Between Independence and Freedom

An unsuspected, and hence uncorrected, fallacy has caused much confusion in political philology, impairing analysis and understanding of the modern nation state.

Independence is not synonymous with freedom.

Both are essential to the contemporary ideal. They are compatible and often complementary. But the two virtues follow different trajectories and attain separate objectives. Independence is liberation from foreign or colonial rule; freedom is a right of every individual citizen which may be denied as easily by an indigenous ruling elite as by any foreign power.

India and America celebrate their independence on August 15th and July 4th respectively to commemorate the triumphant moment when they threw the British out of their lives. England has no such day since the English claim that they have never been ruled by a foreign power. Perhaps that was so long ago that amnesia is forgivable. The Romans invaded England in 43 AD and left only in 410 AD, when troops were summoned back to Italy, then being ravaged by 'barbarians'.

The only memorable, and near-successful, British challenge to Roman might occurred early. In 60 and 61 AD, the queen of the Celtic Iceni, Boadicea, known in her native Welsh as Buddug, defeated Roman armies in battle and burnt down the coloniser's capital, Londinium, forcing Nero, the emperor, to consider retreat. But his general, Suetonius, regrouped and won the war. Buddug, only 31, poisoned herself. Her pragmatic husband, Prasutagus, ruled as an ally of the Romans and left his kingdom to the Romans in his will. Colonial behaviour has some interesting antecedents.

However, the British do retain a soft spot for Boadicea. She is not honoured on the holiday calendar, but her memory is preserved in a heroic statue at London's Westminster Bridge and in a romantic luxury perfume misnamed Boadicea the Victorious.

Modi Rearms the Party: 2029 On His Mind

23 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 55

Trump controls the future | An unequal fight against pollution

The Norman conquest of Britain in 1066 was more nuanced, for the triumphant Frenchmen from Normandy soon blurred the difference between dependence and independence. The new conquerors did not rule England from France; they ruled swathes of their native land from England. Normans became the new English establishment. In a delicious paradox, French history books now venerate St Joan of Arc for liberating France from Norman royalty.

There is no confusion, however, in England's history of freedom. It is legitimately traced back to the Magna Carta Libertatum, signed by a reluctant King John in 1215 to obtain support of the landed nobility against a French invasion. The charter gave barons the right of consultation on raising taxes through a council; this evolved into a foundational institution of freedom, Parliament.

From the late 18th century, Britain and France began to devote more energy on conquering Africa and Asia than destroying each other, creating two formidable empires. Britain became the dominant power because India glistened as the jewel in its crown.

India won independence on August 15th, 1947. When did Indians become free?

A purist might argue that freedom came with the adoption of the Constitution in 1950 with its golden triangle of fundamental rights to life, faith and free expression. But the generation of Mahatma Gandhi's disciples made a persuasive case for an earlier date: between 1920 and 1921, during the non-cooperation movement, when Gandhi mobilised the masses to destabilise the mightiest empire in history with the moral power of one of the greatest ideas in history, non-violence.

Gandhi could not win independence in 1921, but he freed the Indian mind from subservience.

Three hundred million Indians from Khyber to Burma were not shackled by a hundred thousand soldiers and bureaucrats. They were imprisoned by fear. As Gandhi understood from an early age, British rule depended not on British strength but on Indian weakness. Fear of the British kept the British in power. Once fear was gone, the British would follow. That was the essence of the Mahatma mantra.

Tensions between authority and freedom do not disappear with independence. The tussle between individual freedom and authority is a continuing narrative. At what point of inflexion can freedom become the convector of anarchy?

In democracies, governments have to address such questions on a regular basis. In dictatorships, they know the answers before any questions have been asked.

