kindness

flow through this land

The poet prays for him

That he finds eternal peace in this resting place

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

"The words on the gravestone are in Farsi. A commoner wouldn't be able to understand what's written or whose grave it is," says Saxena. Despite the eulogy, Abdul Karim is a forgotten footnote in the history of colonial India, much more so in Agra. "Kuchh bachaa nahin hai yahaan (There's nothing left of him here)," Saxena mutters, as we turn around to leave.

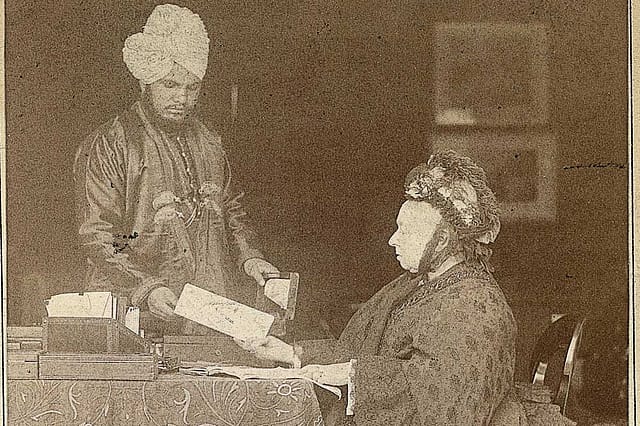

Who was Abdul Karim? To a layman, the name doesn't evoke even the slightest recall. History books do not mention him. In the UK, all that remains of him are mentions in the Queen's Hindustani journals, circulars and gossip in archival media reports, among other scanty sources. At the Durbar Hall of Osborne House in East Cowes, Isle of Wight—designed to highlight Queen Victoria's relationship with and understanding of India—hangs his portrait, a regal picture of a man decked up in all the finery of royalty. This is a story, tucked away in a remote corner of history, of a man who was so close to Queen Victoria that the entire royal household was consumed by jealousy. There was gossip and slander; many drew parallels between him and the Queen's previous personal assistant, John Brown, whose relationship with the Queen is viewed with much speculation even today.

This 24-year-old Muslim Indian man rose from a mere servant to become the Queen's munshi, becoming her closest confidant and driving the royal household up the wall, to the point of hatching conspiracies to get rid of him. His downfall, however, came faster than his meteoric rise—the Queen's death was followed by the destruction of all his personal records, followed by deportation and subsequent death in his hometown, Agra.

Even as a British-American comedy-drama directed by Stephen Frears (of Philomena and The Queen fame), titled Victoria & Abdul, releases in theatres worldwide, inviting the world to look at this speck of colonial history for the first time, the question continues to mystify: who was Abdul Karim?

BORN IN AGRA in 1862 to Sheikh Mohammed Waziruddin, a hospital assistant, Karim was shipped off to London in 1887 at the age of 24 as part of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee celebrations, as one of two Indians—the other being Mohammed Buksh—to serve the royal household. The Queen was immediately taken by Karim, who was 'lighter, tall, and with a fine serious countenance,' writes author Michael Nelson in Queen Victoria and the Discovery of the Riviera. An Indophile, the Queen wanted to learn more about India and immediately chose Karim to teach her Hindustani. 'He proved a hard taskmaster… Karim would write a line in Urdu, followed by a line in English and then a line in Urdu in Roman script. The Queen would copy these out,' writes London- based journalist and author Shrabani Basu in her 2010 memoir, Victoria & Abdul. A few weeks into her classes, the Queen noted in her journal: 'Am learning a few words of Hindustani to speak to my servants. It is [of] great interest to me for both the language and the people. I have naturally never come into real contact before.'

This was the beginning of the Queen's unlikely relationship with Karim. In her Hindustani Diaries, especially, along with her correspondence with him, the Queen's affection for the man is clear. She often signed her letters as 'Your loving mother' or 'Your closest friend'. So important was he to her that when he articulated his desire to go back to India, on account of being unhappy with his 'menial' role as a servant, she wrote to him: 'I shall be sorry to part with you for I like and respect you, but I hope you [will] remain till the end of this year or the beginning of the next that I may be able to learn enough Hindustani from you to speak a little. I shall gladly recommend you for a post in India which could be suitable for you and hope that you may be able to come and see from time to time in England.'

The peak of Karim's career came when, in August, 1888, he was conferred with the title of Munshi Hafiz, becoming the Queen's official Indian clerk. All photographs of Karim waiting at the table were ordered destroyed and a portrait of him was commissioned to Joachim Von Angeli. The Queen held her Urdu lessons dear and mentioned missing them every time Karim would go to India on leave. This was also a time when resentment against the man had set in, not just among other royals and British staffers, but Indians too. The surprise and disdain was visible, especially when Karim began to accompany the Queen on her vacations. In Queen Victoria and the Discovery of the Riviera, Nelson writes about Queen Victoria's holidays to the Riviera and the inclusion of Abdul Karim in her sojourns: 'To the surprise of the Court she soon installed Abdul Karim in John Brown's room at Balmoral. He became even more hated than Brown had been. When Abdul Karim fell ill on one occasion the Queen visited him several times a day and stroked his hand… In 1892 Abdul Karim's name appeared for the first time in the Court Circular list of those accompanying the Queen to the Riviera.' It is also believed that Karim himself took to his new position with much vanity. In one incident on April 26th, 1889, during the staging of The Bells by Emile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrian, Karim took offence when he was made to sit with the rest of the servants. The Queen immediately ordered for the Munshi to be seated with the rest of the royal household.

