When Edwina Missed India and Nehru

THE MOUNTBATTENS arrived at Northolt to be met by Patricia, Prince Philip, Clement Attlee and the Indian High Commissioner, Krishna Menon. Edwina, still emotional after her parting, made a short speech about what India meant to her. Her younger daughter remembered how: ‘she began to falter, and she had difficulty in getting the words out, ‘. . . every . . . possible . . . feeling.’ She stopped, blinked, then licked her lower lip until for a horrifying moment I thought she might break down. Then, as she turned to my father for support, he gave her a warm, confident smile and she regained her composure and found the strength to continue.’

For Edwina, life in drab post-war London after the vibrancy and energy of India seemed trivial and low-key. She fell into a deep depression, exacerbated by exhaustion and the loss of her beloved Sealyham terrier, Mizzen, who had had to be put down en route to Malta.

After the splendours of Government House, 16 Chester Street seemed claustrophobic. Only Broadlands provided the peace she now needed. She missed the pace of life, the status, the sense of purpose she had enjoyed in India, and tried to replicate it. ‘I have resorted to very hard work as a possible solution to the present situation,’ she told Nehru at the beginning of July, ‘it has helped although it is really only a drug.’ ‘Feeling quite awful,’ she confided to her diary the following month, ‘general exhaustion and depression, I think.’ ‘Life is lonely and empty and unreal,’ she confessed to him. Above all, she missed India and Nehru.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

She would write to Nehru each day, following Dickie’s habit for confidential correspondence of enclosing her letter in a second envelope. At first this was marked ‘Prime Minister’ and later ‘For Himself ’, numbering each letter so each could be accounted for. Nehru, in turn, would write using the diplomatic bag c/o the High Commission. Whereas Dickie’s letters had been prosaic, Nehru’s were like poetry, indeed often quoting poetry—either his own or Yeats, Swinburne, Auden, Joyce and Blake. When no letter was received, like a lovesick teenager, she would call India with the help of half a dozen operators.

People did what they could to cheer her up. Malcolm Sargent took her to see Laurence Olivier in Hamlet. In August, the whole family went to Classiebawn for five days, staying in the local inn, whilst they brought the house back to life. The fresh air and peacefulness helped restore her good spirits. ‘Scrambled over the rocks and dabbled in the pools,’ she wrote to Nehru, energised. ‘Back by the beach of white sand . . . brilliant sun and sapphire and multi-emerald coloured seas and countryside with its white-washed thatched cottages . . . we shrimped off the rocks and sat about in shorts sunbathing.’

In September the Mountbattens, with Pamela, stayed with Henri and Yola Letellier in the South of France, where Dickie practiced his water-skiing and they saw the Duke of Windsor. But Edwina remained dissatisfied. ‘I somehow seem to have grown out of all this, the people, the life, even the scenery,’ she wrote to Nehru.

For Dickie it was different. Though he had been offered various jobs, including Governor of Malta, Governor General of Canada, and Ambassador to Moscow and Washington, he just wanted to resume his naval career. He had put together an eight-page document headed ‘My Next Appointment’, which laid out all the possibilities and he discussed this endlessly with Peter Murphy and Charles Lambe. His two main options were to go to Bermuda as C-in-C West Indies, generally regarded as a pre-retirement job; or to return to Malta, which might prove politically difficult, given the problems in Palestine, and embarrassing as he would be subordinate to the Commander-in-Chief.

Whilst Mountbatten had received praise for the transfer of power, it had been at a price. Dickie recollected how, shortly after their return, Churchill came up to him at a Buckingham Palace reception —“What you did in India, it’s as though you struck me across the face with a riding whip” and he turned his back on me and he didn’t speak to me for several years.” Mountbatten, however, continued to take an interest in the subcontinent, especially as many issues from his time played out after his return.

On 11 September, Jinnah died of cancer, weighing only 35 kilos. The ambulance taking him to hospital broke down and for an hour he lay dying, parked on the roadside. Mountbatten later reflected that if he had known the seriousness of his illness, he might have delayed independence, and there may have been no partition.

