Can the Saint Save Them?

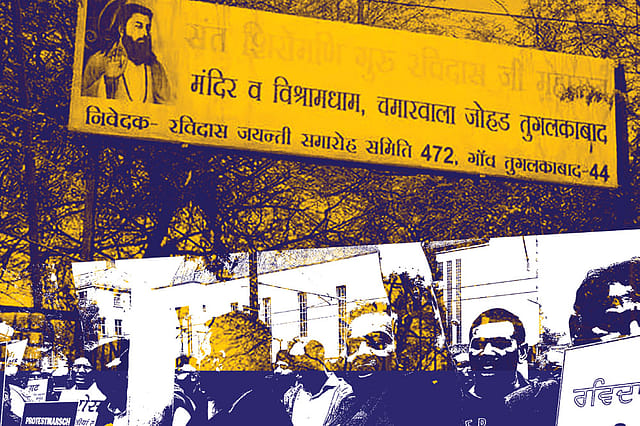

THE GATES LEADING to the complex where the Ravidas Temple stood, in a green belt of south Delhi's Tughlakabad area, are shut. A policeman, standing outside amidst the yellow barricades, says there's nothing inside. Security has been tightened after protests. On August 21st, as television channels tracked every moment leading to the Central Bureau of Investigation arresting former Union Minister P Chidambaram in the INX Media case, thousands of protesters marched across the city—from Ramlila Maidan to Tughlakabad—a week after the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) demolished the temple, dedicated to the Dalit spiritual leader and social reformer. Carrying blue flags, blue cloth tied on their heads, anger in their eyes and holding posters with images of their gods—Ravidas and BR Ambedkar—Dalits clashed with the police when they were stopped from visiting the demolition site.

Legend goes that Ravidas, a 14th century Bhakti saint born into a family working with dead animals' skin to make leather products, had miffed Brahmins of Kashi due to his rise as a towering spiritual guru, with even kings and queens seeking his blessings. Brahmins approached the king to complain against the Dalit guru. The king ordered a shaastraarth, a religious and philosophical debate, between a team of Brahmins and Ravidas, whose spiritual words drew praise. While Brahmins set out a host of rituals, Ravidas spoke of spirituality and purity of mind, says Dalit ideologue Chandra Bhan Prasad. He emerged victorious. The king then took him on his royal chariot for a round of the city, where at that time Dalits, then known as Untouchables, were even barred from taking a dip in the Ganga. "This episode was seen as the first Dalit victory in known history and it left a deep imprint on the mind of the community.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

In the Dalit psyche, the demolition of the temple is seen as revenge by the losers: the upper castes," says Prasad. He recalls that as a student, growing up in Azamgarh, just around 80 km north of Varanasi, he would see Dalits often declaring their caste as Ravidassi. A leading figure of the Bhakti movement, a theistic trend, Ravidas, was a revered figure in Dalit homes, stretching from Uttar Pradesh to Punjab and even large parts of central India.

The DDA had demolished the temple following Supreme Court observations on August 9th that a 'serious breach' had been committed by Guru Ravidas Jayanti Samaroh Samiti by not vacating the forest area as the court had earlier ordered. Undeterred by the protests, the apex court bench maintained that it was not concerned with political considerations and its orders cannot be given a political colour. But, like any emotive issue related to faith, outside the realm of the judiciary the demolition took an aggressive political turn. What lay razed to the ground amidst the trees behind the high walls of the complex in the national capital denuded a labyrinth of subliminal caste strife, undying faith and politics of identity. The opposition, reeling under its electoral losses, saw in the demolition an opportunity of forging a strategy to turn the tables on the Bharatiya Janata Party, which has projected itself as the deliverer for the underprivileged like Dalits, appropriating their icons and heroes. Ravidas was revered even beyond the Hindu pantheon. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a Member of Parliament from Varanasi, has also not missed the chance of invoking him. In February this year, ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, in Varanasi's Seergowardhanpur, Modi, while laying the foundation stone of Guru Ravidas Birth Place Development Project, pointed out the saint wanted a society free from caste or class discrimination, adding that his Government was committed to realising that goal. A year earlier, Modi had tweeted: 'I bow to Guru Ravidas Ji on the special occasion of Guru Ravidas Jayanti. His pure thoughts & ideals have a profound impact on society.'

