The Sage

At the age of 84, S Paul, the man who shaped Indian photojournalism, still takes his camera out for a daily shoot

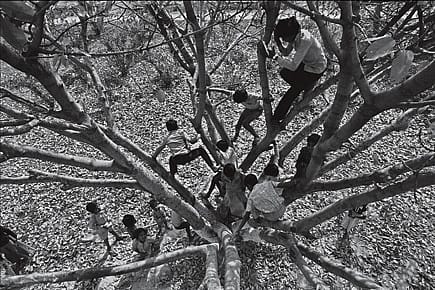

I first met S Paul in the darkroom of the Indian Express photo department. We were emptying drawers of film to make space for CDs. It was 2004. An undated photograph by him slipped out of the pages of a faded copy of Edward Steichen's curatorial masterpiece Family of Man. The photo, a newspaper clipping, showed children playing on a tree. Paul had climbed the tree and shot the children from its highest branch, inducing an illusion of their being afloat in space.

Our paths crossed again when I was coordinating entries for a Press Photo Contest. In the chalk white, tube-lit interiors of the Press Club in Bombay, I stared for a long time at his only entry: a black-and-white print of a woman carrying her baby in a basket on her head.

When I asked around about him, I got a few standard replies—' Oh, S Paul? He's a genius', 'He's a wizard', 'He's a master craftsman', 'He's Raghu Rai's elder brother', 'He's a recluse', 'He's actually way better than all of us put together'. Okay, has he done any books I can see? Nope. Any exhibitions? Nope. Does he teach somewhere? No idea. Have you seen any of his images? A handful, at best.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

If he's so good then why is so little known about him or his images? At the age of 84, Paul sahab, as he is called, is not only actively shooting every day but also winning contests by the dozen in almost every genre one can think of, from fashion to street life to birds.

A phone call led me to his eldest son Neeraj, who was not sure if his father would agree to be interviewed but asked me to send him my portfolio of photographs and writing. A few weeks later, Paul agreed to an interview.

When I arrived in Ghaziabad, where he lives, he was out shooting, giving me another day to gather information about him. A photographer at Hindustan Times told me he once saw Paul sahab shooting at the zoo. Another said he is the humblest man you could ever meet. A third asked innocently, "If S Paul and Raghu Rai are brothers, how are their surnames so different?"

It's 9.30 am. I'm waiting for him on the first floor of his two storey house in a white room, with purple and grey striped sofas and four photos on the wall. It's easy to spot the two that are his; I've seen one on his Facebook page and the other a few years ago at the India Art Fair. The other two are by his younger son Dheeraj.

From behind a sliding door he emerges, six feet tall, slender yet broad shouldered, with a camera slung on his left, and a copy of Open. He opens it to a picture I made. He likes it but feels it's a bit underexposed and could have been better. He's wearing a yellow Adidas sweater, grey trousers and black canvas loafers. He makes me shift into a chair facing the window, into the light, so he can see me clearly when he speaks. He then tells me the story of how he taught himself photography in a single day.

In the spring of 1951 in Shimla, while he was in his early twenties, disillusioned, bored working as a draftsman with the Indian Government's Central Power and Water Commission, he wondered what to do next. Directionless, he wandered outside and within. He remembered his long walks to school, during which he longed to take pictures with a camera. On 1 March of the same year, Paul bought a Carl Zeiss Nettar for Rs 275, a tripod for Rs 15, and a roll of Kodak 125 ASA film for a rupee and 14 annas. He purchased what he calls the "best book ever" on photography, The All-in-One Camera Book by WD Emanuel. At 11 pm, he made himself a cup of Nescafe and began his conversation with the book. At dawn, in the absence of a subject, he set the Nettar on a tripod, placed himself at distance of six feet, evaluated the exposure, and made his first ever set of images: 12 self portraits.

He later went to a photo studio, gave the roll for processing and waited. This was a time when exposure meters and auto focus didn't exist, and photographers spent sleepless nights until the results came in. The store manager, Chander Prakash, gave him a puzzled look and asked, "Since when are you a photographer?"