In October, Nehru came to Britain for discussions on the Commonwealth, before going on to the United Nations in New York. Dickie tactfully left the reunited lovers alone for a midnight rendezvous en route from the airport. ‘Too lovely,’ Edwina noted in her diary. Whilst Dickie initially stayed in London, the two spent several days at Broadlands, where Nehru entertained Patricia’s sons by ‘getting down on all fours in the drawing room and making lion faces at Norton and his new brother, Michael John, who roared back in absolute delight.’

For the next week they were inseparable. They visited Jacob Epstein’s studio, Edwina joined Nehru on the platform at a meeting at Kingsway Hall, they saw Euripides’ Medea, jointly attended the Lord Mayor’s banquet, a reception at the King’s Hall and a dinner for Dominion Premiers at Buckingham Palace, and were photographed at a Greek restaurant in Soho after the press were tipped off by Krishna Menon.

AT THE END OF October, the Mountbattens returned to Malta, Nehru seeing them off from Northolt and Edwina in dark glasses to hide her tears. Dickie, who had been appointed as Commander of the First Cruiser Squadron, now reported to Manley Power, who insisted on continuing to call him ‘sir’. It must have been a huge adjustment, from having ruled a subcontinent to an island just over 300 square kilometres; from having given orders to now being a subordinate. Power, initially wary, grew to respect his new colleague: ‘We saw eye to eye on most important matters. I found him an endless source of entertainment with his peacock Mountebankery which kept popping up at unexpected moments in sharp contrast to his normal sane and statesmanlike person . . . By the end of my time with Mountbatten I had reached the conclusion that, in spite of several failings, he was a great man and a statesman. He was dynamic, easy to deal with and always open to argument, with a tremendous gift of charm and inspired leadership.’

Their old house, Casa Medina, had survived the war, but was now converted into flats, so they first stayed at the newly opened Phoenicia Hotel before moving, shortly after Christmas, across the road from the Case Medina to the Villa Guardamangia. Royal Marine Ron Perks was assigned as Mountbatten’s driver and lived at the Villa Guardamangia whilst it was being decorated.

Perks would often drive Mountbatten to his scuba diving or to polo practice, ‘where he spent hours practising on a stationary horse in an enclosed area with the ball ricocheting round. You could be very relaxed with him. He never stood on ceremony.’ He recollected how once driving through a 40-mph area, Mountbatten, who loved to drive fast, told him to ‘Step on it’: ‘I explained about the speed restrictions and he insisted we swop places which we did. A few minutes later the military police, who we called Snow Drops on account of their white helmets, stopped us. After saluting me in the back they proceeded to give the driver a bollocking until they realised who he was. We then swopped places again and I drove to our function.’

Whilst Dickie quickly threw himself into his new responsibilities, Edwina felt trapped. ‘One feels one’s brain and even one’s energy shrinking to fit the tiny island,’ she told Nehru. She continued to work for St John Ambulance and Save the Children, and Pamela became a case worker for the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen Families Association. Eventually she settled into a routine. ‘You will be pleased to hear that Edwina has been quite relaxed & very sweet & we never have a cross word — more like 1928 than 1948,’ Dickie wrote to his mother. ‘Still I think it a very good thing that we should have good long periods apart for we have been on top of one another for too long’.

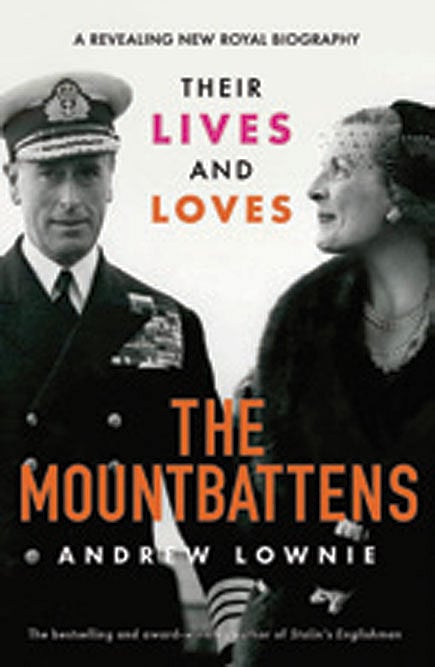

(This is an edited excerpt from The Mountbattens: Their Lives & Loves by Andrew Lownie | HarperCollins | 490 pages | Rs 699)