Can Anyone Stop Him?

Donald Trump is the favourite to win America’s looming presidential election

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

James Astill

|

09 Feb, 2024

|

09 Feb, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Trump1.jpg)

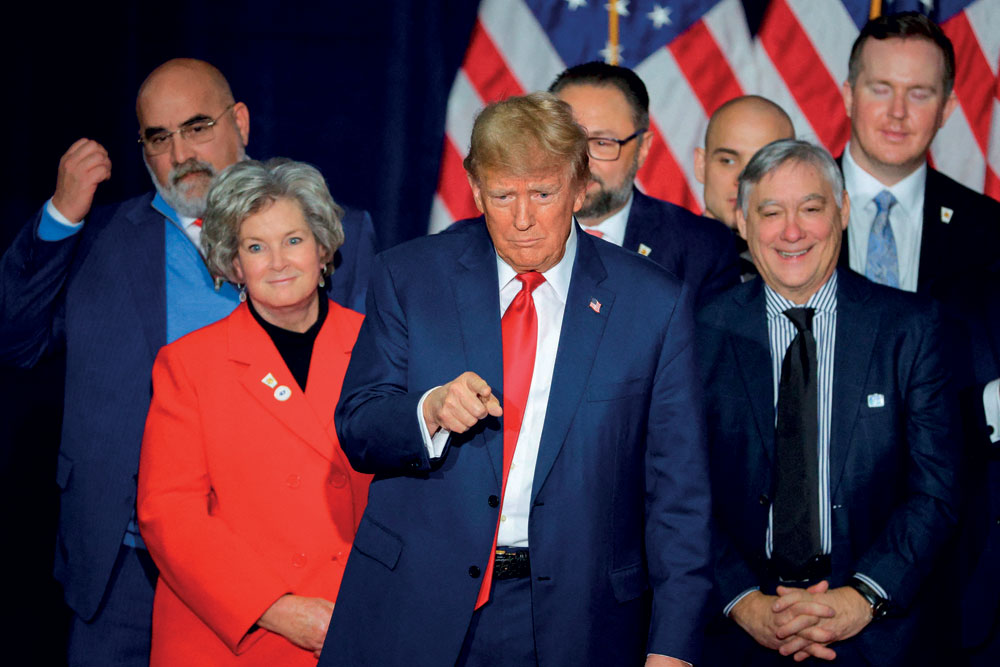

Donald Trump at a campaign rally in New Hampshire, January 16, 2024 (Photo: Getty Images)

GRINDINGLY, SEEMINGLY INEXORABLY, America is heading towards a political rematch that hardly any American wants. Joe Biden, an 81-year-old who seems old for his years, is the most unpopular president at this point in the cycle since surveys began. Yet, defying advice from his fellow Democrats that he should retire, he will, his health allowing, seek re-election in November. His Republican opponent, in a repeat of the Covid-19-blighted and violent contest held in 2020, will be Donald Trump. That is assuming the 77-year-old former president’s heart bears the strain of his steak and cheeseburger diet—and that the courts do not stop him.

The second eventuality is not much easier to predict than the first. Trump is beset by scores of law suits and over 91 felony charges, in four cases, including two federal ones, one in New York, and another in Georgia. They concern his business practices, efforts to overthrow Biden’s electoral victory in 2020, mishandling of classified documents, involvement in hush money payments to a porn-star former lover, and other alleged crimes and misdemeanours. Last month, Trump was ordered by a jury in New York to pay $83.3 million to a journalist, E Jean Carroll, for defaming her. (He had already been ordered to pay Carroll $5m after he was found guilty in a civil case last year of having sexually abused her.)

A judge in New York is meanwhile expected any day to announce the penalty that Trump’s business must pay, after it was found guilty last year of fraudulently inflating the value of its assets by billions of dollars. The city’s attorney general, who prosecuted the case, has asked for a fine of $370m and a ban on Trump conducting business in the state where he made his name. The fact that Trump has called the judge in question, Justice Arthur F Engoron, “deranged” may not help him.

Even for a billionaire such penalties would be painful. And Trump, who is estimated to be worth around $2.5 billion, is a famous penny-pincher. The New York ban, if it transpires, would force him to sell his iconic Manhattan buildings, including Trump Tower. And these are only a couple of his recent legal blows. Last week, a federal court of appeals in Washington DC dismissed his claim to immunity from prosecution for any acts he undertook as president. “Former President has become citizen Trump,” the ruling read, “with all the defences of any other criminal defendant.”