Paul replied, "Since last night. Why?"

Prakash handed over the prints to him and said, "Your photos are perfect."

Paul found solace in his newfound religion. His camera was an added limb, never out of his reach. He made pictures of his colleagues, his surroundings, his long walks along the snow-clad pathways of Shimla, of schoolchildren, of clouds, of trees, of mountains. He shot everything in sight.

In 1952, while walking around the ridge, Paul noticed a rare and poignant juxtaposition, a metaphor for the social dynamics of the new republic. Seated on the left end of a park bench was a distinguished-looking suited and hatted member of the British Raj, his right hand supporting his aged chin, his eyes firmly locked into the distance. On the right side was a mustachioed old man, almost the same age as the White man, dressed in a white kurta-pajama, his head in a turban, feet encased in mojris, wearing a shawl around his nervous frame—his eyes, too, locked in the same direction as the other's. Paul never made a print of this photograph; it was never shown to the public until he participated in a group show titled The Middle Age Spread in 2005. Paul says there are several such photos from his early days that he is yet to print, filed away neatly in his cupboards and his memory.

Paul was born in Jhang Maghiana, now in Pakistan, on 19 August—World Photography Day. A few days before his 16th birthday, two nations were created, and on the advice of their washerwoman, the Chowdhrys decided to cross an imaginary line in search of a new home. On the way, Paul saw policemen slamming their lathis on women's wrists to take away their belongings; he saw villages burning, death and misery all around.

After Partition, Paul's father found a job with the irrigation department in Jalandhar, while Paul followed his eldest brother B Pal Chowdhry who had found employment as an assistant superintendent in Shimla.

As a child, Paul was extremely shy and it prompted his grandfather to name him 'Sharampal'—the shy one. Years later, when Sharampal Chowdhry wanted to send his photographs for consideration to Miniature Camera World magazine, he altered his name to S Pal. For his second contribution he added a 'u', rechristening himself S Paul. Why? "Woh tabhi masti mein socha, thoda foreign type dikhta hai, toh kyun nahin (I'd thought in jest that it sounded a little foreign, so why not)".

Within a year of befriending the camera, Paul was invited by MM Chrishna, development commissioner with the Himachal Pradesh government, to set up a photo department to document government activities. In 1952, on a Friday of a month he can't recall, he showed up at their office, armed with his portfolio—stacks of international magazines in which his images had been published. The job was his in a matter of seconds.

A few years later, Paul was approached by the Northern Railway Headquarters to work as a photographer for them. He reached the interview with all his magazines in tow; it so uprooted the confidence of two other photographers that they left without being interviewed. A third remarked: "I will wait to congratulate you and go." Paul remained the chief photographer of the Northern Railway Headquarters for two years before applying for a month long leave in 1962.

Bored and eager for a bigger challenge, he gave himself a month to figure out what to do. On the last day of his leave, hating the idea of returning to the job, worried about his future because he had no new job in hand, the procrastination finally catching up with him, Paul began to panic. That very day, he received a telegram from Harry Miller, editor of The Indian Express, asking him if he'd like to join the paper as its chief photographer in Delhi—a job he would go on to hold for the next 26 years.

"When I took over the reins at The Indian Express," Paul says, "I ended up in direct conflict with a stringer named Amar Nath, who used to provide pictures of ribbon cutting and lamp lighting events by politicians to the paper. It was either those kinds of photos or a pictorial sunrise over some hills or a sunset by the sea that constituted newspaper photography. I hated that stagnant imagery and was dead set against it. I began pushing for images that fell in the genre of street photography." Paul promoted images of the daily lives of people and their interaction with their living and working spaces—what we now call 'offbeat', a 'stand-alone' or a photo- column; a photo that stands on its own in the paper, with or without a news angle, offering a pause to the reader.

Amar Nath quit after two years, leaving behind his darkroom assistant, 20-year-old Bhavan Singh, whom Paul meticulously tutored by taking him on his long and seemingly endless photo walks. Bhavan was soon promoted to photographer. RN Chopra joined a few months later.

