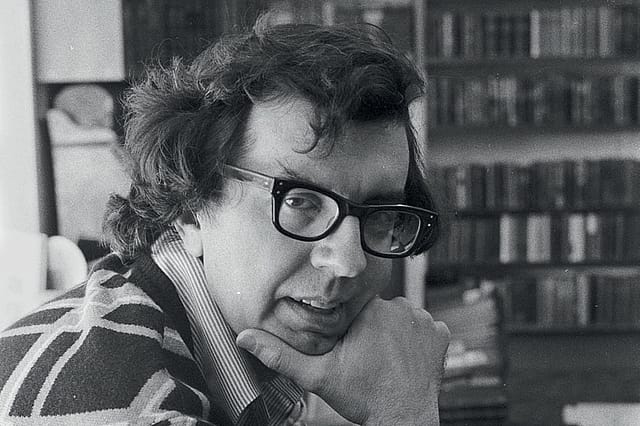

Larry McMurtry (1936-2021): Book Rancher

THE AMERICAN WRITER Larry McMurtry, who died recently at the age of 84, was both a critical darling and a bestselling author. His works were often turned into films and TV shows featuring some of the biggest stars and directors of the day, from Paul Newman in Hud (based on his first novel Horseman, Pass By) to the Sidney Lumet-directed Lovin' Molly (based on his second novel Leaving Cheyenne). Many of these films bagged Oscars. And McMurtry would himself win an Oscar (along with his co-writer Diana Ossana) for adapting the screenplay of Brokeback Mountain.

McMurtry's primary interest was Texas, the place where he was born and spent the majority of his life. And he explored the myths and legacies of the American West again and again, novel after novel. At one point, he would even be seen sporting a t-shirt with the tagline 'minor regional novelist', a label once slapped upon by a critic.

McMurtry's best-known work remains Lonesome Dove, an epic novel centred around two ageing Texas Rangers. The historian Douglas Brinkley once wrote in the New York Times, 'Some claim the three essential books in Texas history are the Bible, the Warren Commission report and Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove.' It was a novel that sought to demythologise the Western. But its success—winning a Pulitzer Prize, having a multiple Emmy-winning TV miniseries starring Tommy Lee Jones and Robert Duvall based on it, and the several many books and more TV miniseries in this franchise—meant that it ironically became the very thing that it sought to break free from. 'I thought I had written about a harsh time and some pretty harsh people,' he would later write in the preface to a 2000 reprint of the novel, 'but, to the public at large, I had produced something nearer to an idealization; instead of a poor man's "Inferno," filled with violence, faithlessness and betrayal, I had actually delivered a kind of Gone With the Wind of the West…'

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

McMurtry was raised on a ranch in Texas. It was a book-free environment, he would describe in his memoir. And books would probably not have played such a central role in his life, had not a cousin, on his way to World War II, left behind a box filled with adventure novels, which the young McMurtry devoured. Apart from his writing career, that included over 30 novels, essay collections, memoirs and works of history, and over 30 screenplays, McMurtry also taught for a few years. But the successful adaptations of his books into movies meant he did not have to rely on academia for support. Instead, he channelled his passion for collecting rare books into a secondary career. In the late 1980s, he bought a string of abandoned buildings and, stocking them with his personal collection and other books he would continue to buy, he opened several antiquarian bookstores. He would wind these down in 2012, holding a huge auction of over 3 lakh items. "One store is manageable for my heirs. Four stores would be a burden," he was reported as saying then.

McMurtry also led a somewhat unconventional life. He moved in with Ossana after he suffered a heart attack in 1991. The stroke is believed to have led to deep emotional and psychological trauma, and Ossana helped him through this period, helping him resume writing, and editing and rearranging his work. This developed into a full-fledged collaboration and the two began co-writing their work. Ossana famously introduced Annie Proulx's short story Brokeback Mountain to McMurtry, and the two of them, having sought Proulx's permission, wrote the screenplay and pushed for the development of the film.

While Ossana and McMurtry denied having a romantic relationship, there remained a third figure in the family. After McMurtry's friend Ken Kesey, the author of One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest, died, he married Kesey's widow Norma Faye. With little fuss, the newlyweds moved into Ossana's house.

A few years after his stroke, when McMurtry was recovering and had begun to open bookstores in his hometown Archer, he described to the New York Times how, despite a different career path, he continued to feel a deep bond with the ancestors of his land. 'The tradition I was born into was essentially nomadic, a herdsmen tradition… The bookshops are a form of ranching; instead of herding cattle, I herd books. Writing is a form of herding, too,' he said.