A New Sharif in Islamabad

The Pakistani prime minister will continue to be the army’s tenant

C Christine Fair

C Christine Fair

C Christine Fair

C Christine Fair

|

15 Apr, 2022

|

15 Apr, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Sharif1.jpg)

Pakistan Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif addresses the National Assembly in Islamabad on April 11, 2022 (Photo: AP)

AFTER THE SUPREME COURT foiled a bid by former Prime Minister Imran Khan to scuffle a no-confidence vote, the variegated coalition of the opposition succeeded with 174 members out of 342 voting in favour of the motion. Imran Khan, the 69-year old former cricketer who opportunistically embraced the public trappings of Islamism and anti-Western vitriol, became the most recent prime minister to depart the official residence prior to completing his full turn. In fact, no prime minister has ever served out his or her full term in the country’s 70-year-old sordid dalliances with democracy. Imran Khan is the most recent prime minister to be reminded of the basic fact that the country’s official prime ministerial residence is a rental unit and the landlord is Pakistan’s seemingly omnipotent army chief. And for those who enjoy a bit of schadenfreude, the army is getting the rare reminder that not all of its tenants leave pleasantly or without causing a ruckus after doing so.

DEMOCRACY IS THE ARMY’S QUARRY

Pakistan’s first popularly elected prime minister was Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. He came to power as a result of the 1970-71 elections which ultimately precipitated the vivisection of Pakistan as the Western Pakistan elites could not tolerate a national assembly dominated by the Bengalis and their Awami League and centred in East Pakistan. After the loss of East Pakistan, Bhutto became the first civilian martial law administrator, then president and eventually prime minister. Even though Bhutto was himself a chief hindrance to any political resolution along with General Yahya Khan, the army was and is most vilified for the loss of East Pakistan. Bhutto capitalised upon the army’s ignominy. He pursued a nuclear weapons programme with verve, and he built up Pakistan’s armed forces in hopes of staving off discontent in the barracks. He made egregious concessions to Islamists in hopes of co-opting them. He abused his power like any autocrat and established a private security organisation to bust heads when the army refused. He pandered to the masses with his slogan of “roti, kapra aur makaan (food, clothes and housing)”. He began the jihad in Afghanistan in 1973 by exploiting Islamist Afghans who fled Mohammad Doud’s reprisal and regrouped in Pakistan. In 1973, he launched a brutal army operation in Balochistan which resulted in thousands of civilian casualties. Then in 1977, he rigged elections to ensure another term. As violence engulfed the country, General Zia-ul-Haq—the very army chief Bhutto appointed—deposed him in a coup. Bhutto was tried and convicted for the murder of a political opponent and went to the gallows.

Zia assumed the presidency and introduced many controversial constitutional provisions, such as the odious Eighth Amendment and its Article 582b which empowered the president to dissolve the National Assembly as well as various initiatives to render Pakistan a Sunni Islamist state. Under domestic and international pressure to hold elections, Zia announced his intention to hold a general election on a non-partisan basis. He identified three potential prime ministers—all from Sindh. Of the three, he selected Muhammad Khan Junejo. Zia’s amendments to Pakistan’s constitution had weakened the powers of the prime minister, bolstering Zia’s confidence that Junejo would do his bidding. But Junejo infuriated Zia by demanding the end of martial law, refusing to let parliament rubber-stamp Zia’s various ordinances, and signing the Geneva Accords in April of 1988, thus ending the conflict in Afghanistan without emplacing a jihadist government after the Soviet departure. After receiving the last tranche of American assistance, in May of 1988 Zia dissolved parliament and dismissed Junejo. Zia died in a plane accident in August of that year.

This coalition is a dog’s breakfast of partners who have nothing in common other than their desire to replace Imran Khan. Shehbaz Sharif inherits a derelict economy with ever-growing inflation and unemployment. With Russia’s war in Ukraine likely to go on, price pressure on oil and gas is likely to increase. The new government will likely have to reverse Khan’s populist subsidies which will not be popular. Under the best of circumstances, righting this economic ship would have been hard

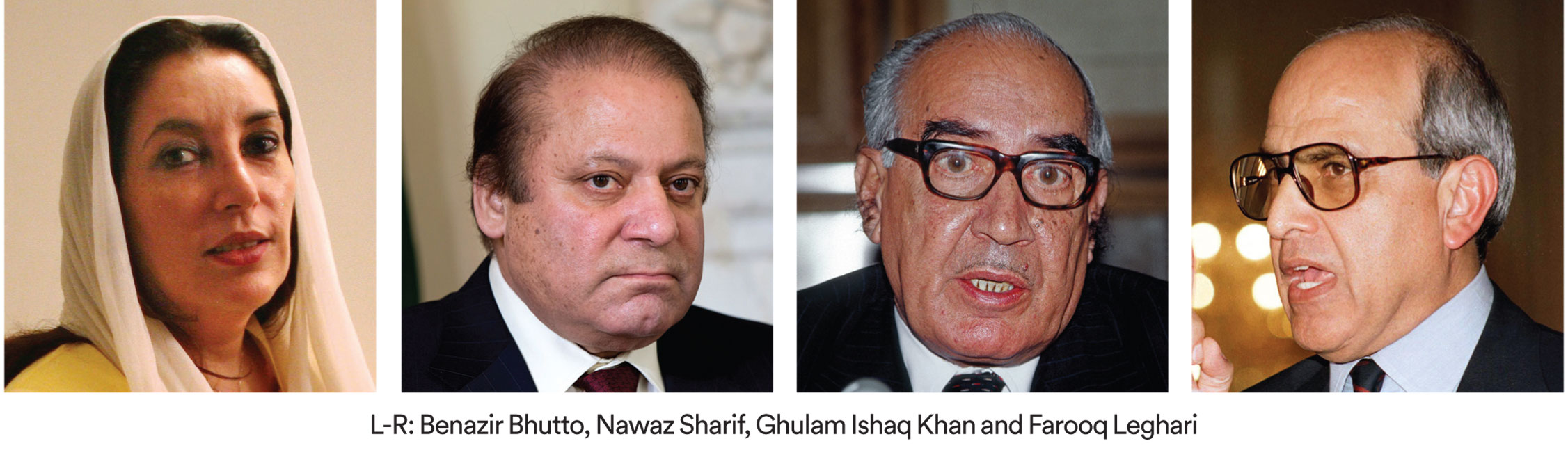

Democracy returned in November 1988 when elections were held. The primary contestants were Benazir Bhutto and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), founded by her father Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, and Nawaz Sharif, who headed the Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI) which was a coalition of nine parties comprised of supporters of Zia-ul-Haq and enjoyed the support of Pakistan’s intelligence agencies. Given Sharif’s ongoing conflict with Pakistan’s army, people may forget that Nawaz Sharif was himself a creation of Zia. Despite the support of the army and the intelligence services, Bhutto’s party won 94 of the 207 seats in the National Assembly. IJI came in second with 56. Turnout for this election was a meagre 43 per cent. PPP formed a governing coalition with other ostensibly leftwing parties and Bhutto became prime minister. However, she became the prime minister with a caveat. The army acquiesced in her tenure provided she did not interfere in military affairs or foreign policy. These would be the terms confronting every prime minister since and those prime ministers who reneged on this commitment quickly found their governments dismissed.

After a mere 20 months, President Ghulam Ishaq Khan invoked the Eighth Amendment and prorogued parliament citing misgovernance and industrial-strength corruption.

Following elections in 1990, Sharif became prime minister. However, Ghulam Ishaq Khan again invoked the Eighth Amendment three years later. While the Supreme Court overturned this dismissal, both men resigned in 1993 due to the unending mayhem. Bhutto again became prime minister following fresh elections in 1993. However, citing corruption and incompetence, President Farooq Leghari—whom she personally selected, presuming him to be loyal—invoked the Eighth Amendment and prorogued parliament. Troops surrounded her home and her husband Asif Ali Zardari (aka “Mr Ten Percent”) was arrested as he tried to leave for Dubai. He was convicted of various crimes and was in prison until 2004.

Elections were held in 1997 and Nawaz Sharif and his party, the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), won an overwhelming majority. Sharif, despite being a creature of the Pakistan army, believed that his electoral mandate bequeathed to him the actual powers of prime minister inscribed in Pakistan’s constitution. And Sharif was clearly delusional. In October 1998, Sharif sacked a popular army chief, General Jehangir Karamat. The army readied itself to step in; however, Karamat believed in democratic processes and did much to promote democracy in the country. Accepting that it was in fact the prerogative of the prime minister to dismiss and appoint the army chief, he acquiesced. To this day, many in the Pakistan army revile Karamat for doing so in crude terms that question his manhood. Sharif appointed General Pervez Musharraf, believing that a Muhajir army chief would have less institutional support and thus would pose less of a threat.

Sharif profoundly irked the army with his significant peace overtures to India, which were reciprocated by India’s Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Even as the two men were engaging in the famed “bus diplomacy”, the army was planning the Kargil operation to tank any prospects for peace. Sharif claimed that he was not knowledgeable about the army’s preparations for Kargil and was ill-prepared for the international opprobrium that would befall him when the Pakistan army’s ingress into Indian territory became public. Both China and the US told him unequivocally to withdraw the Northern Light Infantry troops, deceptively described as mujahideen, to Pakistan’s side of the Line of Control (LoC). After the dust had settled, in October 1999, Sharif attempted to oust Musharraf while he and his wife were on a plane returning to Pakistan from Colombo. Sharif’s government refused to let his plane land, which was tantamount to a death sentence for Musharraf and the other passengers. The army moved in swiftly. Musharraf ruled Pakistan until 2007.

ZARDARI QUEERS THE ARMY’S PITCH

Oddly, neither Sharif nor Bhutto ever made serious attempts while in power to reverse Zia’s changes to the constitution, including the Eighth Amendment, even though it was perhaps the most important tool that the army had to prorogue parliament. Then, in 2010, then-president Zardari and his party did the unthinkable. They passed the Eighteenth Amendment, which Zardari signed into law. The amendment, which was a dramatic reversal of past efforts to concentrate power in the centre, stripped the president of key discretionary powers, including the right to prorogue parliament. Zardari said of the measure, “The doors have been shut for dictatorships.”

Without this major lever, the army had to innovate other ways of pressuring prime ministers who had the folly to believe that they were in fact the head of government. And innovate it did. It increasingly relied upon influencing the courts, selective use of anti-corruption instruments, street politics and the evergreen option of signalling its discontent to motivate counter-coalitions to act against the prime minister. This is in addition to the army’s well-honed skill at rigging elections before, during and after election day.

Imran Khan, like Nawaz Sharif himself, is a political creature of the army. With Nawaz Sharif seeking to prosecute Musharraf for treason and with no palatable leader available in PPP, the army was bereft of options after Sharif was ousted from the prime ministership in 2017 after the country’s Supreme Court unanimously indicted him on corruption charges unleashed by the 2016 Panama Papers leak. Imran Khan was the army’s only choice. It was likely a bitter pill to swallow as Khan had been publicly critical of the army and its policies prior to making a Faustian bargain with the institution. Despite strong appeal among young voters, Imran Khan’s previous performance at the polls was lacklustre. To enthrone Khan, the army began engineering the victory long before election day. The army enabled Khan to form the government by stitching together a “coalition of the billing”. The price for the army’s services in hoisting Khan to power was an ever-increasing role in the governance of the state which became known as a “hybrid regime”.

KHAN’S DOWNFALL

Like prime ministers before him, Khan made the mistake of believing his own rhetoric and apparently believed that he was too important to be ousted. No doubt he thought—and clearly still thinks—that his street power would be decisive. Khan did not seem to appreciate that his governance failings reflected poorly on the army because it was the army that emplaced him and it was widely understood that Khan was the army’s man. Consequently, Khan’s general standing with Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) Qamar Javed Bajwa began to buckle in 2021 largely because of Khan’s shambolic governance, rampant inflation and unemployment; corruption allegations undermined the army’s own standing.

Khan also broke the terms of agreement set by the army when Benazir Bhutto first became prime minister: he had different foreign policy preferences than the army. Whereas the army wanted some kind of rapprochement with the US while dampening tensions with India, Khan made virulent hostility to the US and India a prominent feature of his populist platform. No doubt, this is part of Khan’s curb appeal. The US has never been very popular in Pakistan; however, the so-called Global War on Terrorism exacerbated traditional antipathy. Similarly, Khan exploited Pakistani anger at Indian moves to strip Kashmir of its previous status when it dispensed with Articles 370 and 35A. Khan and Bajwa also disagreed on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Since 2007, Russia and Pakistan have slowly and steadily deepened their relationship, inclusive of security ties. While Khan was in Russia to meet Vladimir Putin on the day of the invasion, Bajwa publicly condemned the outrage.

This ruckus is a public fiasco that underscores the army’s longstanding argument that Pakistan’s civilian rulers are corrupt, self-serving louts. The longer this street politics goes on, the better the army looks. This does not mean that the army is hungry for a coup. Far from it. After all, what consortium of lunatic generals would want to have direct responsibility for the current governance cock-up?

The final blow was Khan’s interference in the army’s internal affairs. When Bajwa sought to replace General Faiz Hameed as the head of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Khan thwarted this move. Hameed was responsible for engineering Khan’s 2018 electoral victory. Khan likely wanted him to remain ISI chief to ensure his re-election in 2023.

This very visible rupture between Khan and the military signalled to the opposition that it was possible to unseat Khan. This was further enabled by his coalition partners defecting from the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). With a no-confidence vote tabled, Khan’s ouster seemed straightforward. However, Khan surprised everyone when he made a Trumpian move of claiming that this move to remove him was in fact a foreign-sponsored plot. He claimed that he was threatened by the US and that the US was behind the move to unseat him. He declared the opposition to be traitors and tools of the US and then he invoked national security measures in the constitution to prorogue parliament and called for fresh elections. Khan’s version of The Great Steal was widely popular among his supporters who embrace his anti-Americanism. The matter of the constitutionality of the move went before Pakistan’s Supreme Court which declared Khan’s move to be unconstitutional and restored parliament. Upon reconvening, it held the no-confidence vote which sent Khan packing from the official residence. The opposition appointed Shehbaz Sharif of PML-N as prime minister.

WHO WON WHAT?

While many are wont to praise this sequence of events as a victory for democracy, I am more sceptical of this enthusiasm for several reasons. First and foremost, Khan’s Great Steal has mobilised his supporters who have assembled in massive protests. The crowds are disporting with signs identifying Bajwa as a traitor. No doubt, the army as an institution is discomfited by this move. Indeed, it was the increasing public hostility to Musharraf that forced him to step down as army chief in 2007. Bajwa himself has been controversial within the institution because of his extensions and accusations of corruption. The army may find it expedient to have a new chief.

Second, this coalition is a dog’s breakfast of partners who have nothing in common other than their desire to replace Khan. Shehbaz Sharif inherits a derelict economy with ever-growing inflation and unemployment. With Russia’s war in Ukraine likely to go on for years, price pressure on oil and gas is likely to increase. The new government will likely have to reverse Khan’s populist subsidies on these commodities which will not be popular. Under the best of circumstances, righting this economic ship would have been hard. Khan’s “youthia brigades” and their massive public shenanigans will make this even harder.

Imran Khan’s Great Steal has mobilised his supporters who have assembled in massive protests. The crowds are disporting with signs identifying Bajwa as a traitor. No doubt, the army as an institution is discomfited by this move. Indeed, it was the increasing public hostility to Musharraf that forced him to step down as army chief in 2007. Bajwa himself has been controversial. The army may find it expedient to have a new chief

This ruckus is not a signifier of a vibrant democracy; rather, it is a public fiasco that underscores the army’s longstanding argument that Pakistan’s civilian rulers are corrupt, self-serving louts who enrich themselves at the public’s expense. The longer this street politics goes on, the better the army looks. This does not mean that the army is hungry for a coup. Far from it. After all, what consortium of lunatic generals would want to have direct responsibility for the current governance cock-up?

The real question is what happens next in the 2023 elections. While Nawaz Sharif proved to be a thorn in the army’s side, Shehbaz Sharif has had a more amicable relationship with the faujis. He may well be the best option for the army in 2023. However, the global economic situation is not propitious due to Covid-related production shortages in China and fuel prices due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Moreover, with the Taliban at large and in-charge in Afghanistan, the Pakistani Taliban have also experienced a terrorist renaissance. The Islamic State is competing with the Pakistani Taliban for the title of most savagely murderous. With Pakistan’s political house in such disarray and given other domestic and foreign policy priorities, the US is unlikely to seek a reset with Pakistan with any alacrity. For all of these reasons—among others—it is highly unlikely that in 2023 the public will be enthusiastic about Sharif. I anticipate that sooner rather than later this coalition will begin to fray with PPP asserting its own equities and mounting a resistance to PML-N in 2023. On whose side will the army tip the scale?

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba