The Man and the Mahatma

JAMES BOSWELL'S LEGENDARY biography of Samuel Johnson was based on first-hand experience of living, working and travelling with the great man for most of his life. Ramachandra Guha, denied that privilege, has done the next best thing—immersing himself for a decade in virtually everything Gandhi ever wrote or said and most of what other people wrote or said about him. What emerges in both massive volumes of this magisterial work is the most detailed account of Gandhi's life ever written, though there have of course been several others. Among the archives Guha has trawled was an unexpected and previously untapped treasure trove of Gandhi papers at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library.

Did Gandhi really change the world, as the subtitle of this book—Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World 1914-1948 (Allen Lane; 1,152 pages; Rs 999)—suggests? Guha's own very emotional attachment to his subject is palpable, but he is too honest a historian to ignore evidence to the contrary. He prefaces this book with three contrasting views of his hero. The first in adulation, by Albert Einstein, proclaims: "Generations to come…will scarce believe that such a one as this even in flesh and blood walked upon this earth." The cynical second, by the Viceroy Lord Willingdon, who had to negotiate with Gandhi the politician, described him as "a perfect nuisance" and "the biggest humbug alive". The third, from Gandhi himself, made a virtue of his own inconsistencies, being "true to myself from moment to moment" and making "no hobgoblin of consistency". All three opinions figure prominently in the narrative that follows.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The arena in which Gandhi's inconsistency figured most prominently, and which continues to bedevil us today, was his battle against caste prejudice and untouchability. Guha reminds us that the 1915 manifesto of Gandhi's ashram endorsed caste taboos and declared: 'There is no reason to believe that eating in company promotes brotherhood ever so slightly.' Later, in 1920, Gandhi wrote about caste restrictions as being conducive to discipline and self-control, advocated reforming the caste system rather than abolishing it, getting rid of untouchability but retaining segregation and opposing campaigns for temple entry by his so-called 'Harijans'.

As late as 1935, commenting on a village dispute over access to the local school, Gandhi advised persecuted Harijans to migrate, rather than fight for change. "If people migrate in search of employment," he remarked, "how much more should they do so in search of self-respect." This was precisely the sort of patronising advice that the Dalit leader BR Ambedkar was committed to fighting, and his rivalry with Gandhi forms a major strand of this biography.

Ambedkar rightly regarded the Congress as an overwhelmingly upper-caste party and made no bones about preferring British rule to that of the Congress. Throughout the constitutional negotiations of the 1930s and 40s, his key demand was for reservation of a fair proportion of seats in legislatures for what were then called the 'Depressed Classes', to be filled by separate electorates of the 'Depressed' themselves. Gandhi and the Congress clung equally fiercely to the notion that the 'Depressed' were part of the wider Hindu community and not a separate minority entitled to separate electorates. When the Raj granted Ambedkar's demand for separate electorates in its Communal Award of 1932, Gandhi embarked on a fast-unto-death in protest. Faced with the prospect of widespread anti-Dalit violence if Gandhi died, Ambedkar gave in to what he considered the most blatant emotional blackmail by his wily opponent.

Guha is scrupulously fair in his account of Gandhi's long-running conflict with Ambedkar. Although Ambedkar lost the constitutional battle for separate electorates, he did succeed, through pressure and persuasion, in radicalising Gandhi's own attitudes to caste. By the 1940s, Gandhi had become a champion of temple entry for 'Harijans' and was even accepting inter-caste marriage. He had initially forbidden a proposed love-match between his own Bania son and the Brahmin daughter of his close colleague C Rajagopalachari (Rajaji). After forcing the young couple to observe a five-year ban on any contact between them, he eventually relented and permitted the match.

Gandhi was even more hostile to inter-marriage across the Hindu-Muslim communal divide. He forbade his son Manilal, based in South Africa, from contemplating a love-match with a Muslim woman, even though the latter was willing to convert to Hinduism. Gandhi's motives were as much political as personal, since he feared a Muslim backlash if the girl converted and Hindu outrage if she didn't. Guha reminds us of a similar dilemma when Jawaharlal Nehru's sister Vijayalakshmi eloped with a Muslim journalist. The poor young woman was hauled back to Gandhi's ashram, where she was bullied into renouncing her Muslim lover and accepting an arranged marriage to a fellow Brahmin.

