The Problem with the Illiberal Label

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 15TH, came and passed rather uneventfully, much like any other day of the week. If one takes a random sample of people and asks them the significance of September 15th, chances are that no one would know that it is the UN-designated "International Day of Democracy", meant to celebrate and uphold the principles of democracy.

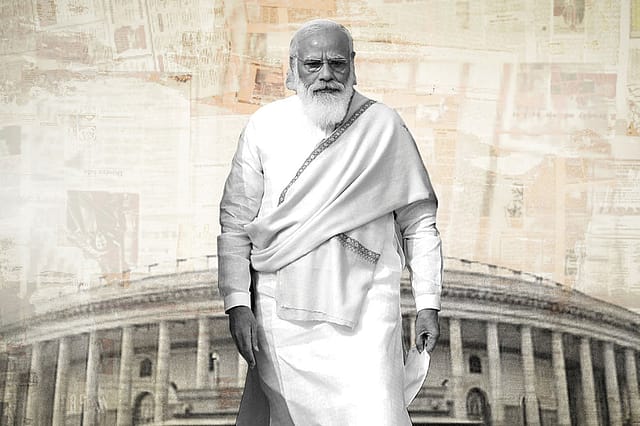

On that day, in India, there were a handful of surly op-eds, editorials and some tweets about the country being less than a democracy. One assumed there would be a lot of noise that day but there was, instead, a strange silence. There is now a long list of expressions that describe India's "downgraded" status: "partly free democracy," "electoral autocracy," and more. Every year, since Narendra Modi became prime minister, reports released by Western thinktanks routinely chip away a notch or two from India's status as democracy to the point that one would imagine that there's no freedom left for people who live there.

Part of this is noise dictated by the conjuncture. Between early January, when Joe Biden assumed the presidency of the US and late July, when his Secretary of State Antony Blinken made his maiden visit to India, the pitch against India being no longer a proper democracy rose to a crescendo. Near-total absence of human rights, a tamed judiciary, an overbearing executive and, of course, Muslims being rendered second-class citizens were routine allegations and were made almost on a daily basis. Then, all of this died down suddenly.

The din had much to do with expectations from the Biden administration giving India a tongue lashing, if not more. Some even imagined substantial punishment. But when Blinken came and went without administering any 'punishment', the hopes of scores of intellectuals, activists and, more alarmingly, some Indian politicians were dashed. India continues to be considered and accepted as a proper member of the society of democracies.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

In reality, India remains a democracy and has been so except for a brief period when elections were suspended and fundamental rights curbed across the land. But that has not deterred thinktanks and their India-based 'experts' from inserting multiple qualifications in calling India a democracy. In various reports, such as the ones issued by Freedom House, V-Dem Institute and others, India has lost out not so much on the democracy bit, but on its alleged lack of civil liberties. In the Freedom House report for 2021, issued in March this year, India was classed as a "partly free" country, mainly on account of its poor civil liberties record.

The issues that have led to this problem in no way impinge on the functioning of democracy. For example, the abrogation of Article 370, the passing of the Citizenship Amendment Act and the Supreme Court ruling in favour of the Government are some of the issues behind these downgrades. The Government and informed citizens, in general, consider these issues to be the business of India and no one else. Much of this is, of course, political: Virtually all the 'experts'—on whose testimony India's rankings are decided—loathe the Government, but are powerless to do anything about it. That right remains firmly in the hands of citizens. There is, however, a substantive issue as well. One can ask whether India is indeed a diminished democracy to the point that it does not merit that designation.

The answer is complicated and is best found by comparing India with its twin, birthed in 1947, Pakistan. The story of Pakistan's democratic breakdown is complex, but two elements are salient in its political descent. One: the dominance of a single province—Punjab—in virtually all aspects of its national life. Two: the dominance of its army—an unelected institution—over elected organs of the country. The "why" of these developments need not detain us, but the result is obvious: a singular concentration of power in very few hands by unelected means that has persisted since 1958.

In India, the story is the polar reverse: there is no one province that can dominate others. To be sure, Uttar Pradesh has the highest number of seats in Lok Sabha but if one were to consider this as some sort of domination, all one would get is faint amusement. The armed forces, unlike their Pakistani counterparts, are exemplary citizens who know, and heed, what is expected of them.

India's troubles—ones that are being used to beat down its democratic record—stem from a different source: the widespread internal turmoil that has necessitated the use of armed force to quell secession and separatism. This is a general problem that has persisted since some years after India's Independence. In some cases—the erstwhile province of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) and Nagaland are examples—extremely harsh measures have been used over time by all governments. The first application of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act was in Nagaland, when it was part of Assam, in 1958. This was done when Jawaharlal Nehru was the prime minister. It continued till the tenure of Narendra Modi. J&K presents a similar picture but one that emerged a bit later. There were other cases where 'democracy was suspended', such as Punjab during the phase of terrorism in the 1980s, when it remained under presidential control.

India's problem, if it can be expressed in stark terms, is between territorial control and uniform democracy at all times. The two have been mutually exclusive, in secessionist provinces. Anyone who has studied separatism in India's disturbed provinces knows that having only one of the two features at a time is a bad idea. But it is also true that no country—democracy or non-democracy—will let go of its territory willingly, least of all, for the sake of democracy. India has tried a mix of different options at different times in these difficult provinces. Even in J&K, duly elected governments have functioned when terrorism raged there. These are, however, not permanent problems. In Punjab, once terrorism was finished, all normal political processes resumed fairly quickly. Something of that kind is at work in Nagaland as well. That will happen in J&K, in due course, as well. In fact, the process of delimitation of constituencies and elections after that is already on.

Every prime minister who has dealt with J&K has tried in his or her own way to ensure its tighter integration with the rest of the country. Across political parties, the mischief done by Article 370 is well-known. But ending it required political authority—on the basis of a legislative majority empowering the executive—that remained illusory for the last three decades. During this period, the intellectual climate in India turned sharply against the idea of integrating J&K into India as a normal state. Intellectuals and activists built careers in making the case for separatism or, even worse, some kind of a "sharing arrangement" with Pakistan. Nagaland was similarly held as a "blot" on India's record. Should it surprise anyone, then, that these intellectuals seek to exact their revenge by describing India as something less than a democracy? It is a price that India can live with. Labels don't matter; what matters is that the people of India have a full say in electing those who govern them. That right remains intact and unalloyed.