Their immediate competitor was the Hindustan Times photo department, headed by Kishor Parekh. Parekh, who studied journalism in the US, had entered the profession a year before Paul and had already established a reputation as a fine photojournalist. It was Parekh who first insisted on providing a byline to photographs. Paul followed suit. Parekh and Paul held each other in high regard and were great friends off duty. Once, Parekh invited Paul and his younger brother Raghunath (Raghu Rai) to his home and served them whisky and beer cocktails. After a few drinks, Paul vomited. Parekh took him to a hospital opposite his house. In the morning, Parekh and Raghu went to visit Paul. On entering, Parekh asked Paul, "Kyun ladka hua ya ladki? (Is it a girl or a boy?)" They had admitted Paul to a maternity hospital.

The two were fierce opponents in the field. Paul once told Parekh: "You are a very dear friend and I respect you a lot, but as far as journalism [is] concerned, every photographer is my enemy!" A few years later, Parekh held an exhibition of his photographs of Jawaharlal Nehru. After waiting for days for 'Pole' to show up, Parekh finally called him: "I respect only one guy and he hasn't shown up for my exhibition yet." Paul did show up. Months later, he took a photograph of the Prime Minister bathed in dappled light, which prompted one more call from Parekh: "Pole, your one photo of Nehru killed all my images of him."

Every assignment Paul did was meticulously planned and executed. He would always reach an hour before any planned news event. Once, the heads of the Commonwealth states were visiting Delhi. Paul went to Vigyan Bhavan a day before and studied the dais, the lights and the arrangements. The next day, he reached an hour early, took the best spot in the photographer's pit and waited. When Indira Gandhi took the stage, he fired a few frames and then stood patiently while others around him were figuring out what exposure settings they should shoot. A few in the back rows passed their cameras requesting him to shoot for them. He obliged everyone. "While other newspapers carried a picture of Indira Gandhi lighting a lamp or the heads of state receiving bouquets or a group photo, my photograph stood out most," Paul says with pride, "All the heads of state lined up with folded hands offering a standing ovation to the Iron Lady as she stepped on to the dais."

He talks fondly of covering the Pakistan War, when he deserted the convoy of journalists and made his own set of images, which weren't sieved by the defence department. He remembers hiding in a small cabin at India Gate, waiting for the photojournalist Srinivasan to leave so he could finally step up to the ledge and take his memorable photograph of the Republic Day parade.

Paul's memory is racing ahead now. He speaks about that photograph of children playing on the branches of a tree in a park in Punjabi Bagh. He spotted them and quietly made his way to the top and balanced himself on two branches. An old Sardar out for a walk saw and yelled at him: "Je tu otthe gireya, taan teri haddiyan vi na milniyaan (If you fall, even your bones won't be found)." A child on the ground looked up and said "bhoot (ghost)!" And through his 20mm lens, Paul captured the universality of a child's sense of wonder.

Paul's self-worth, too, is legendary. While photographing former Prime Minister Morarji Desai, Paul requested the PM to move a little to the left into the light. The PM refused and told Paul to shoot him where he is and not to waste more film. Paul packed up and left immediately. When questioned by his editors on the absence of a photograph, he said, "The PM is saying I am wasting film, so I didn't waste any!"

Paul was not often seen in office, as he used all his spare time shooting for himself. He'd finish assignments and hand over his film to photographers from other papers, requesting them to take it to his office, while he fished out his personal camera and rolled away in his Fiat scouting for images.

"When I used to go shooting," Paul tells me later, "I used to carry not only my cameras and extra film but also my lunch, some old newspapers, a camera toolkit and a periscope." In his Fiat, purchased for Rs 22,500, Paul used to carry two spare tyres instead of one, a lesson he learnt after he had two flats on his way to Pushkar. His Fiat was smashed to bits by a mob while he was making his unforgettable photograph of patients and doctors standing on the balconies of AIIMS, watching Indira Gandhi's corpse leave the hospital. The photograph, he says, is well worth the loss. With no visual indicator of death, or the event, the photograph still shows the magnitude of the tragedy through those curious faces.