As with the Gandhi-Ambedkar relationship, this book is remarkably even-handed in its appraisal of Gandhi's equally tempestuous and politically damaging rivalry with the Muslim leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Guha traces this back to a public meeting they both addressed in 1917, when Gandhi forced the anglicised Jinnah to speak in his halting Gujarati and then rather patronisingly and publicly advised him to practise speaking in his mother tongue if he wanted to appeal to the masses.

At the same meeting, Gandhi teased the veteran leader Lokmanya Tilak for his unpunctuality. Referring to Tilak's famous slogan of Swaraj being his birthright, Gandhi quipped: "If one does not mind arriving late by three-quarters of an hour at a conference summoned for the purpose, one should not mind if Swaraj comes correspondingly late."

It was the sort of joke that could both amuse and irritate. One of the things that most endeared Gandhi to my father, Minoo Masani, was the old man's mischievous sense of humour. Guha records the fact that my father, then one of the founder-leaders of the Congress Socialist Party, visited Gandhi in 1934 to persuade him not to condemn the infant party's radical manifesto. He was received with disarming, avuncular warmth. Commenting on the socialist proposal for nationalisation of the means of production, Gandhi joked: "Rabindranath Tagore is an instrument of marvellous production. I do not know that he will submit to being nationalised."

On a more serious note, Guha reminds us that Gandhi's relationship with Tagore was a friendship of equals with frequent and heated disagreements. One such falling-out in 1921 was about Gandhi's attack on English-medium education and his assertion that leaders like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Tilak would have been greater reformers "if they had not to start with the handicap of having to think in English". Tagore protested against "this blind zeal for crying down our modern education", accused Gandhi of "a dangerous form of egotism" and insisted that Roy "could be perfectly natural in his acceptance of the West". "The whole world is suffering today from the cult of selfish and short-sighted nationalism," Tagore admonished Gandhi. India, he said, had welcomed and assimilated foreign invaders throughout its history and should now do likewise with the West.

For similar reasons, Tagore condemned Gandhi's Swadeshi movement, and especially its burning of foreign cloth, a form of destruction the poet thought incompatible with true non-violence. Guha does not mention this clash over Swadeshi, though he does tell us how Tagore lamented Gandhi's description of the Bihar earthquake of 1934 as "divine chastisement" for the great sin of untouchability. Tagore publicly condemned such obscurantism when "this kind of unscientific view of things is too readily accepted by a large section of our countrymen".

THIS BIOGRAPHY MAKES no attempt to conceal or extenuate Gandhi's less rational fads, phobias and obsessions. Closely related to Swadeshi was his campaign for hand-spinning, seen as both a form of personal discipline and a rejoinder to economic competition from machine-made cloth. Despite the opposition of stalwarts like Motilal Nehru and CR Das, Gandhi narrowly secured the passing of a Congress resolution making it mandatory for all its office-bearers to spin for at least half an hour a day and send the newly established Khadi Board at least 1.8 kg of well-spun yarn each month.

It was a rule which prompted Annie Besant, the grand old lady of the Congress, to call for the party to be rescued "from being strangled by Gandhi's yarn". But Gandhi was impervious and saw no absurdity in writing to Lady Lloyd, wife of the Governor of Bombay, offering to send her a spinning-wheel and a tutor to teach her how to use it.

