Viral Sexuality

Like any other businessman whose product depends on the smooth functioning of vast global supply chains, when the news of the Covid-19 virus outbreak in China first emerged, Samir Saraiya was a worried man. As the founder of one of India's largest companies that deals in what is euphemistically called adult wellness products, it was of direct concern to Saraiya. Like many other products, China is also the factory to the world's sex toys. According to some estimates, around 70 per cent of all sex toys are manufactured in China.

"We were scared, to be honest," Saraiya says. "My fear was we may run out of products in a few months' time."

Saraiya's fears were unfounded. The supply chains of sex toys more than held up. But something no one quite expected lay before him in just a few months' time. The sale of his sex toys went through the roof.

Sales of these products over the years had been on the rise in India. But this was nothing like what was being witnessed once the lockdown was enforced. According to Saraiya, there was at least a 65 per cent jump and it has held up even now. "At some point, we all know, a plateau is coming. But we haven't hit one yet," he says.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

During the pandemic, businesses across sectors went through major disruptions. The sudden change in human behaviour and the value they attached to products overhauled the traditional world of markets. Some of it, like the hoarding of toilet paper rolls, was irrational. But many others, like the crazed buying of foodgrains or packaged food products, was understandable.

Now, before Saraiya, lay a new truth. At a time of devastating sickness and financial ruin, where people had stopped stepping out and begun stockpiling on essentials as though a war loomed, individuals were logging in on Saraiya's website to place record orders for vibrators, fantasy costumes, male pumps, oils, lubricants, and a vast array of adult products too embarrassing to print here.

It wasn't hard for Saraiya to figure out what was happening. Such spikes were being reported by companies elsewhere in the world too.

"Covid-19 opened people up sexually," he says, and offers examples of the record number of Indian visitors to the porn website Pornhub, and the way people have begun to sext. "There was just so much time in people's hands. You couldn't go for a movie. There was hardly any sport on TV. Everyone was just stuck at home. Sex toys, for instance, became a harmless way of enjoying themselves."

What will happen when the world returns to some semblance of normalcy, perhaps with the arrival of vaccines? "There is a famous saying by Alexander Giebel [who owns a lubricant company called pjur] which goes, 'People can eat toast without butter. But the minute you give butter for their toast, from that moment they only want butter on their toast'," says Saraiya.

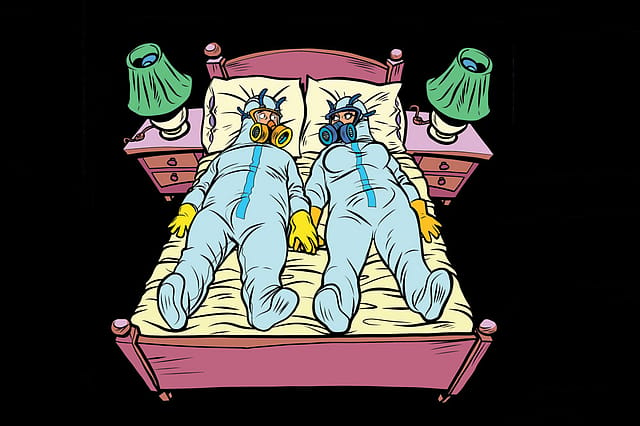

At various points, Covid-19 has appeared to be a virus that does not merely infect our respiratory system and organs, but also one that strikes at love. The nuts-and-bolts of penetrative sex by itself may not be a conduit for the virus, but everything that leads to sex and makes it meaningful is. You cannot kiss each other. You may transmit the virus. You should not touch or caress or cuddle or hug because every such expression may be contaminated. We should preferably only pleasure ourselves, as countless government and health advisories have told us, and when sex becomes unavoidable, wear face masks or assume postures that don't bring us face-to-face. At one point, in the UK, it even became unlawful to have sex with anyone he or she did not live with. And what of the toll all this anxiety and stress exert on us? Have we become more amorous, as Saraiya suggests, or is something more complicated going on?

It is instructive to remember that this is neither the first pandemic, nor the first time sexuality has come under such burden. A US-based website, My Heritage, digging up newspaper archives during the period of the Spanish Flu, found several local anti-kissing ordinances and condemnations of the act both across the US and in some other parts of the world. In one instance, mentioned in Cosmopolitan, a man in Madrid was even arrested for kissing his wife in the street. Some people got around the fears of contagion by kissing through handkerchiefs, and at one point, even an antiseptic 'kissing screen' through which couples could kiss became available in the market.