The demolition of the Tughlakabad Ravidas temple, in a 'green zone', sparked off a Dalit protest in a polity that is yet to rise above caste lines over six centuries after the death of the reformer saint. The opposition stood with the protesters, who chanted "Mandir vahin banayenge" (We will build the temple there only), appropriating the Ram Janmmabhoomi movement's slogan in Ayodhya. Even the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which goes by Marx's dictum that religion is 'the opiate of the masses', has sought reconstruction of the temple and samadhis of four priests there. In a letter to Union Urban Development Minister Hardeep Puri, CPM Politburo member Brinda Karat accused the DDA, under his ministry, of riding roughshod over the 'legitimate' grievances of the petitioners and sought redress by asking for a review petition before the Supreme Court. Comparing the Government's approach on the Ram Mandir with the Ravidas Temple, she blamed it of having double standards. 'On the one hand, the Government is in court in defence of the 'faith of people' on the demand to build a temple in Ayodhya on the exact spot where the Babri Masjid stood. On the other hand, a spot which has been for decades a pilgrimage centre for the devotees of Guru Ravidas and on which a small temple structure was erected in the decade of the fifties, has been demolished by the same government.' She pointed out that the temple had been operational since well before Independence and devotees had been coming there especially for a pond where they believe Ravidas had visited. The structure demolished on August 10th was built in the 1950s to replace a makeshift structure there.

The Congress wasted no time in accusing the BJP-led Government of hurting the sentiment of Dalits, with its leaders demanding the temple be rebuilt. Soon after the protests led by Chandrashekhar Azad's Bhim Army, Congress General Secretary Priyanka Gandhi Vadra tweeted: 'BJP Government first messes with the Ravidas temple site, a symbol of the cultural heritage of crores of Dalits. And when they raise their voices against this, BJP resorts to lathi charge, orders use of tear gas against them and also gets them arrested,' adding, 'This insult to the voice of Dalits cannot be tolerated. This is an emotional matter and their voice should be respected.'

Describing it as a 'matter of faith' for millions, Delhi Chief Minister and Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) leader Arvind Kejriwal offered to swap 100 acres of forest for the plot where the Ravidas Temple stood. He said the solution lay with the Centre and claimed around 120-150 million people wanted four-five acres allocated for the temple. The Delhi Assembly has passed a resolution urging the Centre to allot land through an ordinance for a 'magnificent' Ravidas temple.

Political scientist Badri Narayan acknowledges that the issue has tremendous potential for politics as Ravidas is a symbol of equality and—like Kabir, his older contemporary, and Ambedkar—is an identity marker. According to Satish Kumar Rai of the Rajiv Gandhi Study Circle, while a "smaller identity should not dominate a bigger one", it is the responsibility of all political parties to create a healthy public opinion, abjuring fanaticism. The demolition of the Ravidas Temple, he says, has hurt the sentiment of a group and a way out should have been explored.

In Punjab, where Ravidas, whose hymns are included in the Sikh scriptures, has a large following, Chief Minister Amarinder Singh has said he will lead a delegation of the community members to meet Modi, seeking his intervention. The issue has reverberated in the state, which has the highest share of Dalits in the country, at 32 per cent. Fearing a backlash, the BJP's ally in the state, Shiromani Akali Dal, has also demanded the Tughlakabad temple be rebuilt. SAD President Sukhbir Singh Badal, after meeting Home Minister Amit Shah, tweeted: 'We pointed out that the land for the temple had been given to the Ravidas community by Lodhi dynasty in 15th century so it should be rebuilt at the same site.'

