These Walls Have Years

She listens to the walls of her beloved ancestral haveli and tries to figure out what it is about the house that really kept her family together.

They say that the walls of a house can speak, that they have a voice—if you only listen. I've come here every summer, ever since I can remember, to meet my grandparents. We live in one of those havelis in Old Delhi that stand out because everything seems to change around them, while they remain the same imposing structures. They are a dime a dozen in the area. But it never struck me until recently that my family's haveli might be more than that. Even as I write, it takes me a moment to see beyond the yellowed walls, the creaky doors and the Samsung fridge in the corner of our open chowk.

I'm moved to write about it not because I remember vividly every happy summer I spent in it, not even out of the nostalgia that comes with knowing that it will be reduced to a pile of sand and rubble in the next few months. I write this because this haveli has a story worth sharing: built in 1938 by Shri Phoolchand Jain who initially lived in Chandni Chowk, this haveli—aptly named Milap Bhavan—was the first sign of life in the locality that is known today as Malkaganj Chowk. Without the throngs of Delhi University students, the noise of street vendors and the eateries that it boasts of today, the area used to be one of uninhabited wilderness. At the time the haveli was built, my nani once told me, there was no water, electricity or any way of staying connected with the rest of the city. Phoolchand Jain, my great-grandfather, had a well dug for water with a pump in place, and hung lanterns in the house as well as in its surroundings areas. Most importantly, he had a post office constructed across the road that stands even today and is called the Jawahar Nagar Post Office. All this, to make a haveli a home. As the fifth generation of the Jain family to have lived here, I know that our home has since seen happiness and health, and its share of hard times as well.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

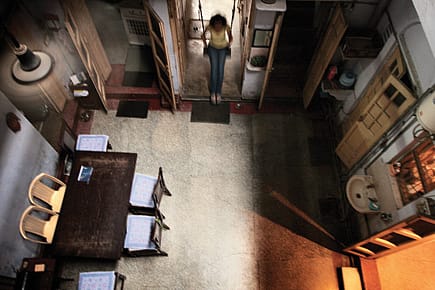

As I enter my house through the pauli or doorway, I reach the central part of the house, an open chowk. Standing in the centre and looking straight up, the blue sky has never seemed so close. With a small rasoi and what Amitav Ghosh calls a goozle-connah or washroom to the left, the chowk understates its most important feature—the taikhana or the dungeon. Usually the setting of horror films or a place for the dark experiments of madmen, our taikhana has a different story that dates back to 1942—the time it was constructed, well after the haveli was built. Because of the threat of spontaneous gunfire in the turbulence of pre-Independence, Phoolchand Jain—himself a stalwart of the Delhi branch of the Indian National Congress—had the taikhana built for the protection of his wife, Chameli Devi Jain, and their four children. Having been jailed six times during British Rule because of his politics, he foresaw the need for a safety zone within the house for his family and himself. It has a winding stairwell leading to a dark and damp space that used to have beds and was stocked with provisions. It would have been the perfect hideout. I've always known it as storage space for cardboard boxes, metal bins of rice, old toys and (dare I say) fat mice, so I never could tell why we even needed one. Then again, there was so much that I didn't know of my own house. No ordinary structure this, Milap Bhavan has always stayed true to its name, keeping a family together.

Another fascinating aspect of the house is the multitude of nooks and crannies that are a well-kept secret of the house, known only to its residents. Hidden in places no prying eyes would think of looking, these are typical of most havelis and known only to their residents. Hinting at their existence, however, are the less hidden cubby holes or aalas that are visible nooks carved into the wall. They take the shape of the flame of a candle but with a flat base—a relic of the past, reminiscent of the time when the women of the house lit diyas every day at dusk. The aalas now hold figurines, keys and bric-a-brac. Houses won't have them anymore because their function is so outdated—a realisation that made my mother misty eyed just last week. Funny, for she still has her family and will probably hold on to her childhood things that are in the house. But the destruction of the spaces in the wall for diyas is her greatest pain. I can't think of the last time she gave them any thought.

It really makes me wonder how much attachment I can have to each prosy brick that makes up this house. I always thought it was about the memories and the people, but it is just as much, if not more, about the physicality of life as well. I have been lucky; I've lived in this haveli and called it home. My children will probably not have that. Even that is a real loss that conjuncts with the eventual destruction of that first prosy brick. Today, the walls of Milap Bhavan have yellowed, and it has changed with time—what with the need for better plumbing, repairs and more power outlets for coolers, a computer and air conditioning—but even underneath the invasion of technology, Milap Bhavan keeps its secrets and its antiquities. But when my haveli is demolished, I know they will be lost.

And as the walls go down, so will their voice.