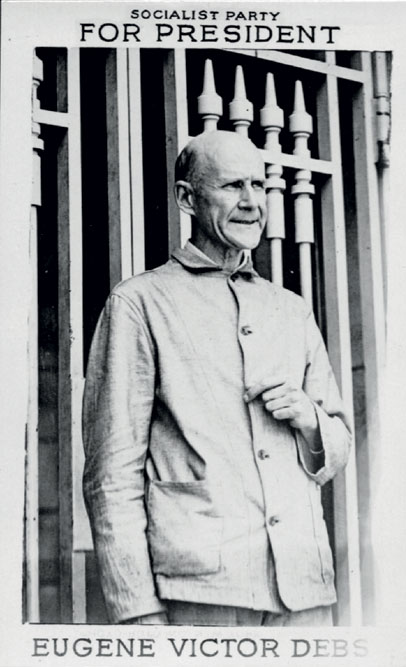

That is among several recent rulings against him that could wind up in the Supreme Court. It may hear the first of them this week—concerning an effort by Colorado to bar Trump from its ballot on the basis that he is an “insurrectionist”. How the court, deeply divided between conservative and liberal jurists, might rule is a matter of hot debate. Yet it is likeliest to try to keep itself outside the political fray, to Trump’s advantage. Indeed, even if he ends up in prison before the election, the law might not prevent him contesting it. Eugene V Debs, a trade unionist from Indiana, famously campaigned for the presidency from a jail cell in 1920. There is no clear constitutional reason why Trump could not emulate him.

What would a second Trump term look like? A more extreme version of the first iteration. Having dispensed with his former mainstream aides Trump would visit more hardline policies upon a more divided America and on a more conflict-ridden world

That is one of several reasons behind a growing conviction, among American newspaper columnists, political operatives and not a few Democratic politicians, that Trump is on his way back to power. Another is that remarkably few Republican voters seem dismayed by that prospect. Trump easily won the first two Republican primary contests, held in Iowa and New Hampshire last month. His presumed main rival, Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, dropped out of the race after Iowa, broke and humiliated, and promptly endorsed Trump. It was clear, he said, that most Republican voters “want to give Donald Trump another chance.” Nikki Haley, the Indian American former governor of South Carolina, the next primary state, is now Trump’s only remaining serious opponent. Betting markets give her around a 9 per cent chance of victory, which seems generous.

Trump’s supercharged fan base was always likely to carry him through the primaries, for which only a small minority of the most politically committed Americans turn out. More surprising is how well he is polling with the general electorate—which is the second big reason why many think he is on his way back. An aggregate of national polls modelled by The Economist gives him a lead of 2.3 percentage points over Biden. And across the half-dozen swing states that will decide the election—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—his lead is bigger, 3.8 points on average. To be sure, the election is still nine months away, and such early polling has a poor record of predicting the winner. But Trump is no ordinary challenger.

HE IS THE FIRST president to have tried to regain the White House in the history of modern polling, which means he is far better known to voters than comparable candidates. Betting markets suggest he is the clear favourite. This puts him in the best position he has ever occupied at this point in an election year. Certainly, he looks far better-placed to win than he did in 2016, when he squeaked a victory over Hillary Clinton, or in 2020, when he lost by a similarly narrow margin to Biden. And this is despite his many mounting scandals—including his disastrous, clownish handling of Covid-19, his support for a bloody insurrection, as well as his legal woes. How is this possible?

Most of the explanation is structural. Despite the microscopic attention paid to rival political strategies and characters in an election season, the reality is that most voters—perhaps 95 per cent of the total—are not up for grabs. And in a freak of partisan arithmetic, these monolithic American vote banks are split fairly evenly. If Trump is the Republican presidential nominee in November he is virtually assured 45 per cent of the vote. The Republican candidate, and for that matter the Democratic one, always is. Only a minority of Republicans, albeit a large one, are hardcore Trump devotees. But if most of the rest do not love the loudmouth populist, they will disapprove of his Democratic opponent more.

