As Amma Lay Dying

THE AIADMK HAD just come to power, four months ago. The jubilations were still on in the streets of Tamil Nadu. There was a pall of gloom that had settled in the corridors and halls of Arivalayam, the DMK headquarters. None of the members, not even Somu, the gardener, or Samuvel, the sweeper, in the precincts could believe that the party they had voted for did not come to power. They wondered how the lady at whose feet all those spineless men fell wherever they stood, even as she flew above their heads in a helicopter, was able to win the elections consecutively. It was rumoured that she drew her strategy to perfection, single-handedly without the help of the other leaders in the party. People flocked to see her like devotees rushing to see their deity in the temple. They trusted her as their redeemer and voted for her. They did not remember how corrupt her government was—that she was punished and jailed for corruption, though miraculously a judge later said she was not guilty. Could you believe such an incredible story? The gardener put his finger on his lips. The sweeper went back to sweep. Of course, who were we to judge?

Both Somu and Samuvel, however, were dumbstruck when the news came that Jayalalithaa was hospitalized and was in the ICU, possibly in a serious condition. How could that be?

The news took everyone by surprise. She had been seen hoisting the flag on 15 August. But the public rarely saw her regularly. That she was severely diabetic was in public knowledge for long, though she wanted none of it to spread. She probably had many more ailments that she wanted to be kept under wraps. But what would she have gained by such secrecy except harm to herself? The callousness with which she neglected her health, ignored the warning signals that her body gave, in spite of having a doctor, Dr Shivakumar, a close relative of Sasikala, at hand seemed unbelievable about a person who was super intelligent, who could devise master plans to defeat her political foes, however mighty they might be, and could come out triumphant. Reports suddenly started pouring of how she refused to take insulin injection even when the sugar level went as high as 500, and how she loved sweets and would not give them up at any cost.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

A spate of questions were raised. Why had Dr Shivakumar not been strict in instructing her that she was playing a dangerous game with her life? Why did Sasikala and the others indulge her when she demanded sweets like a child? Even the sight of a well-folded sweetened paan could trigger the taste buds and she would not stop eating a whole plate of it if kept before her.

If she was denied, she would be very upset and act demented, says Prabha, Shivakumar’s wife. Prabha claims to have been very close to her during the last couple of years—if so, why did she not use her good offices to impress upon her the health hazards of eating things that should have been considered poison? We were afraid, says Prabha. ‘Athai could get very angry, so we were careful not to annoy her.’ Why was Sasikala and company reluctant to get into her bad books, even when they knew that she should not be indulged in matters of food, when she was supposed to follow a strict diet? But the central question is, why did Jayalalithaa behave so foolishly when it came to her own health? It is indeed intriguing that a person who was well informed, and also one who relentlessly fought her way through in her personal as well as public life against great odds, was prone to dig her own grave by abusing her body.

It was an irony that she was considered a tough leader and a strong woman who could stand no nonsense. It was just a way to describe her exterior. Those close to her claim she was obstinate, arrogant and short-tempered. There was no line drawn when it came to intolerance to dissent even in matters of personal health. Those who were with her were her dependents, afraid to displease her, lest they be shown the door.

Alas, that was her Achilles heel. There were indications from childhood, from her schooldays. Chandini Bhulani, her former classmate, narrates an incident, which was then thought to be comical, a child’s prank. Jayalalithaa and Chandini competed with each other in consuming paan that they bought with their pocket money. Jayalalithaa ate so much that her tongue remained burnt for a few days. Her mood swings, reportedly ‘abnormal’ earlier, became worse after her mother’s death. The feeling of insecurity made her suspect the intentions of her relatives, advice given by Seeni Mama (Uncle Srinivasan) who had looked after her till she was ten in Bengaluru and loved her more than he loved his own daughter Anuradha. She resented criticism of any kind, given even in good faith, by a close friend or a relative. She cut herself away from her very close relatives, from blood brother to uncle and aunts, as well as close friends, who did not think twice before admonishing her if they differed from her. She was vulnerable.

Jayalalithaa distanced herself from everyone related by blood and friendship—so tough was her veneer that she did not respond to even deaths in the family, such as, when her aunt died and when Seeni Mama died. She seemed to have changed into a different person altogether.

Like her mentor MGR who was too vain to let the world know of his illnesses and was in constant denial, Jayalalithaa too was paranoid about visiting hospitals—mainly because the press would come to know about it. Dr Shivakumar says that she simply refused to go to the hospital when she was sick and needed a detailed check up. She demanded that specialists should visit her at her residence. ‘Expert medical examination or investigation could hardly be done at home.’ When she did have to go a few times, she would disguise herself and go to the hospital late in the night.

On the night she collapsed, on 22 September 2016, Dr Shivakumar says he had just come out from the operation theatre after attending to a surgery when he got a call from Amma that she had some breathlessness and low fever. He called the hospital to send a nebulizer to Poes Garden. Soon after, Shivakumar reached her residence. ‘Amma did not appear to be in serious discomfort’, but as she came out of the washroom, she fell down and passed out. He called for an ambulance immediately. It is not very clear what happened exactly. Shivakumar did not divulge much. The doctors at Apollo Hospital said she was unconscious when she was brought to the hospital at 11.30 p.m. But when she was carried into the ambulance from Poes Garden, Dr Shivakumar says that Jayalalithaa caught hold of his hand and did not let go of her grip. When her stretcher was taken in the lift, the driver who accompanied them says that she became conscious and asked where she was being taken.