Once, legendary photographer Raghubir Singh, known for his quirky images of the Ambassador car, called Paul and told him about a foreigner on assignment in India. The man was looking for someone to represent and contribute to Magnum, a photo agency founded by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa and two of their friends. Raghubir had inside information that Paul was the man they'd like to meet and consider. On a rare evening when Paul entered his office, his colleagues informed him that a firang had called for him in his absence. Instead of reporting to work, Paul recalls, "Uss din na meri gaadi zoo ki taraf nikal padi thhi (that day, my car had just taken off toward the zoo)." Paul didn't regret missing the opportunity. "I knew that if I joined Magnum, I'd have to travel a lot and I don't like that."

The man he missed was George Rodger, who had been impressed by what he'd seen of Paul's work in the 1967 edition of the British Journal of Photography. He had called to make him an offer. Rodger was one of the founders of Magnum. The agency would eventually pick Paul's younger brother Raghunath Rai Chowdhry, better known as Raghu Rai.

In 62, when Paul was living by himself in Delhi's Defence Colony, he went home to meet his parents in Punjabi Bagh. Raghunath, his younger brother, had come home after concluding his temp job with the Indian Army in Ferozpur. Much like Paul a decade ago, Raghu did not know what to do. He asked his elder brother, "Mera kya hoga ab? (What will happen to me now)" Paul asked him to pack and come along.

It was Paul who gave Raghu Rai his name. Most photographers gossip that Paul is jealous of Rai and that bitterness is what keeps him aloof. Paul laughs it off and says, "No matter what people think or say, I am not jealous. Raghu is my student, and his success is my success too as a teacher, as an elder brother. What do they know about me and my equation with Raghu?" I ask him about the best photo book he's seen in recent times. "Raghu's book on Bombay," he responds.

I ask Neeraj a few questions about Paul's rigour of shooting daily. "See, we tell him he's got to take it slow, but he doesn't listen, so now we don't say anything. Baarish ho, garmi ho, ya Dilli ki thand (whether it's raining, hot, or Delhi's cold), nothing bothers him. He frankly makes me feel quite ashamed, because he shoots more regularly than Dheeraj and I." For Paul, missing a day of shooting is like a singer falling back six days if he misses a single day of riyaaz.

Through a sunless lane in West Vinod Nagar, Bhavan Singh's granddaughter guides me to their home. Bhavan and I are in his windowless first floor workspace, dotted with trophies of his tennis playing granddaughter. Wedged between her trophies is a faded bronze medallion. It's his World Press Photo prize, which he won for a photograph during the early years of the Bodo conflict in Assam. Just above the racks containing old transparencies hangs a frame aged in dust. I move closer to it; he asks me to wait, and wipes off the dust with his fingers. It's his photo of a rifle lying unattended on the floor during Diwali at Red Fort, surrounded by rain puddles with two pigeons sitting on its spine stock. A perfect metaphor of war and peace, simple, subtle and evocative.

"This is what I learnt from Paul," he says, "this looking beyond the mundane ribbon-cutting and lamp-lighting photos. Before Paul, I was a man working purely for a livelihood; it was he who made us all think beyond the obvious."

"I remember a picture of Paul's, a man shaving near the railway tracks in Shimla. His pictures have a unique sensitivity that makes you connect with his subjects in an instant. His timing is impeccable, his technique flawless, but he believes in luck, and luck has always been on his good side. He brought in all these human elements in his pictorial style and merged it with newspaper photography to create his own unique signature which we have all borrowed from heavily over the years."

Before I went looking for Paul, Akella Srinivas, a Bombay- based photographer tells me nothing remains the same after one has been touched by an S Paul photograph. His vision influences your vision. One starts to see the world around very minutely, you appreciate the beauty of things a lot more than before. Srinivas finds it hard to see a dove the same way he used to before seeing Paul's version of the bird in flight, all its feathers on display, its wings converging like a namaste, a dancer invoking the gods before a performance.

The following day, Paul is dressed in a maroon shirt, beige trousers, and the same black canvas loafers. In his early days he used to wear a suit to his assignments. It took a while for the Raj to leave him. Before we head out, I ask about the self portraits he made on the morning of 2 March 1951— they were lost forever to termites when he moved to Delhi.

Paul and I are walking through the lanes of Surya Nagar. He walks from lane to lane, skirting the side of the road, his eyes moving around like a radar, greeting neighbours with his camera wedged between his palms as he says "Namaste!" He stops to take pictures of a cow. The cow abandons what she's doing and looks straight at Paul who commands her, "Chal tu apna kaam kar na (Come on, just do your own thing)." She turns away for a second, then resumes staring at Paul. "Arre, phir wohi baat (Oh, not that again)," he says. She relents and the standoff ends.

Paul loves taking pictures of trees. A few months ago, he aimed his lens skyward and isolated two tree tops in his frame; the resulting image gives the impression that the tree on the left is a human face whispering into the widespread branches of the other.

Raghu Rai's office is on the fourth floor of a darkened beige building in Mehrauli, flanked by Sant Nirankari Satsang Bhavan on one side, and cows and a dargah on the other. Rai is seated on one of two maroon office chairs placed on a flattened cardboard box. His feet are not yet inside his electrifyingly shiny leather loafers. He tells me the office is bare because they are moving to another workspace soon. He summons his help to bring in a table. Minutes later, he comes in with a cardboard box and plywood shelf.

Rai is of the view that there are three kinds of photographs. The first kind is pretty photographs, loaded with colour imbalances, off key saturation and regular visual tropes. The second is when photographers ape global trends and junk their own voice. The third is the most honest, and hence difficult— photography that is guided by one's soul. "A lot of the work I see today is either pretty or trendy; there's no soul in any of it."

According to Paul, he came into photojournalism at a time when "na kuch naya ho raha tha, aur na kisiko kuch naya karne ki chaah thhi (nothing new was happening, nor did anyone have the desire to do something new)." In the company of Paul, the novice Raghu was exposed to an entire gamut of magazines, photographers and camera equipment. He was a full-time assistant to him, processing his film, making contact prints; often, the brothers cooked for each other.

Paul's friend Yogjoy, a landowner, was heading to Rohtak to check on his property, and on Paul's insistence, Rai tagged along with him. Paul loaded him a roll on an Agfa Super Select and when Rai was back, Paul reviewed his pictures. Rai had no responsibilities at that time, so no liabilities either. His pictures were laced with this sense of freedom. Paul sent one of them to The Sunday Times in London to be considered for its weekly photo column. It was published, and the money Rai earned from that one photograph lasted him an entire month. He bought himself more film. Much like Paul, he too had stumbled and found his religion. Paul jokes that he had made a photographer out of an ass; Rai's photo had been of a playful little donkey.

Gaining confidence, Rai asked Paul if he should try to get a job somewhere. Paul wasn't sure if he was ready but sent him across to Parekh who took on Rai—on probation for a month. In Paul's words, Raghu had tasted blood and was in a tearing rush to reach the top but his foundation was still very weak. Some months later, Rai moved out. "I had to chart my own way," Rai explains, "plus bhaisaab was getting married and he needed his space too." After almost a year in HT, Rai moved to The Statesman, and then Sunday Magazine, and finally India Today where he worked with Paul's old friend Bhavan Singh.

"I am a product of two giants," Rai says, "Paul and Parekh. And when one is between two giants, you either get crushed or, like me, you bounce. I came to realise very early, no one is waiting for you in this profession. Jo bhi hai so ab hai, yaheen hai (Whatever there is, it is now, here)."

Paul, in Rai's view is a very shy, docile person sense of who is content being in his own comfort zone. His extreme 'moh' for his family prevented him from exploring other regions of the country.

During my conversation with Rai, I present to him a thought that has been on my mind since I met Paul. What if the two of you were to reconcile and co-author a book? 'Delhi: a Portrait by S Paul and Raghu Rai' or 'S Paul and Raghu Rai's India' or 'Trees by S Paul and Raghu Rai'. Rai's chin is resting on his right hand and his gaze is fixed past the Qutub Minar. His attention wanders back to me. He smiles and says, "I have done my best, I have tried very hard to get through to him, but…"

Paul's aloofness is usually misunderstood for arrogance and his frank opinions are often dismissed as downright rude. He stays away from cliques and is of the opinion that after the arrival of digital cameras, we are no longer photographers, but image-makers.

"Today's photojournalists," he feels, "have no clue of global trends. They don't evolve and are stuck in one mould and that's dangerous. There is barely anyone whose photos have any social context to them. The fine craft of making a photograph that stands the test of time is absent. It's all fast food now; ironically, a lot like 1962."

With a Gurgaon-sized lump in my throat, I ask: "What about cellphone photography and instagram?"

"Disgusting," he says. "It's nothing but hellphone photography."

This sentiment is echoed by Kishor Parekh's mop-haired son, Swapan. Seated on a bean bag in his yellow-walled studio in Mumbai, Swapan is the only bridge between the masters and the newer lot. He put Paul's tips to use while covering the Latur earthquake, and a photo shot at high noon, with his flash, got him a World Press Photo prize. "When exposed to new equipment, Paul sahab is like a beast waiting to tame and devour it," says Junior Parekh.

Swapan feels that Paul has the luxury of coming out to the world the way he wants. "With the right edit that brings out not just the best, but the greatest of S Paul, he can be perceived and remembered not just as a pictorialist or a landscape photographer or a photojournalist, but as a true modernist. His work has great sanctity. It's a masterclass in everything that photography stands for and for the future growth of photography; for it to grow beyond its current shoot and delete style, Paul sahab must make the full gamut of his work publicly known."

I ask Paul about his Facebook page. For an artist who has shunned the spotlight for decades, how did he agree to have his work so widely displayed? "Oh, my son Dheeraj did that without my consent. They keep telling me to do a book, or an exhibition and I have not gotten around to doing one yet. I did my first and only exhibition at Max Mueller Bhavan, Delhi in 1991—the first Indian photographer to be invited to do so, you know!" The exhibition then travelled to three other cities in Germany and his photos were sold at record rates, with visitors requesting reprints by the dozen. He was forced to turn down many people because he couldn't cope with the pressure. It's evident that he likes the 'Likes' his photos get on Facebook. "It's nice to be appreciated," he says, "people share my photos, word gets around and youngsters ask questions, achcha lagta hai (it feels nice)!"

Legend had it Paul has enough work to produce a book a month if he were to dip into his mammoth archive and pick 100 images at random. When will we see that happening? He lets out a hearty laugh: "Aadmi hi khud ka dushman hota hai (A man is his own enemy)." He opens a tiny 2010 Roli Books catalogue to page 37. It lists an untitled retrospective of S Paul, soft cover, 128 pages, to be released sometime in the future. Paul hasn't gotten around to finalising the 100-odd images yet. He can't figure out which ones to show from his hundreds of thousands of negatives, prints, transparencies and now, digital images.

In 2004, B&W magazine called Paul the Henri Cartier-Bresson of India, a title he says he probably doesn't deserve. He'd be happy just to be known as the S Paul of India. "What HCB did, he did at a time when the odds were mightily stocked up against him. Slow films, bigger cameras, no exposure meters, auto focus or 16 GB memory cards and motor drives like today." Bresson, according to him, is the most copied photographer of our times, but never equalled.

Paul is perplexed all of a sudden; I ask why. He says all his memory cards are full. "Dheeraj is busy and has no time to download my images, and my assistant has a court case on, so he's on leave too. But I need to go and shoot tomorrow, too, so I will have to buy new memory cards," he says. He wishes to travel to Lansdowne. "I have some pictures in my mind that I want to make."

Paul sahab, one last question before we go: what will happen to all those photos you have shot today? His smile puffs his shrivelled jawline as he looks skywards and says, "Ab aagey, bas, infinity!"