Trump’s supercharged fan base was always likely to carry him through the primaries. More surprising is how well he is polling with the general electorate, another big reason why many think he is on his way back

Adding to that advantage, Trump faces in Biden an exceptionally weak incumbent. In 2020, the veteran Democratic moderate was the anti-Trump. His blandness, folksiness and grandfatherly inoffensiveness were accordingly more reassuring than annoying to persuadable voters. But as a leader in tough times, Biden has come across as weak and hapless. That is despite the high plaudits his administration has won on many fronts. Though it had at best only the thinnest of Congressional majorities to work with, it passed major climate and other legislation in 2021-22. In foreign policy, it has been forthright and at times successful. It was quick to mobilise the Western coalition to defend Ukraine against Vladimir Putin. It is now battling to prevent the war in Gaza spiralling into a regional conflagration. Much good has this done it politically.

When Americans are feeling the pinch, as in recent years they have due to high inflation and other pandemic aftershocks, they blame the president. And Biden’s manifest weakness, as an elderly politician prone to meandering thoughts and embarrassing memory lapses, has made them all the more contemptuous. Ominously for his party, Biden is polled especially badly with groups that are considered essential to the Democratic coalition, including Hispanics and younger voters. Unless he can turn this around, he risks leading his party to a crushing defeat.

There are a few signs that the race could yet turn in his favour. Trump’s lead in the swing states has faded slightly in recent weeks. Analysis by The Economist also suggests that the pollsters with the strongest track records are finding slightly more support for Biden than the industry average. Moreover, the economic fundamentals, which have weighed heavily on his presidency, could yet do him a favour. America’s economy is growing faster than that of any other G7 country, buoyed by a strong labour market and household spending. Inflation is meanwhile falling rapidly, raising a prospect of interest rate cuts and cheaper mortgages. If Biden is lucky—and it would make a change—he may find himself presiding over a ‘Goldilocks economy’, neither too hot nor too cold, by the time of the election.

But even in that case no one should discount Trump’s chances. America’s national elections are only a little more loaded than a coin toss. So, it is necessary to ask, what would a second Trump term look like?

According to the former president’s advisers and public statements, it would be a more extreme version of the first iteration. Having dispensed with his former mainstream aides—the retired generals and Wall Street types that staffed his first administration—Trump would visit more hardline policies upon a more divided America and on a more turbulent and conflict-ridden world.

He has pledged “on day one” to close America’s southern border with Mexico. After basking in the diplomatic, economic and humanitarian chaos that would then certainly ensue, he would no doubt set about juicing the economy, one of his first priorities last time round. He has promised to make permanent and increase the tax cuts he passed in 2017. A self-styled “king of debt”, he has no interest in prudence: America’s enormous deficit would yawn and growth perhaps tick up.

An aggregate of national polls modelled by The Economist gives Trump a lead of 2.3 percentage points over Biden. And across the half-dozen swing states that will decide the election—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—his lead is bigger, 3.8 points on average

HE WOULD ALSO double down on the import tariffs he imposed in his first term—the most by any president in almost a century. “I am a Tariff Man,” he once famously declared. He is said to be mulling an across-the-board levy of 10 per cent on all products entering America. This would more than triple the average American tariff, representing a steep tax on American consumers. It would also do terrible damage to America’s alliances—undoing in a single blow a lot of remedial work undertaken by the Biden administration. America’s adversaries would revel in that. But they would also suffer. Trump is also said to be mulling an effective suspension of “normal trade relations” with China.

When he first took a wrecking ball to America’s trade ties, a few Republican Senators demurred. The party had for decades been in favour of free trade, after all. Trump would encounter little or no repeat resistance from his party. Its former Trump sceptics have been terrorised into silence or driven from politics. Mitt Romney, a former presidential candidate and the only Republican Senator to vote against Trump in two impeachment proceedings, will retire this year. This would assure Trump of Republican acquiescence to even more controversial measures.

He would almost certainly end America’s support to Ukraine. This week, House Republicans provided a foretaste of that by refusing to vote for a deal—though they had long demanded it—which would have married increased border security with fresh funding for Ukraine. Having left America’s European allies in the lurch over Ukraine, Trump would probably then go a couple of steps further, and withdraw America from NATO. Already badly degraded, the post-1945 American-led order might then be considered over.

Even if Trump ends up in prison, the law might not prevent him from contesting. Eugene V Debs famously campaigned for the presidency from a jail cell in 1920. There is no constitutional reason why Trump could not emulate him

What would India and the many countries neither of the West nor pro-China make of this dissolution? Some would find advantages in the more ad hoc trade and other partnerships it would give rise to. India, given its economic heft and history of vigorous non-alignment, would be especially well-placed. But the destabilising effect of an abrupt American retreat from global leadership under Trump would be widespread and immense. Even America’s adversaries must look on that prospect with a certain trepidation.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba