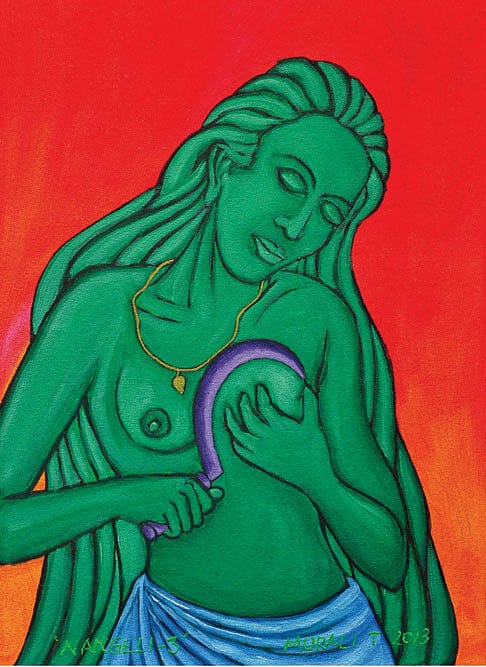

The Legend of Nangeli

It is said she was bold, beautiful and devout. It is said she asked questions. It is said she wouldn't cow down before either the feudal, casteist hierarchy or the lewd male gaze of the upper class.

Her name was Nangeli.

She is no heroine of the written history. Some say she is just a legend of the times. Some say she is part of folklore. Some say, 'Show us the proof.'

Nangeli is not to be found in the pages of history of Kerala, nor of Travancore, the erstwhile princely state. Nor is she included in the curriculum to educate and inspire the younger generation to learn about what she did to stand up against an inhuman system—be it caste or the lecherous leer of the upper caste.

But why does the name of Nangeli still prevail when we make strides in women's development in the 21st century? Why is she still a point of reference for women's liberation struggles and the fight against casteism or other systems of discrimination?

In the early 19th century, Nangeli cut off her breasts in protest against a horrific tax called the 'breast tax', and presented the bleeding organs on a plantain leaf to the king's official who had come to collect tax for covering her breasts.

She died bleeding. Her husband, Chirukandan, killed himself by jumping into her pyre. It was early 19th century Travancore. Most women never even thought about rebelling against the system.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

From the Ezhava community, Nangeli is believed to have lived in today's Cherthala in the district of Alappuzha. In Travancore, which had levied some strange taxes on its lower-caste people, breast tax was slapped on lower-caste women if they wanted to cover their breasts.

"The incident happened in 1803. It created a lot of anger and the practice of collecting breast tax was put to an end," says Sugathan, who has mentioned Nangeli's story in his book Oru Desathinte Katha, Kayarinteyum.

Nangeli cutting off her breasts was a trigger for women's struggles for liberation in the region. Nadar women, who revolted against the atrocities of caste, converted to Christianity. Two of them who had covered their breasts were stripped and hung in public.

Would Nangeli have paid the tax if she and her husband had the means? Historians like Manu S Pillai believe that Nangeli's act of cutting off her breasts was not just a protest against the upper-caste gaze but a revolt against the caste system itself.

"The Nangeli story, as it is related popularly today, is somewhat misunderstood. There was a poll-tax chargeable on avarnas by the state or the feudal lord, depending on where in Kerala we are speaking of, and this, for men, was called talakkaram, and for women, mulakkaram. Sometimes, it was simply called talappanam for everyone. But beyond nomenclature, it had no connection to the breasts, or to covering the breasts," says Pillai.

"She was not fighting for the right to cover herself, 'protect her modesty', or anything like that. She was resisting an oppressive, caste-based tax. The battle is about caste, not about virtue or the 'right' to cover up. That was not a 'right' in local eyes at all till the late 19th and early 20th centuries," he adds.

In Nangeli's day, no woman thought her virtue depended on whether or not she covered her breasts. The savarnas had a loose shawl, which even they took off in the presence of their superiors: Nairs before Namboodiris, Namboodiris before the deity in the temple. In fact, ordinary Brahmins had to take off their upper cloth before the king as well.

There are some who argue that Nangeli is a fabrication because no 'records' exist of her. Malayinkeezhu Gopalakrishnan, a Travancore historian, says that he couldn't find any mention of, forget Nangeli, even 'breast tax' in Mathilakam Records. The Mathilakam Records, which were kept inside the Sri Padmanabhaswamy Temple, kept a record of administrative details of Travancore. "But just because I couldn't find it anywhere in the Records, I am not saying Nangeli's incident didn't take place," explains Gopalakrishnan.

However, Manu S Pillai refutes the argument. "Written records are usually left by upper-caste, literate elites. Avarnas and others recorded their tales and stories in song, lore, and collective memory. Nangeli is one such source from oral history. As such, it is not surprising: Dilip Menon [academic and scholar], for instance, has shown how in Malabar, often individuals who were wronged or died because of unjust causes were soon memorialised in groves and little shrines. Their stories were passed down orally. So, too, in Travancore, Martanda Varma's cousin who is forced to kill herself after he murders her brothers 'becomes' a Yakshi—it was the local people who enshrined her that way. There is much in oral history that is of value. The story of Nangeli is communicating resistance. Just because it is not written down on a palm leaf manuscript does not dilute its significance."

Women in Kerala across the board, like men, did not cover themselves—it was only in the 1920s that the first Namboodiri Brahmin women wore blouses (and they were promptly ostracised by the orthodox). There was, however, a loose shawl that was the privilege of savarnas, men and women both. But it was not really intended for covering the breasts as much as a mark of honour.

"That is why when in the 19th century the Nadar-Nair conflicts took place, the issue was not about Nadar women covering their breasts. They were permitted to wear kuppayams or blouses and nobody objected to that. The issue arose when they wore the loose shawl, because the latter was a caste privilege, and the prerogative of the Nairs as their superiors," adds Manu S Pillai.

Visual evidence as well as portraits of women—Namboodiri women included—even into the 20th century shows them topless, including the queens of Cochin. "It was the Victorian gaze that brought in the idea that the female body ought to be covered up, as a result of which the blouse and the upper-cloth assumed a new significance as a mark of modesty. The loose shawl that was a caste privilege for men and women both now assumed an added significance when referring to women, as essential to their virtue, decency, etcetera."

On many indices, Kerala tops the table. It is true in the case of women's development. Women have played their part in the evolution and development of Kerala society—from the days of Travancore till now, especially when we compare them with women from other societies in the country.

Robin Jeffrey, social historian and scholar on Kerala society, says: "I think it has been one step forward and two steps backward for many women. Many of today's Malayali women are expected to be earners as well as household managers—and, at the same time, to be subservient to men, both at home and in public life."

Jeffrey's words echo the hypocrisy of the general attitude towards women in Kerala. Educated and progressive, the women in Kerala are expected to be at the forefront of society but the fact remains that women are still 'supposed' to play second fiddle to men in leadership.

Even with its tall claims of women's development, Kerala is yet to have a woman chief minister. "I think it was a mistake and an injustice when Gowri Amma did not become Chief Minister in 1987. She was an outstandingly experienced administrator and politician. But patriarchy in Kerala is so strong in all classes and communities," adds Jeffrey.

"The kudumbashrees and the presence of women on local government bodies produce plenty of talented women, but the obstacles to political careers are big and not just in Kerala. When Julia Gillard was Prime Minister of Australia, senior male opponents were happy to address meetings under banners saying, 'Ditch the witch'—and the whispering campaigns were far worse."

Even though representation of women is made on paper, it remains a tokenism when it comes to reality. Scholars and experts on women's issues believe that we will not see a woman chief minister in Kerala in the near future. Academic Swapna Gopinath says: "I don't think it will happen anytime soon. As a society, we have regressed in terms of gender equity since saffronisation. Just look at the ratio of women's participation in jobs or public spheres."

Meena T Pillai, Professor, Institute of English, and Director of Cultural Studies, University of Kerala, says: "It will still take some time because, of late, the crisis in Malayali masculinity shows no signs of being resolved. This has paved the way for a popular culture that remains tied to gender stereotypes and a paranoid fear of empowered women. Condescension under benevolent patriarchies has its limits."

"Everything is relational. Women have achieved social development indices in Kerala that are enviable. But at the same time misogyny is rampant. Many women are more sabotaged in the intimate and private spheres of life," she adds.

Gopinath shares that point of view: "Women in Kerala constantly fight a battle for their rights within the domestic spaces. Even as the woman reaches great heights with her education and work, the battles have to be fought fiercely."

Manu S Pillai says that, apart from the well-known names of women who have excelled in their given field over the years, there are many 'nameless' women who have contributed significantly to Kerala society.

"Besides the poets and queens (Manorama Tampuratti or Sethu Lakshmi Bayi), doctors (Mary Poonen Lukose) and legal luminaries (Anna Chandy), there are countless women who have remained nameless. The agrarian economy of feudal Kerala depended to a great extent on the labour of avarna women: this is a material contribution they have made. Every temple built, every historical monument erected, every physical reminder of the past came from revenues that were derived from a working class in which women and men were equal partners. Lower-caste women especially made immense contributions to this, even in the advancement of their communities in the period of the Kerala Renaissance," he says.

Jeffrey's Decline of Nair Dominance shows, for example, how women were integral to the rise of the Ezhava community, and they also contributed through the pidiyari scheme to the Vaikom Satyagraha, though they were far from the actual site of the protest. "Songs that used to be sung by workers in the fields—these had a strong gender component since women were also among these workers. Though it is easier to find the stories of elite women in positions of influence, we must not forget those who worked on the ground and, physically, helped build what Kerala society is today," adds Manu S Pillai.

Many questions are raised these days about gender and power. Manu S Pillai says though matriliny has its own pros and cons, it has given the women in Kerala "a deal fairer in many respects" than what was available to them elsewhere in India.

"Matrilineal society was not an equal society between men and women—it was only less unequal than patriarchal systems elsewhere. Even so, it certainly created avenues of power for women, and in matrilineal families, the women of the house could often exercise tremendous influence, including in management of the lands and other economic areas. There is often a misconception that in matrilineal families, it was the male Karnavan who was the 'real' power: this, as some research has shown, was actually a consequence of colonial recognition of the male as the 'head'.

In the days before power was gendered, if a woman was the eldest in the family, she was the highest authority of the family. "Missionaries had often commented on this," points out Manu S Pillai. "Augusta Blandford, for instance, wrote how the eldest woman in a Nair family commanded much regard and how even her sons would not sit in her presence, with the lady enjoying complete obedience; in the Zamorin's family, while there were no ruling queens, the Zamorin always referred to the eldest woman, even if she were younger than him, as 'mother'; in the Arakkal Muslim family, women had a direct claim to the throne over and above their brothers, if they were born first."

But once power became gendered through influences, women, gradually, began or expected to play second fiddle to the man or men in the family, and as an extension in society and in other 'spaces'.

"Gender policies [in Kerala], especially with regard to transgender rights, are all set brilliantly on paper. That is definitely a first step, no belittling that. But it is in social attitudes and the cultural unconscious that paradigm shifts have to be effected," says Meena T Pillai.

"It's all tokenism," adds Gopinath. "Look at the women's studies centres in our universities. They do nothing to empower young girls."

Contemporary Kerala society and media are rife with incidents of 'objectifying' or 'problematising' women's calls for liberation or social equity. Be it the Sabarimala issue regarding women's entry to the temple or the women's collective in cinema, they are often watched through a lens of prejudice or conditioned male psyche.

However, women writers have always written powerful stories about women, and their concerns for the gender. "There are brilliant writings by women from Kerala that crack open the bunds of its conservative, regressive, social fabric. I have utmost faith in the powerful language of subversion that Malayali women writers and poets have historically unleashed on the literary public in Kerala," says Meena T Pillai.

Dwelling on the life and works of K Saraswathy Amma (1919-1975), J Devika, historian, feminist and academic, writes: 'The younger generation of women-writers in Malayalam whose anti-patriarchal writing is now a powerful voice in Kerala's literary public, are clearly her literary granddaughters. Consider, for instance, the writings of K.R. Meera, who depicts a world of patriarchy in utterly de-romanticised terms and whose narration is marked by black humour. Or, Sara Joseph's wickedly sarcastic tales of marriage and its follies, such as in 'The Scooter'. The present generation laughs at patriarchy like never before.'

Power balances and gender equation changes are temporal and connected to the socio-political context. Even though Jeffrey says that women in Kerala are much better off than in many other societies, he is quick to add that Kerala is no Finland, where the prime minister and the leaders of the four parties making up the coalition government are all young women.

Apart from fighting the prevalent caste system and discrimination, Nangeli combines two protests in one act. By cutting off her breasts, she removes the 'sex organs' to protest the lecherous gaze of upper-caste men (or, in today's context, any brazen male gaze). By removing her breasts, Nangeli also equates women to men—or a social equality.

But the question lingers: Is it about equality or uniqueness?

By cutting off her breasts, Nangeli proves that it is not about man and woman being equal or not, but about being unique in their respective roles.