The opposition, sensing in the Dalit anger scope for regaining the faith of Hindus—even if just a section, is challenging the Modi Government's outreach across castes. The BJP, which claims to be to the natural claimant of the Hindu ethos, has astutely strung together a new caste combination, establishing affiliations beyond its traditional base of Brahmins, Thakurs and Baniyas. Even as it worked with castes, the party cut across them, capturing votes even among underprivileged communities. The BJP's electoral success lies in its ability to intertwine religion and caste. In the demolition of the Ravidas Temple, the party's rivals see an occasion to capitalise on a 'matter of faith' to halt that success. For the BJP, mentored by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the tryst with Hindutva politics began during the Ayodhya movement in the 1980s. It, however, could not tap the caste arithmetic, till the rise of Modi.

After a resounding victory in Lok Sabha elections this year, Modi, in sync with the party's ideological agenda, resolutely went ahead with keeping the BJP's long-pending promise to bury Article 370, which gave special status to Jammu and Kashmir, an issue which has resonated from the north to the south. The decisive move, amplifying Modi's popularity in the BJP's core constituency, created further unease in the opposition. Some Congress senior leaders like Jyotiraditya Scindia, Janardan Dwivedi and Deepender Hooda defied the party line and backed the Government's sudden move, a Hindutva plank infused with nationalism. Scindia tweeted supporting the separation of Jammu and Kashmir from Ladakh and the former's 'integration' into the Union of India. Adding that it would have been better if the constitutional process was followed, he said it was nevertheless in the country's interest. Dwivedi said his mentor Ram Manohar Lohia was opposed to Article 370 and a ''mistake of history [had] been corrected". Hooda described it as in the interest of national integrity and the state. The Congress' chief whip in the Rajya Sabha, Bhubaneshwar Kalita, when asked to issue a whip to members to vote against the Kashmir Bills, quit the party and joined the BJP.

Either out of conviction or because of diffidence about toeing a line that could further alienate Hindu voters, the Congress is faced with ideological questions from within. While political pundits concede that secularism never won elections—not even in the time of Jawaharlal Nehru—they do not deny that the BJP cannot be challenged on its own turf. Former Congress President Rahul Gandhi had last year visited temples, asserting his Hindu identity, seen as an attempt to alter the party's secular template to reach out to Hindus. However, at the August 9th meeting when the party was to choose a new president, Gandhi, without naming any leader, is understood to have explicitly conveyed that the Congress should refrain from emulating the BJP's Hindutva line. A disillusioned Congress leader, who did not want to be named, says while the BJP has clearly outlined what it stands for, there is ambiguity on the Congress' position. While some of its leaders are increasingly apprehensive of continuing with a secular approach, particularly on matters of nationalism, a large section in the party is opposed to soft Hindutva and wants the party to carve out an identity for itself without diluting its core values.

WEST BENGAL CHIEF Minister and Trinamool Congress chief Mamata Banerjee, under attack from the BJP for Muslim appeasement, has said more Durga Pujas were being held in the state under her government than under the previous Left regime. While Banerjee has made it a point to display her secular credentials, she has also declared herself to be a Hindu who knows more about her scriptures than those who question her faith. Recently, calling herself a devotee of Jagannath, she announced a temple dedicated to the deity at Digha in East Midnapore district to turn the sea resort into a religious tourism hub.

For the opposition parties, the futility of adopting the Hindutva matrix stems not just from the BJP being its primary beneficiary, but also from the fact that it would be myopic to base their strategies on the assumption that Modi's popularity emanates from ideology alone. He has flaunted a developmental vision—not just an ideological one—that pledges to change the lives of the poor. After LPG cylinders to women below the poverty line, he is now promising piped water. The next electoral test for him and the opposition is in Maharashtra, Haryana and Jharkhand. While the BJP plans a month-long campaign on Jammu and Kashmir, reinforcing nationalism, it may be time for the opposition to go back to the drawing board.