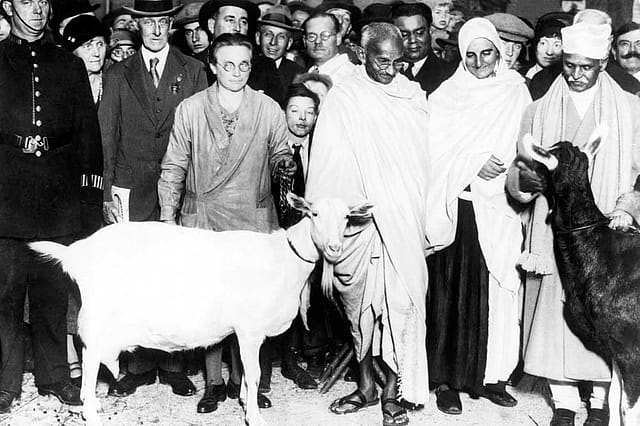

Another example of Gandhi's faddism was his insistence on drinking only goat's milk and travelling with his own goat to make this possible. It was one of the many fads which prompted the witty poet-politician Sarojini Naidu to remark: "It costs a great deal to keep Bapu in poverty," a joke which Guha does not mention. But he does give us the anecdote about how Gandhi swore to give up milk, was then advised to drink it during an illness, so announced that his oath was only intended to apply to cow's milk, thus allowing him to drink goat's milk instead. "It seems to be wholly illogical," commented his old South African friend, Henry Polak, "but I prefer his lack of logic and his life to his logic and his death. In any case, his vow was illogical, and as two negatives make an affirmative, I am perfectly satisfied with the result."

Gandhi's insistence on goat's milk prompted the possibly apocryphal story, which Guha does not mention, of Gandhi's goat Nirmala accompanying him on the ocean liner that took him to London in 1932 for the Round Table Conference on India's constitutional future. Photos in the British press showed him flanked by a nanny goat on one side and on the other his inseparable, British disciple Mira Behn (born Madeleine Slade), draped in a khaddar blanket. It was an image which prompted this rude limerick (which Guha, alas, never mentions):

There was an old man called Gandy

Woke up in the night feeling randy.

He rang for the maid,

Said 'Go fetch Miss Slade

Or the goat if she's not handy'

Gandhi's strange attitudes to sexuality had by this time given rise to widespread accusations of both fanaticism and hypocrisy, which Guha clinically documents without any prurience. Gandhi's imposition of brahmacharya or celibacy on himself and all his ashramites is well known, as also his penchant for sleeping naked with young women to test his own self-control. Less familiar is his obsession with conserving the male 'vital fluid' and stigmatising not only masturbation but spontaneous emissions. Guha quotes several excerpts from Gandhi's letters to young men on the subject, and also Gandhi's own crisis of conscience when he woke up one morning with an erection and masturbated, a lapse he then surprisingly chose to share with his female disciples.

We also hear throughout this period of Gandhi's very passionate but platonic relationship with a Bengali lady, Saraladevi Chaudhrani, whom he espoused as his 'spiritual wife', although Rajaji wisely persuaded him not to make this public. Guha makes no excuses for Gandhi's misogynistic attacks on modern women for what he considered their exhibitionism in dressing up and seeking to attract men. His opposition to contraception was also extraordinary in advising women to resist sex with their husbands instead of using protection.

Guha tells us that he was moved to tears when reading the court judgment sentencing Gandhi to his first term of imprisonment during the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1922. Despite his own nationalist sympathies, Guha is balanced and objective in his treatment of Gandhi's relationship with the Raj. Gandhi once wrote: 'No European nation is more amenable to the pressure of moral force than the British.' This belief was the bedrock of his aims and methods during the half century leading up to independence.

Unfortunately, the lack of consistency which he claimed as a virtue was also his undoing, even though much of it was inspired more by political expediency than by moral principles. Gandhi loyally supported the imperial war effort in World War 1. In 1919, even after the Jallianwalla massacre, he advocated cooperation with the Montagu- Chelmsford constitutional reforms, arguing that half a loaf was better than none. But only a year later, he changed his mind and committed the Congress to non-cooperation, in the teeth of opposition from other leaders like Jinnah, Madan Mohan Malaviya and Annie Besant, who were booed and barracked when they spoke against him.