THE HOSPITAL GAVE a press release: ‘The honourable Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu was admitted to Apollo Hospital Chennai with fever and dehydration. The honourable Madam is stable and under observation.’ As the news spread like wildfire, AIADMK functionaries and cadre started gathering around the hospital with anxiety. When the TV cameras panned you could see many women beating their chests and wailing ‘Amma, Amma!’ as if Jayalalithaa were already dead.

According to sources in the police department, between 500 and 1000 police personnel were deployed in and around Apollo Hospital at any given time. At least one additional commissioner of the city police, two joint commissioners were stationed around the clock. The tight security wasn’t just for the CM’s safety, but also to control the flow of information, it seemed. The chief minister was being treated on the second floor according to sources in the hospital. The entire second floor was cordoned off for her. No one had access to her except Sasikala and Dr Shivakumar. It looked as if Sasikala had taken charge of the security arrangements in the hospital. It was said that no cabinet minister or senior bureaucrat could go inside Jayalalithaa’s room. Every morning all the ministers in their crisp white veshtis made a solemn march to the hospital, hoping to see Amma, to just see how she was faring. But they could not cross the barrier in the person of Sasikala, who had, overnight, attained a status that was scary.

It was rumoured that the doctors had been asked by her to switch off their mobiles so that no news of Jayalalithaa’s health condition was leaked.

The VIPs that included Governor C. Vidyasagar Rao, Vice-President Venkaiah Naidu and Union ministers who came to pay a visit had to be content with just seeing Sasikala, and come out to say before the waiting journalists and TV cameras that Jayalalithaa’s condition was improving and they were happy about it.

There was an inexplicable silence that covered the premises like an ominous shroud. Nobody could say for sure what ailed the chief minister. People wondered if her condition was so bad as to make her stay in the hospital for more than a month, why wasn’t she taken abroad, to the US or Singapore, for advanced care?

Doctors from Britain, specialists from All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Delhi were all there, entering the hospital, coming by turns to give their opinion. One day, Dr Pratap Reddy made an unbelievable statement that Madam Jayalalithaa was fine and fully recovered and that she could go home any time she wanted; having said this, without much ado, he left for Hyderabad. Just two days later, he rushed back to Chennai when he heard Madam’s condition was critical.

It was 5 December 2016. Apollo Hospital officially announced that Jayalalithaa had had a cardiac arrest and had expired in the night. ‘It is with indescribable grief, we announce the sad demise of our esteemed honourable chief minister of Tamil Nadu at 11.30 p.m. today [5 December],’ said the statement released to the media after midnight.

A TV channel had taken the initiative to announce the death earlier in the evening. When did she actually die? Why should there be so much secrecy regarding the death of a chief minister?

In a bid to dispel rumours surrounding Jayalalithaa’s treatment and death, Dr Richard Beale, a UK-based consultant in intensive care medicine who was treating her, addressed a press conference in Chennai on 6 February 2017.1 He was accompanied by Dr Balaji, a government doctor, Dr Babu Abraham, critical care consultant, Apollo Hospitals, and Dr Sudha Seshaiyan, who had performed embalming on Jayalalithaa’s body.

‘Jayalalithaa had come to hospital with sepsis and was conscious,’ said Dr Beale, adding that she had co-morbidities and uncontrolled diabetes. Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body’s response to infection injures its own tissues and organs. Jayalalithaa was treated with non-invasive ventilation and she got better, the doctor said. But she was then put on ventilator, as her sepsis progressively got worse. ‘We had to give her sleeping medicines and she wasn’t able to communicate.’ He also said she was responding through sign language once she got a tracheostomy.

During the last hours, ‘as far as I am aware, she became short of breath quite rapidly,’ he said. He conceded that ‘she could have come [to the hospital] earlier’.

Dr Babu Abraham said, ‘When Jayalalithaa was admitted on the night of September 22, she was immediately given critical and supportive care.’ The diagnosis was ‘respiratory failure due to infection’.

A doctor working at Apollo Hospital attending to her also said off the record to a journalist that she was brought to the hospital too late.

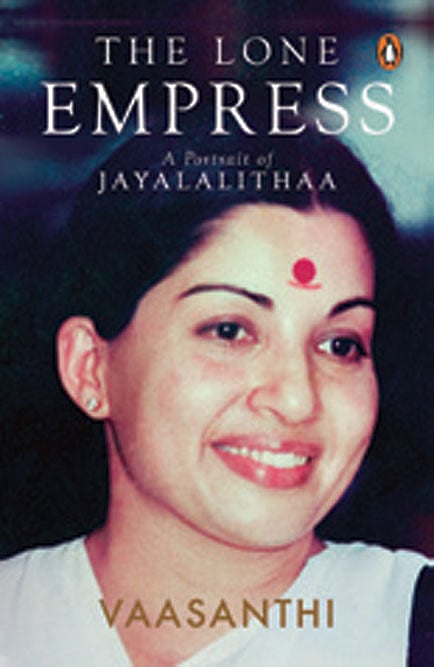

(This is an edited excerpt from Vaasanthi’s The Lone Empress: A Portrait of Jayalalithaa | Viking | 368 pages | Rs 599)