Karim is also said to have driven the Queen towards Indian politics. 'As he provided her with information about the insecurities of the Muslim minorities, the Queen wrote lengthy letters to the viceroy about the issues Karim raised. She felt her discussions with Karim helped her get a feel of the pulse of Indian affairs, as she was getting the native's view of the British administration and its effects,' writes Basu. In Gandhi before India, Ramachandra Guha mentions Abdul Karim as one of the two key influential Indians in London at the time of Gandhi, the other one being Dadabhai Naoroji. As opposed to Naoroji, who moved to London in 1855 and let his interest in politics supersede his business, Karim was more 'discreet' in his influence. 'He taught the Queen Hindustani, with digressions into Indian religion. The Queen thought her teacher 'really exemplary and excellent'; under his direction, she had begun greeting Indian visitors in their own language,' writes Guha. Historian Lawrence James writes about Karim's influence in terms of the British empire's attitude towards Muslims in India in Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India: 'A Muslim, he may have prompted the Queen Empress's partisan remarks to Lord Elgin after Hindu-Muslim clashes in Bombay in 1894. 'Mahommedans should be protected, and their worship not disturbed,' she demanded, for, 'They are the real supporters of the British government'.'

In 1890, the Queen wrote to the Viceroy of India, Lord Lansdowne, and the Secretary of State of India, Lord Cross, to provide a grant of land for Karim in India, much to their chagrin. Writes AN Wilson in Victoria: A Life, 'Lord Lansdowne was uneasy about the request, since there was no precedent for such a grant being given to an Indian attendant. Land grants were normally only given in recognition of long military service.' The grant was subsequently given to Karim in the suburbs of Agra. He had also begun to feature in Court Circulars, which often labelled him 'the Queen's principal Indian secretary'. In 1893, Karim's wife and mother moved to England, and the family shifted to Frogmore Cottage, Windsor. Back home, his father, Waziruddin, was included in the list of 'New Year Honours' by the viceroy, and conferred the titled of Khan Bahadur.

Karim briefly came under suspicion for his friendship with Rafiuddin Ahmed of the Muslim League. 'The Household feared that the Queen was showing the Munshi her confidential papers from India and he was passing the information on to Rafiuddin. Everything that the Munshi did was now closely observed and Rafiuddin's movements monitored,' writes Basu. The issue subsided but the ill-will towards Karim remained. The Queen, however, was unshakeable in her resolve to give Karim 'what he deserved'.

In 1900, the Queen suffered a serious bout of illness, and passed away on January 22nd, 1901. 'Once the coffin was arranged, [her physician Sir James Reid] called in the family and members of the Household to see the Queen. The Munshi was summoned at the very end,' writes Basu. With the Queen's death, it was all over for Karim. The royal household was quick to get rid of all forms of correspondence between the Queen and Karim, including Karim's personal journals and accounts, as ordered by her successor Edward VII. He was unceremoniously sacked and deported. At his grave in Agra, Saxena reiterates the story with an addition: "He came back a pauper. He didn't have much before he died." His house, Karim Lodge, no longer exists. He died in 1909 with no children but his wife and nephew Abdul Rashid by his side.

The first comprehensive study of Karim's life was published by Basu. In 2001, she was at Osborne House when she saw a portrait of a 'handsome young man in a reflective mood, holding a book in his hand', painted by Austrian artist Rudolph Swoboda. 'He looked more like a nawab than a servant. The artist seemed to have captured the Queen's romantic vision of the subject,' writes Basu in Victoria & Abdul. With no personal records, Basu's journey was long and arduous. "The whole journey took me four years. Since the letter[s] had been destroyed, I had to piece together the story from different sources," she says, "I used Queen Victoria's Journals and her Hindustani Journals. I used the private papers of her Household. I went to Scotland to meet the family of her personal physician and used his diaries. I referred to the letters of the Viceroys and the secretary of state for India, and newspaper sources of the day."

Shuttling between Agra—where the Regional Archives possessed a handful of documents related to Karim's property, taxes and expenditure—and Windsor, she recreated, for the first time, the larger-than-life journey of 'Queen Victoria's ustad'. The release of the book also brought out the descendants of Karim— the daughter of Abdul Rashid, Begum Qamar Jehan, reached out to Basu—and also, for the first time, Karim's only existing personal journal. "Finding these was like finding gold dust. No one had seen them for over a hundred years. The journal is in his own voice, which is so important. It gave me an insight into his early life and his impressions of England. There were many details there that were very interesting and helped me complete the picture," says the author whose book gave birth to Frears' film.

Even as the mainstream media, Indian as well as Western, takes up the story, Saxena says that in Agra, it didn't quite catch the fancy of the people when he had written about Karim a decade or so ago. "I was the first one to write extensively on Karim and the derelict condition of his grave. My story was met with a lot of criticism from the Christian and Anglo-Indian community," he says. Basu, though, claims no such response after her book came out. "I knew people would be intrigued by the story. The book got excellent reviews," she says.

In Agra, the Regional Archives is the only remnant of Karim's legacy. Keen to gain access, I place a phone call to Ramesh Chandra, the Regional Archives Officer. "Abdul Karim? Of course, you are free to come here," he says, "I must tell you, though, there isn't much." On the day of our visit, Chandra sits at his desk with a total of five files, comprising stacks of yellowed pages acquired from government offices. There are maps, land documents and expense reports, among others. Some of the papers crumble with a mere touch. "Once, madam [Basu] had come to research for her book. Then Abdul Karim's relative also came," he tells me. Suddenly, his eyes light up. "There is a relevant document here which lists the attendants of the Darbar. Karim's father's name is here. That is very important," he says, sifting through the files hastily. After 45 minutes, he gives up. "It is somewhere here. The material on Karim is so little, it's impossible to lose." The scene serves a reminder of Karim's own curtain call in the annals of history. Behind his gravestone is an apt inscription in Urdu reflective of his state: One day everybody has to enjoy the sweetness of death.