There is no evidence to tell us what exactly transpired in people's bedrooms during that pandemic. But in this one, the anxiety and the free time—at least in some—have appeared to unlock the doors to our libidinousness. That far from fearing sex, or becoming overwhelmed by anxiety and fear, the virus has unleashed a torrent of desire.

The pandemic's impact on sex, whatever it may be, is understandable. Desire does not rest in our pants. The impulse of sex is located in our minds. And if we know anything from the last nine months, it is that this is a pandemic that equally wrecks our minds.

What Saraiya suggests is an attractive idea. The notion that the virus is ushering in a sexual awakening. And while we must guard against the impulse of extending corporate balance sheets to a permanent change in bedroom habits—people after all are known to respond to stress differently—you can notice that the virus has had an effect on sex. Pornography sites like Pornhub claim there has been a 95 per cent spike in traffic from India, and the most watched shows on OTT platforms throughout the lockdown have constantly shown, apart from a few much-talked about releases, those with adult content. (One of Netflix's breakout global hits this year, including in India, was the terrible Polish erotic film 365 Days, awarded with a 0 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, where a mob boss kidnaps a woman for a year in the hope that she will love him back). Even agony aunt columns in magazines and newspapers were taken over by questions about sex and the virus. And internet message boards, especially Quora, were filled with questions and answers of Indians navigating their sexual lives around the pandemic.

Some, it appears, got plenty; and some got none. Some were locked in, and some locked out. For some, the anxiety of the pandemic crushed any ounce of desire; in others, the same stressor events had the opposite effect. Some ordered adult toys and pushed their sexual boundaries; others climaxed alone in front of a computer screen. Some lost complete interest in sex. Others experienced a burst in desire. And in some couples, both occurred, leading to a discrepancy in desire. All relationships between those that didn't live together, effectively, became a long-distance one. Many had the urge, but no access to a partner. In some, too much access became the problem and came in the way of sex. An office to go to every day or a busy career after all can be an excellent way of impeding the complications of a marriage or relationship from surfacing. But now with work from home, the distracting pleasures of a holiday or movie together taken away, individuals gazed upon their partners in a new light. For some, this could have been good for their marriages. But for a vast many, one suspects, this brought little pleasure.

There were new relationships and breakups, both done and undone online. Some fell in love anew. Others fell out. Couples living away from one another had to explore alternative means of staying intimately and sexually connected; others, whose marriages were going through difficulties, now had to contend with two crises: one raging outside their windows, another inside. One post on Quora states 'we [she and her husband] are fucking like rabbits.' Another says, she and her husband have had no privacy, and on those few occasions when they managed to carve out some private moments, it felt as though they were running late to catch a train. One couple in their late 40s and early 50s tells Dr Mahinder Watsa, in the 'Ask The Sexpert' section in Mumbai Mirror, that they have begun to have sex after a decade, and that the wife now finds herself pregnant. Another, much younger, respondent asks him, if masturbation can increase immunity and if eating onions helps improve sperm count (the answer: 'Not that I know of. Onions, while improving your general health, will also lead to some breath issues which might cause all that sperm going waste.') One married woman in a Times of India relationship Q&A column worries about returning to the office once everyone is called back because of all the flirting she has indulged in while working from home with a male colleague. Another suspects her husband is in touch with an ex-girlfriend. Reading anonymous posts online and responses to agony aunt columns, of course, can be akin to believing the fantasies schoolboys scribble in toilets. But they provide a snapshot, even though a bit unreliable, of the kind of relationship churn wrought by the pandemic.

A study conducted early on during the lockdown and published in Leisure Sciences, which relied on the responses of 1,559 adults in an anonymous online survey, found that a majority of individuals (43.5 per cent) reported a decline in the quality of their sex life, with the remainder reporting that it either stayed the same (42.8 per cent) or improved (13.6 per cent). While many had engaged in mutual masturbation, oral sex and vaginal intercourse in the past year, large numbers (41-61 per cent) had not engaged in any of these behaviours since the pandemic began. A small number of participants also reported increases in sexual behaviour. Approximately, one in five participants (20.3 per cent) reported making a new addition to their sex life since the pandemic began.

