Mr Creepy Crawly

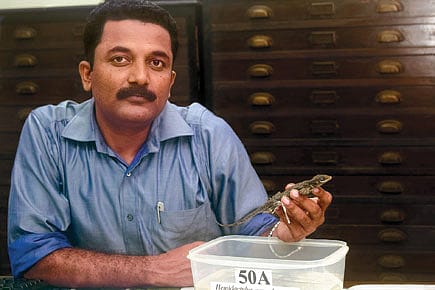

Herpetologist Varad Giri is a pretty rare creature: a researcher who can't have enough of the creepy crawlies

I am a herpetologist—a researcher and discoverer who devotes himself to the study of reptiles and amphibians. I'm a staffer at the Bombay Natural History Society in Mumbai and I often find people overcome by the 'ooh factor' when I tell them about my work. I get a lot of, 'Oh, it must be risky to research wildlife, deep in the jungle.' Adjectives like brave and glamorous are, I think, used a bit too often for my comfort.

I don't quite see it that way, though. To me, my work is my passion and I enjoy doing it more than anything else. And really, I don't quite get this idea of a 'dangerous jungle'. Aren't our roads dangerous as well? For me, the jungle is the most interesting place. I feel really invigorated when I discover something new. If you get afraid, how can you do any work or discover anything? As far as my 'bravery' goes, I take care to watch my step and give the animals their space, and they do not go out of their way to harm me as a result. In fact, in the jungle my biggest grouses are leeches, mites and ticks. One cannot say as much of the city. One might just get run over by a speeding car.

When I'm not in the jungle, I can be found at my desk at the BNHS office at Kala Ghoda, writing reports, working on papers, cataloguing information or fact-checking, handling administrative matters, and curating the BNHS collection. Also, I am working with two NGOs to train people in remote areas to make their own observations and do their documentation themselves.

I go exploring the Western Ghats' jungles for 10-12 days at a stretch. The Western Ghats are known as a bio-diversity hotspot. Many species of reptiles and amphibians here are unknown to science to this very day—it is so rich in wildlife and so little explored. I have obtained grants from various organisations to find and describe these species. Since 2003, even though I have managed to work through less than 10 per cent of my focus area, the northern parts of the Western Ghats, I have already come across two species of lizards and three amphibian species unknown to science.

2026 Forecast

09 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 53

What to read and watch this year

My latest discovery has been reported this year. In 2005, I was in the jungles of the Ghats searching caecilians, a family of legless amphibians resembling earthworms though they are a different species altogether. Caecilians are also slimy to the touch. They are amphibious and possess eyes and toothed jaws, beside having skeletons. Finding these involves turning over rocks, a little digging, sifting through piles of leaves—in other words, getting your hands quite dirty.

Actually, I had discovered one species of caecilian in the Ghats earlier and was out looking for more. I was with the Green Guards, a group of wildlife enthusiasts from Kolhapur whom I am friends with. This was the rainy season, and at one spot in the Ghats (I am not telling which one, for fear of sightseers), we saw almost 50 geckos out on the rocks in a fifty-metre area. Suddenly, one friend came up to me with a lizard in his palm and said, 'Hae kAhitari navIn vATtay.' The gecko was forty millimetres from head to tailbase and forty more up to the tip of the tail. There was a greenish-blue iridescent sheen to the gecko's body when you looked at it from an angle. No geckos have iridescent colours. This one did. A friend in the party persuaded me to research it.

As I later found out, with the help from my friend Aaron Bauer in the US and colleague Kshamata Gaikwad here, it was a species never described before. I think it comes out in the open only during the monsoon. It seems quite common in the Ghats.

Another link discovered in the biological chain. It's quite a big deal, really. Geckos may not be as charismatic as tigers, but they have their own importance in the scheme of things. This year, the discovery was ratified with our research paper getting published in the science journal, Zootaxa. The lizard was named Cnemaspis kolhapurensis, after the district in which the discovery site falls.

Discovery to ratification took me four years. I had to compare this species of lizard with every lizard species reported so far. Of course, my friend and lizard authority Bauer helped considerably. Plus, I just wanted to make sure I wasn't wrong. Because Indian herpetology is in a mess with many wrong identifications. And five years down the line, I didn't want to turn out wrong. Fortunately, this lizard was completely unique in appearance and colour. If it wasn't, we would have to take it to a DNA testing laboratory.

This was my fifth discovery. Since 2003, I have discovered two lizards and three caecilians, all in the northern parts of the Western Ghats. If there are reptiles and amphibians of so many varieties here, then the insects must be incredibly diverse, too. Perhaps, somebody should look into this. Insects are among the least studied species.

Now all my research since 2003 has cost less than Rs 15 lakh. Contrast this with the tiger project, which has a budget that runs into crores annually.

There are two kinds of animals: charismatic and non-charismatic. The tiger is a charismatic animal. So are snakes. Everyone wants to study such species. But if you're truly an animal lover, you should love an ant as much as a tiger. Logically speaking too, insects have to be studied because they are the base of the food chain.

In fact, I should think I'm a pretty rare species myself. There are not more than ten researchers in reptilian and amphibian studies in India today. Among them is my mentor, Ashok Captain, and S Biju, who helped bring attention to the Western Ghats a few years ago with his discoveries and writings. But most herpetologists are content to get degrees and just teach. As a result, there are few field researchers and as a result few mentors for the next generation of researchers. I was lucky, because I found mentors who recognised my passion. When I was in college at Dharwad, doing my PhD on silkworms, a friend convinced me to give it up in favour of wildlife research. That was Satyajit Mane, who is now in the Sales Tax department in Mumbai. He told me I should chase my passion. And he changed my life. Then there was Captain. So I do owe quite a lot to friends and mentors. Many people, far more brilliant than me, have never found a mentor and haven't been able to make it.

As a child, I didn't have any exceptional interest in reptiles and amphibians. I was the son of a purohit from Belgaum district, Karnataka, and no one in our village, Ankli, would have even known what research meant.

But as I grew up, I got curious about insects and I found myself in Kolhapur completing my MSc in entomology. No one at the university there was really into research. The library was the sole resource of knowledge. It was at this place that I got interested in birdwatching with a group of friends. I bought a camera and started taking pictures of birds. It's a tough thing to pull off. Being usually far off into the scenery, birds are hard to photograph.

As I didn't have an adequately powerful lens, I took to photographing reptiles instead, which are stationary and generally easier to shoot than birds. In other words, my lens was good enough to shoot them. That's really how I got close to reptile studies.

As I felt the need to catalogue my photographs and be absolutely thorough in my observation, I began to consult JC Daniel's book on snakes. He is associated with the Bombay Natural History Society which the book also mentioned. So I got this job, entirely by coincidence actually, on a visit to BNHS in 1999. I had come up to Mumbai to consult their library. That day they were holding open, walk-in interviews for researchers. A mentor told me to apply. I was promptly assigned their herpetology division. Ten years later, besides doing research, I handle their archive of reptile and amphibian specimens also.

There is a faint glimmer in our field these days. A few of the younger students are showing promise and, more importantly, the keenness to do research. I am confident that about ten of them will emerge full-fledged researchers across the country. Though at present, I have to admit, we are still searching for people to fill the two posts of researchers at our office.They have been vacant for a while now.

If I could do it, I would like to make the Western Ghats the subject of my life's work. There are so many more species left to find, especially those that are found nowhere else but in these jungles.

As told to Suhit Kelkar