When it came to Muslim separatism, Guha shows how Gandhi created his own pan-Islamic nemesis by backing the Khilafat agitation to restore the Ottoman caliphate which Turkish secularists had themselves abolished. The religious revivalism of Khilafat, added to Gandhi's own acceptance of Hindu mahatmahood, alienated younger, modernising and secularist Muslims like Jinnah, who increasingly felt, like Ambedkar, that they had more in common with the Raj than with Congress.

Guha rightly argues that Gandhi was outgunned and outmanoeuvred at the Round Table Conference of 1932. He had insisted on going as the sole Congress representative to the conference, where he failed to overcome the resistance of formidable opponents like Jinnah, Ambedkar and the Nawab of Bhopal to the Congress demand for a majoritarian, centralised state. Surprisingly, Guha's very detailed account of Gandhi's London stay makes no mention of his much-publicised debate with the eminent educationist Sir Philip Hartog, a former vice-chancellor of Dacca University and founder of the London School of Oriental & African Studies. Gandhi had used a speech at the think-tank, Chatham House, for a diatribe against English-medium education, but Sir Philip took up the challenge and successfully flawed Gandhi's arguments with hard statistics on growing literacy under the Raj.

The political compromise that emerged, despite Gandhi, in the new 1935 constitution and the 1937 elections resulted in strong, autonomous provinces, with democratically elected governments, which might, given time, have evolved into a loose federation at the Centre. Although Gandhi allowed Congress ministries to take office in the provinces where they had won, the outbreak of World War II proved a major setback to further constitutional progress. Congress ministries resigned in protest at not being consulted about India's entry into the war, and the stage was set for a six-year confrontation between the Congress and the Raj, with the Muslim League as its chief beneficiary.

Based on Guha's account of Gandhi's wartime policies and activities, there can be little doubt that he bears the chief responsibility for the breakdown of Congress relations with successive viceroys and with Churchill's War Cabinet in London. Gandhi's own sympathies, as in World War 1, were with the British, and he was genuinely distressed by German bombing of London, a city of which he had fond memories. He insisted that he was not pro-Japanese on grounds of Asian solidarity. Nevertheless, he made what Guha calls 'spectacularly ill-judged' appeals to the British to lay down their arms and instead offer satyagraha to the advancing Germans. Gandhi had already met and praised the Italian Fascist dictator Mussolini on his visit to Rome in 1932. Now he declared that even Hitler was "not as bad as he is portrayed" and offered to go visit him in Germany to sue for peace. As against British appeals, Gandhi called on the US to remain neutral, even after Pearl Harbor. Not surprising then that even those elements of the British left most sympathetic to Indian independence thought Gandhi's wartime interventions perverse and eccentric, if not downright treasonable at a time when Britain's very survival was in doubt.

In March 1942, the War Cabinet sent out a mission led by the Labour politician Stafford Cripps to negotiate with Congress. Cripps offered immediate Congress participation in the central government, followed by Dominion Status at the end of the war. But Gandhi insisted on immediate, full independence, even though he had previously seen no difference between independence and Dominion Status, as enjoyed by Canada and Australia.

Cripps returned to London empty-handed, while Gandhi made a quixotic appeal to Britain to withdraw unilaterally from India and leave it to make its own peace with the Axis powers. A few months later, in August 1942, he led the Congress decision to launch the Quit India movement, against the better judgement of colleagues like Nehru and Rajaji.

AMBEDKAR CALLED THE Congress' return to civil disobedience "a game of treachery to India" and joined the Viceroy's Cabinet. Jinnah said much the same, and the Muslim League backed the war effort and capitalised on the absence of the Congress leadership in prison. Gandhi spent most of the war years under nominal arrest, though accommodated in great comfort with his entire staff at the Aga Khan Palace in Poona. Although the Quit India movement involved a considerable amount of violence, including cutting of phone and telegraph lines, sabotage of railways and attacks on public buildings, Gandhi turned a blind eye and failed to call off the movement as he had in 1922. Instead, he went on a three -week fast to protest against government propaganda.

The British press had long seen these fasts as a form of blackmail, 'substituting suicide for discussion'. Now both Ambedkar in Delhi and Prime Minister Churchill in London were suspicious that Gandhi was secretly receiving glucose from the doctors attending on him. "It now seems certain," Churchill lamented, "that the old rascal will emerge all the better from his so-called fast."

Guha cites a Delhi dinner party given by my grandfather as evidence of how even families were divided over Gandhi's fast. My maternal grandfather, Sir Jwala Prasad Srivastava, Civil Defence Member of the Viceroy's Cabinet, was hosting a party for 100 guests at the Imperial Hotel in honour of the British Governor of UP. He informed his guests that his wife, Lady Kailash, and his daughter (my mother Shakuntala) were boycotting the dinner in solidarity with the fasting Mahatma.

Might India have got its independence without Partition if Gandhi and the Congress had accepted the Cripps proposals or the later British Cabinet Mission Plan for a loose federation with safeguards for minorities? Should Gandhi have accepted the advice offered to him by the eminent Muslim educationist (and later Indian President), Zakir Husain, to take the wind out of Jinnah's sails by conceding all his demands for Muslim representation? Guha considers that these are counterfactuals and not the job of a biographer to answer. But to my mind, they do bear directly on Gandhi's statesmanship and demand considered historical judgements based on the best evidence.

Guha takes issue with Arundhati Roy for her characterisation of Gandhi as 'a saint of the status quo', but he cannot deny that the Gandhian approach to untouchability has left caste prejudice stronger than ever, with an estimated 30 per cent of Hindus still practising untouchability today. Guha's claims for Gandhi as the father of Indian democracy and also of non-violent protest movements across the globe are tenuous to say the least. Arguably, Indian democracy owes more to liberal politicians like Tej Bahadur Sapru and Srinivasa Sastri, who cooperated with the embryonic parliamentary institutions that the Raj introduced in 1919 and 1937. And surely passive resistance as a political technique is as old as mankind, dating back to the Buddha and Christ, both of whom Gandhi much admired, and more recently to 19th century British Chartists and trade unionists.

Guha is on stronger ground in his praise of Gandhi's commitment to truth and openness. But he underestimates Gandhi's use of guile in destroying political opponents like Subhas Bose. In 1939, when Bose won election as Congress president and defeated Gandhi's candidate, the Mahatma publicly professed to accept the democratic verdict while quietly engineering the collective resignation of almost the entire Congress Working Committee, thereby making Bose's position untenable.

This biography focuses far more on Gandhi's relations with opponents like Ambedkar and Jinnah than with his own favourite protégé, Jawaharlal Nehru. Perhaps that's justified by the Nehru-Gandhi relationship having been so extensively covered elsewhere. Guha rightly emphasises the oft-neglected role of Rajaji as mentor, friend and critic of Gandhi and of Mahadev Desai, not merely as his secretary but as an outspoken and intelligent friend and advisor.

On a more personal note, this book is full of entertaining and often surprising vignettes. So we read of Rajaji's disapproval when Gandhi stopped wearing a shirt, and later of the decision of Pope Pius XI not to receive Gandhi in audience because of his scanty attire. We discover that Gandhi's prison reading included British schoolboy classics like Tom Brown's School Days and Kipling's Jungle Book. We hear that his ahimsa allowed the killing of stray dogs and invasive monkeys, to the horror of many Jains. The Congress volunteer band mistakenly and hilariously struck up God Save the King at the start of the fateful Dandi salt march. We learn that Gandhi wanted to turn the Congress from a political party into a social service organisation after independence, making way for a two- party system. And finally, there is the poignant detail of a veteran Gandhian bathing his murdered leader's corpse. "Bapu never took a cold bath," he reminisced. "How could I pour this icy water on his body?… A cry burst forth from my despairing heart…"

If there is a fault in this volume, it's the fact that it weighs in at over 1,000 pages. While this makes it a valuable resource for Gandhi devotees and for historians like myself, it will deter the more casual lay reader. That's a pity, because it's extremely well written, as one has come to expect from Guha, and both illuminating and entertaining. Some ruthless culling, especially of long and repetitive quotes from the many flattering letters and speeches of felicitation to Gandhi, would have made it a more manageable read.