The most common new additions included trying new sexual positions, sexting, sending nude photos, sharing sexual fantasies, watching pornography, searching for sex-related information online, having cybersex, and filming oneself masturbating. 'The widespread social restrictions put in place… appear to have significantly disrupted sexual routines and the overall quality of people's sex lives. However, even in the face of these drastic changes, it is apparent that many adults are finding creative ways to adapt their sexual lives, including in the pursuit of sex for leisure,' the researchers write.

Dr Rajan Bhonsle, the honorary professor and head of department of sexual medicine at Mumbai's KEM Hospital and GS Medical College, says the pandemic has affected the sex lives of people differently. Sexual desire, he explains, does not occur spontaneously. It does not just pop out in our consciousness demanding instant attention. Desire arrives from many different underlying motivations and it unfolds in a response to sexual cues. An event, such as a pandemic, muffles or heightens these sexual cues, and even when it leads to desire, the other aspect of the pandemic, the unavailability of a private moment, comes in the way of sex. "In some couples, you find the pressures of managing a house, children and work, and the stress of living through the pandemic has led to a complete falling apart of their sex lives. While for others, this has been a great opportunity. I had patients who wanted to have sex, but never found the time or were always tired. These patients say this period has been such a boon for their personal lives," he says.

There is also a group of people, Bhonsle says, for whom the anxiety of the pandemic has made them more sexual. "It's the case of how some men get an erection while watching a horror movie. Or adolescent boys finding themselves being aroused when a teacher they aren't necessarily attracted to yells at them… Sexuality is quite complicated and a source of stress. It can lead to an unexplained surge in desire in some individuals," he says. "Something like that is happening with a small section of people during this period."

But as exacting—and exhilarating—as the pandemic has been on our sexual lives, it has entirely overturned our conventional notions of romance. I have heard more than one millennial use the term 'slow dating'. But people of a slightly older generation will recall this as simply old-fashioned romance. Sex is now presumably off the table. Necking, kissing is out too. Prospective lovers now want to know each other better. They want to forge real meaningful relationships with whom they can share their innermost feelings. They now write (texts) to each other for months, and when they finally meet, they meet usually at a public place, walk at a measured distance, enquiring graciously about the health of their families.

Snehil Khanor, the CEO of the dating website TrulyMadly, believes casual hook-ups and one-night stands could become a thing of the past. People are looking for more meaningful relationships, he says, and are taking more time to get to know each other before meeting in real life. Before the pandemic, out of every 100 profiles a girl saw on his platform, she would like around 10, he says, and probably begin talking to about five of them. "Out of every 32 men she talked to, she would meet just one of them (on a date)," he says. "Now, she meets just one out of every 50 to 60 men she talks to."

While the pandemic has made dating difficult and fraught with risk, dating websites, however, are reporting a huge surge in online activity. These platforms have tried to help their users navigate the changed romantic landscape by rolling out a range of features that help them meet and conduct their relationships online, from games one can play with each other to introducing video chats. A Tinder spokesperson claims that most people logging in on the platform in India do not necessarily do so to meet a romantic interest. "Tinder as a product does not make you define your intent (when you join the platform). You get to decide what you want from it…We get people joining for a diverse range of reasons. Over 60 per cent are looking to just make a connection. And only about 30 per cent is really looking for love," she says.

A lot of modern romance had been moving online long before the pandemic struck. "The pandemic has simply expedited it," Khanor says. Just like the acceptance around how work can be done remotely, there is also a growing realisation that romance too can be performed remotely.

Aashi Shrivastava, a 21-year-old media student, began to use Tinder when she returned to her house in Bhopal once her college in Mumbai shut down. She didn't want to rush into a relationship, she says. So she took her time. "For a lot of us, what we want from relationships has changed…We have realised the importance of a more meaningful relationship instead of just rushing into things," she says.

There were both more and fewer options for Shrivastava. The pool of people on Tinder, now that more people had joined the platform, was wider. Yet, there was no real option of meeting them on a physical date.

There was an instant spark, she says, with one individual. Over a month of constant chatting transpired before the two decided to date. When they finally met, both wore masks and maintained a distance from one another, she says. They met a few more times, but their relationship eventually fizzled out.

What happened?

"Both of us got bored eventually, I think."