Lawrence Osborne: ‘Sensuality drives everything in travel’

Novelist and traveller Lawrence Osborne on the art of seeing and writing

Tunku Varadarajan

Tunku Varadarajan

Tunku Varadarajan

Tunku Varadarajan

|

03 May, 2018

|

03 May, 2018

/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Sensuality.jpg)

LAWRENCE OSBORNE IS 59, but he’d clocked just 50 when a mutual friend brought him to my home for dinner one night, the first of many meals my wife cooked for him. A tall Englishman who left his shirt-front largely unbuttoned, he supped with notable gusto (he was always “starving”) and had a mad laugh that was a mimic’s delight. He told everyone he was a novelist, and he certainly had the air and charm of one (along with an actual, if forgotten, novel published in 1986). But he was more widely known as a travel writer, living off commissions from glossy magazines that sent him first-class to a host of enviable destinations. In 2011, he published Bangkok Days, an uninhibited account of a visit to the Thai capital, where he’d gone as a ‘dental tourist’ to get his teeth fixed cheaply but ended up having his mind blown by the city’s attractions. Soon after that book was done, he fled New York, telling his friends that America’s sterility was killing him. There followed a short stint in Istanbul, where he wrote in an old house atop a hill, before he moved to Bangkok. He lives there serenely and writes like a fiend. He has written four novels in the last five years, The Forgiven—from 2013—being particularly lauded. He’s also resurrected Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s private investigator, in a novel to be published in July. I caught up with Osborne by email—he in Bangkok, I in Brooklyn—and the following friendly conversation ensued.

Lawrence, you’re a writer who travels—a ‘travel writer’, even. Do you like the term? Is it useful, or is it hackneyed?

I think it’s a dated term which no longer holds much appeal, not to me anyway. We no longer live in the world of Eric Ambler or Norman Lewis, or even Bruce Chatwin. I suppose you could walk from London to Istanbul like Patrick Leigh Fermor did, but today it would just be a stunt and it wouldn’t be particularly interesting. Would you like to walk across Bulgaria? I don’t think I would. The world has been changed by its transportation systems and its cultures thrown together by the medias we all share. My last ‘travel piece’ was for the New Yorker back in 2005, for whom I trudged across forests in Irian Jaya. That was radical travel of a sort, but I was never quite sure how authentic it all was. I was glad to see the Kombai tribe’s culture close- up, but I was almost sad to have to write about it in a magazine as glib as the New Yorker. I think it was then that I decided to drop the idea of ‘travel writing’ and just concentrate on travelling, so to speak, through my own worlds—in fiction.

‘We are a migratory species. We like to wander the earth and find out what other humans are up to’

Is the problem that writing—like travel itself— has become something that too many people do? Is it possible to say that travel, like writing, actually requires a certain talent?

That’s an interesting, if heretical, observation. But yes, travel requires maybe even more talent than writing, as shown by how few people can actually do it with the requisite originality. I am far from excusing myself in that regard. I have become a tremendously irritable, contemptuous, harried traveller, constantly cursing my fellow travellers, who are of course just vacationers, not travellers, and increasingly isolated inside my own need to be alone, to have a comfortable spot, to not be submerged in the vast Chinese tour groups who now make moving around even Thailand a torment. Naturally, I have a fair point. The whole thing has become a farce.

How do you differentiate ‘vacation’ from ‘travel’?

As Paul Bowles used to say, more or less, the vacationer is just passing through, the traveller comes to stay… for a while at least

So, when you travel to a place, you seek to ‘stay’ in some way. I assume that means immersing yourself in the place, becoming a part of it. What are the things you do to make that happen… to belong?

I would say that it is quite a mysterious desire, to linger like that—it would certainly be easy to caricature it as ‘orientalist’—a stupid phrase derived, in my opinion, from a mediocre book. Whenever people start droning on about ‘orientalism’, I refer to them to the brilliant counter-argument of the scholar Ibn Warraq, who demolishes Edward Said quite easily. No, the desire to linger outside of your own culture is hardly a reprehensible thing; it’s a gesture of the imagination which reaches out to the human communality. I find it more enigmatic and subtle than one might think. I have no idea why I feel ‘at home’, for example, in Southeast Asia, or Japan, whereas I detest California, the south of France and Surrey. Do I not have the liberty to make such elective choices, which in the end come down to temperament and sensibility? Some would say not. But to hell with them, it’s my life and I can spend it as and where I wish. We are a migratory species. We like to wander the earth and find out what other humans, probably as awful as ourselves, are up to.

Let me press you on that last answer. Why exactly do you feel at home in Southeast Asia? After all, you’ve lived in Bangkok for some five years now. You used to call New York home, but you fled from there to Bangkok. You must have known what was awaiting you, and also what you were fleeing from.

I had a rather clear idea, but then again I found that I didn’t know Thailand quite as well as I thought I did. As soon as I arrived, there was a military coup. But every society has its dark side, and Thailand is no exception. That’s the human equation. I certainly knew what I was leaving in New York—an increasingly unliveable, insanely expensive mad-house. But that’s just my view of it after living there for 20 years. I think it’s a young person’s city. Past a certain age, it’s just exhausting and not very pleasurable. You know, eventually you have to live where it’s pleasurable for you—it’s not a frivolous demand, when you think about it. I often wonder if I like Asia because people have better manners and, on an interpersonal level, more consideration for others; plenty of garrulous expats will snort and stamp their feet if you say this, but then why are they not living in their homelands if they feel this way?

I realise I am not working-class Thai, living in a slum—but then, nor are most Thais. We are seeing the emergence of relatively sophisticated societies all over the world which in the end are not particularly exotic when it comes to day-to-day life. I don’t walk around in a sarong all day and eat off banana leaves—I go to my local espresso bar and eat croissants and drive my motorbike to a luxury mall. It’s not a postcard from the ‘developing world’. I hate that phrase, too, by the way. In many ways, I find Bangkok more sophisticated than some aspects of New York. I think more and more people will realise this when they actually get out of their Western bubble and live elsewhere. They won’t, of course. But as Buddha says, look to your own salvation, not that of others. I think he says that, anyway.

Is travel—and, by extension, living—about salvation? It used to be about adventure once upon a time. Or is adventure overrated?

Adventure is for adolescents. Salvation, on the other hand, is an adult’s life-work. I have no desire whatsoever for adventures at this point of my life. I go to Mongolia whenever I can to get in some horse-riding and archery, but not because it’s adventurous—it isn’t particularly. I just enjoy the Gobi and firing missiles at straw targets!

Tell me about the things that make you love a place, that pave the way to salvation. Food? Drink? Language? Local people?

One’s own preferences are not logical or obvious to oneself. Maybe it’s things we are not entirely conscious of: climate; the subtle effects of a cuisine; a sexual or aesthetic thing; or else how you are able to live day to day. If you look at the world only politically, you may as well stay home and go on marches. Inexcusably or not, it’s not my thing. I wouldn’t go on marches anyway. Most of what we call ‘politics’ is nothing of the sort. It’s way more pathological and preening than we’d care to admit. And then, the writer—being alone with no resources—has other concerns. Silence, exile, cunning, and all that. I have no family money, no back-up—I have to survive on my wits, and always did. Most writers— most leftists too—come from the upper-middle- class and don’t have this problem. For me, it’s a severe one. So, inevitably, I will gravitate to a place where I can stop worrying about how to survive and make rent. I decided I wanted to write novels without interruption and living in a place like London is out of the question now, as far as that is concerned. So perhaps these mundane considerations have added to the charm of a place like Bangkok. However, in the end, these are animal decisions, not really intellectual ones. I’m not trying to make some abstract point; I’m trying to have a platform upon which I can devote myself to the art I’ve chosen. It sounds a little precious, I know, but that’s just the fact of the matter. And then, there are moments almost every day here where I feel the beautiful spirit of the place—a thousand intangible things which remind me of how much I enjoy living here day by day. The everyday dabs of human beauty (and ugliness).

And sensuality?

I think sensuality drives everything in travel, and always has done. Not always consciously, but usually consciously. We just don’t want to talk about it publicly. The most sensual places are invariably the places where you are attracted to people sexually, despite all the other contingencies. For me—and I don’t want to have to explain the whys, because I can’t—that would be India, the Middle East, Southeast and East Asia. The rest of the world, strangely, has no sensuality for me. Perhaps I should try psychoanalysis.

Is Thailand the most ‘liveable’ place you’ve been—and Bangkok the most ‘liveable’ city? And while I’m at it: may I ask if you find the West unliveable-in for reasons other than expense and high cost? Do you have aesthetic objections to the Western life that’s currently on offer?

‘Liveable’ is a relative term. It depends on which city, which neighbourhood, which friends you have, and so on. But yes, for me personally it is the case. And it’s not just a question of costs—Bangkok is not especially cheap these days, alas.

As for the Western lifestyle, I think it’s becoming less and less appealing—when you consider the strange paradoxes of a country like Britain, a pioneer of democracy descending into a sort of surveillance nanny state. Yes, Thailand is that too, but the surveillance is so incompetent and half-hearted that you are just left alone and the concept of a nanny state isn’t nearly as effective. The military just aren’t that good at it. Bangkok is delightful anarchy compared to the anal ‘health and safety’ manias of contemporary Britain. But perhaps that’s how the British like it. It’s been said that Britain is a country where everything is policed except crime itself. Here in Bangkok, the authorities are always trying to ‘clean up’ this and that (street food, night life, etcetera ), but they never seem to succeed very well. Many people lament this. Not me. There’s more vibrant street life within four blocks of where I live than in the whole of Brooklyn. And so it’s easier for someone like me to be alone.

What draws you to Japan, of which you’ve written so much?

For me, Japan is a special place. I am married into a Japanese family via my son, so I am seen as a ‘giri no Otosan’ (father-in-law) there and the word ‘giri’ in Japanese implies some kind of social responsibility—which is reciprocated by respect for the young. Japan respects age and the old. Youth-culture tyranny is vile and fascistic. Japan has a youth culture, but it also has an age culture. That is why they live longer than anyone on earth. All the criticisms one reads of Japan (almost entirely written by Western journalists, I might add) never manage to see ‘around’ the whole culture—which has vertical depth in vast abundance. Only Japanese has a word for ‘the effects of sunlight filtering through trees’—komorebi —or a concept like wabi-sabi, originally derived from a word for loneliness and now meaning the melancholy that emanates from objects made beautifully imperfect by time.

Of course, they have ‘speedu freaku’ as well, but that is the wonderful syncretism of a culture which is otherwise homogenous. But in Japan the homogeneity never seems sterile to me, as it does in some other places. I love the mad pursuit of artisanal perfection, the way thousands of tiny, exquisite retail spaces are piled up in equally tiny streets but without confusion or squalor. I love the respect people have for their own work, and the near total absence of crime. The way, after Fukushima and the deaths of thousands of people, people lined up patiently for water and committed not a single act of looting. Yes, it’s overcrowded, neurotic, marred by horrible modern development, and quirky. But I fall for its fading glamour and its highly literate and refined culture— which you can see in its cinematic masterpieces. Are there any films greater and more profound that those of Ozu, Mitzugouchi, Kurosawa and Kobayashi? Not on my planet. And even in contemporary cinema, I am a great follower of Kiyoshi Kurosawa and Kitano, Yoji Yamada and the new young director Kei Ichikawa. Those are my reasons—we’ll talk about the world’s best food another time.

And India? You’ve been there often. How do you regard it as a place to be in—its people, its ways, its foibles?

Well, India is emotionally complicated for us English, for so many reasons. I have more Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi friends than Thai in the literary area—the relationship is intellectually closer. When I’ve been in India it has been for things I’ve wanted to ‘submerge’ into, whether it be the Ajanta caves or the temples around Somnathpur or the Andaman Islands, a place I love. I love Calcutta and go there when I can, since it’s only two hours away from Bangkok. I have a great fondness for Leh and Ladakh. But on the subject of mangoes we will probably have to agree to disagree on the relative merits of the Thai and Indian versions.

I’m not going there! But, do the English and the Indians have a special affinity for each other?

Yes, they do. Their relationship to the written word is very similar, for one thing; how else would Indian writers have entered the British canon so majestically? It’s very possible that the British were as much transformed by India as the other way around. I’ve always wondered—perhaps whimsically—if there are subconscious reasons that I like the Buddhist- Hindu mix in Thailand (whose king, let’s recall, is an incarnation of Vishnu). At the very least, you can say that the British psyche, to put it a certain way, has been altered by the Hindu world, and is consequently rather open to it. We have always thought India was a little special in some indefinable way, and many of us still think that.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

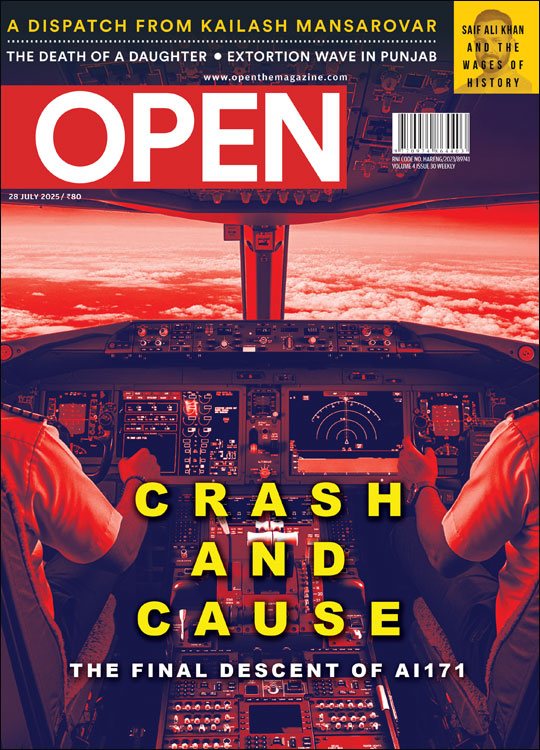

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba