The Wounded Happiness of Salman Rushdie

IT WAS A SUNNY MORNING IN UPSTATE New York on August 12, 2022, and Salman Rushdie was on stage at the amphitheatre in the Chautauqua Institution to give a talk on writers’ safety. Then he saw, in the corner of his right eye, the man in black leaping out of the audience, rushing at him like a ‘squat missile’. Rushdie came to his feet, faced him, raised his left hand in self-defence. They had twenty-seven seconds together. The author received more than a dozen knife wounds, though he never saw the knife.

The knife severed all the tendons and most of the nerves of his left hand, inflicted two deep cuts in his neck, and more on his face, chest and thigh. The deepest wound was in the right eye; the knife went all the way down to the optic nerve, stopping just before touching the brain. His vision was gone. “He was just stabbing wildly, stabbing and slashing, the knife flailing at me as if it had a life of its own, and I was falling backward, away from him, as he attacked; my left shoulder hit the ground hard as I fell.” He survived, and he was lucky, as a doctor would tell him later, because the attacker didn’t know how to kill someone with a knife.

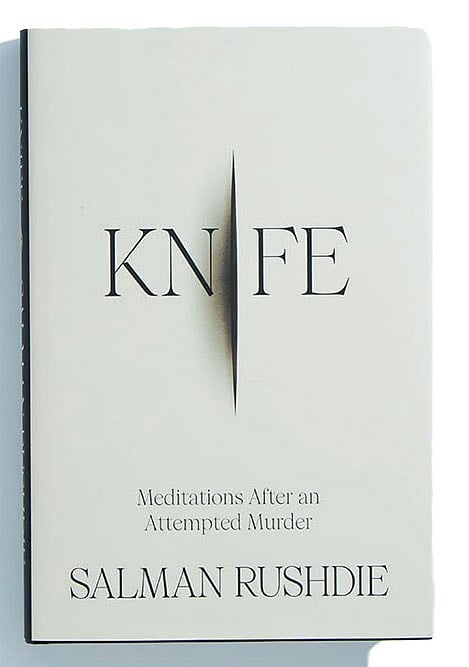

Live. Live. That was Rushdie’s mantra through the ordeal after the attack. Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, his second memoir (the first was Joseph Anton, the title a homage to two of his favourite writers, Conrad and Chekhov, and, with its novelised style, dealing more with his Fatwa days), is a survivor’s testament to being alive to tell the story that matters most: the life that he has almost lost. It is a writer’s reclamation, assertion and rejoinder. The knife that failed to kill one of the world’s most celebrated—and equally misread—storytellers is not what lingers after the last page of this memoir, but the knife of language that cuts through the false certainties inserted between life and death.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The attacker, whom Rushdie calls “the A”, a more decorous version of the Ass, caught up with him thirty-three years after Ayatollah Khomeini’s Fatwa against the author of The Satanic Verses. When he saw that “murderous shape” coming for him, his first thought was: So it’s you. Here you are. He, as a collective noun of hate, was always there, lurking in the receding shadow of a revolution desperate for apostates and blasphemers. For ten years after Valentine’s Day in 1989, annus mirabilis elsewhere in the world, Rushdie lived in hiding, as if he was entrapped in a metaphor taken from his own imagination. It was an unequal clash between the Word, brought to the world by Imams, like the one in The Satanic Verses, raging against history, and the words, as written by writers like Rushdie for whom nothing was sacred.

The A dragged him back to that narrative dead zone, to a place and time he had no intention of revisiting. Knife, even as it tells in evocative prose the painful act of overcoming death, of the transition from a life held together by metal staples and fentanyl to a second chance, of a miraculous recovery by someone who never believed in miracles, is about life and love, about writing aside an experience that stood in the way of stories Rushdie wanted to tell.

Were there intimations, and visions of foreshadowing? On the night before the lecture at Chautauqua, standing alone outside the guesthouse and watching the full moon shining down on the lake, he thought of, in his customary free-associating way, books and films. Georges Méliès’ classic silent film of 1902 about moon landing, Le Voyage dans la Lune, in which a spaceship wounds the moon’s right eye, came to his mind. Next morning he would lose his own. And two nights before the event, he had a dream about being attacked by a gladiator-like figure wielding a spear in a Roman amphitheatre. He almost cancelled the Chautauqua event.

The kindness of strangers and the triumph of medical science would make premonitions and free associations redundant. What the knife that the A held wounded was not his vital organs alone. It wounded something equally precious: happiness. Rushdie was deep in it when he was all set for talking about keeping writers safe from harm that morning, with the cheque for the speaking fee in the pocket of his Ralph Lauren suit. This book, even as it portrays the writer’s Wolverine-like capacity to suffer and recover, is a love story too.

In the love story, a four-time divorced writer in his seventies meets a much younger African-American poet named Rachel Eliza Griffiths at a PEN event in New York. The fate-shifting moment came when the smitten writer followed her through a sliding door and hit the glass. He didn’t pass out, but there was blood all over his face. When he took a cab and went home, Eliza was beside him. At home, she would tell him that they could be good friends now. “I’ve got enough friends. This is something else,” he told her. He fell in love, literally. “One of the most important ways in which I have understood what happened to me, and the nature of the story I’m here to tell,” he writes, “is that it’s a story in which hatred—the knife as a metaphor of hate—is answered. And finally overcome, by love. Perhaps the sliding door is an analogy of the coup de foudre, the thunderbolt. A metaphor of love.”

The Eliza that appears in this memoir is an invocation of love and happiness, a subject he was keen to write as a story. It never happened. The five years they have been together, the last one year as husband and wife, for him was the happiest story of his life, and he could relive it only with awe and adoration. It was a time when happiness was private and intimate; they even endured Covid together during the first wave of the pandemic. It was this delicately built universe of two lovers that the knife of hate cut apart.

RUSHDIE REASSEMBLES HIS shattered world with the easy elegance of a memoirist who finds the echoes of his life in the pages of others—and even in his own. The knife itself has its back story written in one of his novels, Shalimar the Clown, set in Kashmir. The novel was born from the image of a bloody act: the assassin with a bloodied knife standing over his victim. And in The Satanic Verses, many passages, including those about the Imam and the scribe who puts his words against the Word, would leap out of the pages to match their creator’s life. As he was recovering from the attack, the opening line of the novel returned to him with a reminder: “To be born again,” sang Gibreel Farishta tumbling from the heavens, “first you have to die.”

On his journey back to his second life, the visions he had were made of alphabets, as if, even as he experienced near-death, it was the magic of language that clarified the new reality. In his visions rose new domes and halls, the Sheesh Mahals and the Hagia Sophias, the Fatehpur Sikris and Red Forts. In the loneliness of the writer who just experienced what death looked like, language played comforting games, the only alternative he could afford then.

Or, it was a time when he could take comfort in the company of writers like Naguib Mahfouz and Samuel Beckett, both suffered knife attacks. Mahfouz was a victim of cultural terrorism, for his novels “offended” Islam. Beckett was on his way home in Paris, in 1938, when he was attacked by a pimp. The knife narrowly missed his heart and lungs. At the trial, Beckett asked him why, and the reply was: “I don’t know, sir. I’m sorry.” Still, the newest entrant to the club of wounded giants could not have expected such an enigmatic answer from his attacker.

The A was steeped in his closed world of hate. He didn’t like Rushdie, though he had read only a couple of pages of his work; but he had seen the writer lecturing on YouTube. He wanted to murder Rushdie because he found him “disingenuous”. He of course admired Ayatollah Khomeini, and his opinion of the writer. He was the Great Islamic Revolution’s faraway child, biding his time in a cheerless basement. The so-called lone wolf has never been all that lone; he lived with the images of the enemy, conjured up to terrifying perfection by the Book-keepers. In the evolutionary story of the so-called sword of Islam, apprentice revolutionaries like the A are the new enforcers of the order.

Rushdie has an imaginary conversation with him. The author tells him, “I’m trying to understand you. You were only twenty-four years old. Your whole life ahead of you. Why were you so ready to ruin it? Your life. Not mine. Yours.”

“Don’t try to understand me. You aren’t capable of understanding me.”

“But I have to try, because for twenty-seven seconds we were profoundly intimate. You put on the mantle of Death itself, and I was Life. This is a profound conjoining.”

“I was ready to do it because I was serving God.”

“You’re sure of that. This is something your God wanted to do.”

“Imam Youtubi was very clear. Those who are against God have no right to live. We have the right to end them.”

“But most people on Earth do not follow your God. If they are for other gods, or no god, do you have the right to end them too? Two billion people following your God. Six billion others. What do you think about them?”

“It depends.”

He is a familiar character in the larger war for scriptural purity, the basement rat as holy warrior, fattened by the sewage system of social media. The indoctrination of the new radical of Islam came from the weaponised technology of groupthink. The man with a murderous urge wielding the knife, whether it was somewhere in the sandy Levant that resembled the Jahilia of The Satanic Verses or on a civilised stage in upstate New York, was inevitable. Rushdie quotes John Locke to know the interior life of the A: “I have always thought the actions of men the best interpreters of their thoughts.”

The Rushdie oeuvre is eventful, maybe as eventful as it can be in an India-inspired imagination. So is his life after the Fatwa. His life was written into the larger histories of unfreedom and unreason, as a cautionary tale and as a daring rebuttal. Was his writer’s life altered by the knife wielded by the A? Will there be a reconciliation between the multiple Rushdies, constantly invented and modified by all kinds of readers, some holding knives, and Salman? He is optimistic, for such a reconciliation alone ensures a free passage of fiction, his lifeline.

Salman Rushdie wrote Knife with partial vision. What we read in it is life writing back to a lie with incandescent elan.