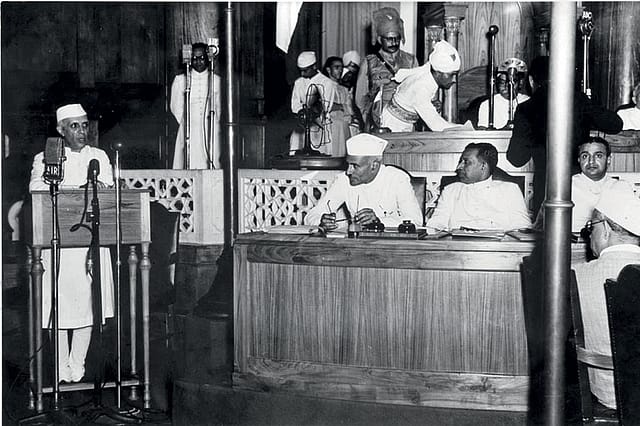

Democratic India emerged from colonisation with both independence and freedom intact. Its first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, had to answer this crucial question immediately after the adoption of the Indian Constitution in 1950. On May 10th, 1951, he moved the first amendment to the Constitution seeking changes to fundamental rights. He wanted to validate the abolition of huge land holdings under the colonial zamindari system and ensure special consideration for weaker sections, but he was also very certain that limitations were required in Article 19, which guaranteed freedom of speech and expression. The First Amendment prevented abuse of this freedom.

Freedom has survived this qualification in India, as indeed it has elsewhere. There is a mid-point trade-off that can be easily determined by the wisest asset in a democracy: the common sense of common people. Citizens recognise a tipping point when they see it. A law against libel, provided by Nehru in India, does not throttle freedom. It protects freedom from misuse and abuse.

Some self-proclaimed rational systems consciously eliminate any opposition in pursuit of what they assert is the higher good. Communism is one such ideology. Communists are convinced, with all the passion of believers, that the rightly guided party must be obeyed, feared and venerated with the zeal of a religious conviction. The Party is God in an atheist doctrine. When this deity seeks a sacrifice, it must be offered along with thanksgiving prayer, for the omnipotent Party can do no wrong. There can be no accountability for any policy disaster, even when mistakes lead to famines that kill countless millions, for the Party's benign intentions absolve it of all sin. Truth becomes flexible. History is written only to be rewritten. From one perspective, such rational deism is not totally distant from the ethos of theocracy.

No guardian of the faith can make a mistake in a theocracy either, since service to God sanitises him from infection. A theocracy can protect national independence with commendable commitment, even as it limits the people's freedom with similar fervour. The high priests of both atheism and theism also know that a mendicant's garb is a useful disguise when they pronounce, in stentorian tones, that the intellectual incarceration of citizens is necessary for the good of the state and the well-being of the people.

High priests are careful enough to keep their own backs protected by an obedient army; but sometimes an army runs the priesthood, particularly if it is incoherent or rife with schism. The uniformed self-appointed wardens of nationalism then argue with thin logic that the nation would disintegrate without their firm hand. In real terms, this is a confession that the nation cannot be held together except by force.

Pakistan is a good instance of an army perched on a pedestal above the law, closer to God than the hoi polloi at the base and politicians hovering in-between. The only unqualified freedom is the freedom to exalt the armed forces in every instance. Criticism becomes heresy, punishable by inquisition.

The difference between independence and freedom is not semantic. The individual's quest for freedom, with its many variables, is as old as the imposition of hierarchies in social structure. Independence has had a more recent, more patchy journey, becoming a dominant reality only in the 20th century. The 21st is the first century in human experience which can be described as a true age of independence.

Empires began to erode in the 19th century, but monoliths have a long shelf life after the due expiry date. World War I dealt a hammer blow to the Tsarist, Austrian, Ottoman and German empires, but did not affect the credibility of the concept as a workable proposition. Britain and France, assuming infallibility after victory in 1918, stretched their realm to taut limits. Smaller European powers from the winning side continued as before. In Moscow, the Soviet Union reinvented the Tsarist empire as a multilateral Marxist cooperative.

Till the adoption of the United Nations Charter signed by 50 countries on June 26th, 1945 in San Francisco, which offered equal rights to 'nations large and small', conquest was legal. You could, and many did, question the morality of the British Empire, but no one questioned its legality. Governments were not always in the forefront of invasion; merchants could hire mercenaries and raise their flag upon any domain, as they did so successfully in India.

Till World War II, the world was a violent giant seesaw. Japan could sweep through Asia, and be swept back.

Germany could stomp through Europe from Paris to Moscow, and be driven back to a shattered Berlin. If Japan and Germany had not been defeated, they would have made their possessions into colonies.

The United Nations has not ended war; far from that. But no warrior power now attempts to force the subjugation of another country, the occasional exception apart. The fashionable justification for war is now regime change, and it is becoming less fashionable by the year. In too many cases, regime change, when achieved, has come with an attached bill that has become a drain on the resources of the victor.

World War I ended in 1918 on a palate of grey areas; the second war ended with far clearer demarcation between victor and vanquished. But both had lessons to learn. The defeated understood that aggression brought corporal punishment. More remarkably, victors also realised that empires were now untenable.

Independent countries would become building blocks of the architecture of strategic stability.

With India's independence, the end of colonisation became a matter of time.

European empires consolidated over three centuries crumbled in three decades.

But Europe itself, having suffered a hundred million dead in the 31 years between 1914 and 1945, experimented with a new dimension in its search for sustainable peace within.

The European Union (EU) is a mix of idealism and fear converted into geography. The fear was not of the other. Western Europe was afraid of its rearview mirror; worried that it would become what it had left behind if it was not tethered to a different horizon.

And so, European nations willingly ceded a part of their strategic independence to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and a part of their economic independence to a proportional-ratio bureaucracy in Brussels. They achieved this without any compromise with the freedom of their citizens. The elixir proved so powerful that Britain, always careful of its distinctive identity, was drawn in. The decade of exhilaration came in the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when members of the Soviet-controlled Warsaw Pact clamoured to join the EU as a guarantor of safety, growth and freedom.

Irony is often just a few steps behind success. Security survived the pressures of unforeseen events, like the Balkans conflict or the more recent immigration crisis; and economic cooperation managed to contain, if not subdue, the difficult fires of regional disparity.

Tensions generated by freedom were more intractable. The drumbeat of media criticism, the peals of pub laughter at the occasional ludicrous Brussels regulation and the easy incitement to national pride or pretension became staples of public discourse.

Eventually, Britain's exit was not due to the price of fish, but born of a belief that the country could do better without Brussels. A perceived loss of independence persuaded enough Britons to leave the EU. This is why champions of the EU pick up their handkerchiefs when they hear the word 'nationalism'.

The dilemma is, however, more serious than Britain's departure. How do you disentangle the people from nationalism in an era of the nation state? In Britain, this was not the nationalism of Colonel Blimp or the bulldog scowl. In the days of empire, Britain justified supremacism with the propaganda that it brought unmitigated progress to ignorant if not barbaric natives. The empire was international. Vast spaces subsuming ethnicity and language could be painted in a single political colour, and governed from a single capital. What else could explain such British success except inherent supremacy? Pride was the privilege of the conqueror; the defeated had to place their interests at the feet of the Big Emperor or Empress for their own benefit.

Today's Britain is fashioned by pride in itself, not the puff of its acquisitions. There are similar populations across the EU, ready to test their fortunes without a crutch.

Britain is also a union, with a flag called the Union Jack, an emblem of collaboration between the three patron saints of England, Scotland and (Northern) Ireland—George, Andrew and Patrick.

History never ends, does it? The rhetoric that restored the waters of the English Channel into a hard border is now raising and cementing that old Roman wall between England and Scotland built by the conquerors of England 2,000 years ago. The English want to be British rather than European. It would be yet another twist in a tale full of unintended consequences if they ended up neither European nor British, just English.