What’s At Stake?

Anyone seen a pandemic lately? Not in Bengal. The long and circuitous journey from Kolkata through Bantalabajaar, Ghatakpukur, Bhangor, Minakha, Bidhyadhari, Bashirhat, Taki, Deganga, Barasat—and along the Grand Trunk Road in Hooghly district over the Easter weekend on the following day—was alive with the bustle of roadside commerce, overlaid by the excitement of another election. The one thing in common across differences of human age, gender, profession, caste and faith was that no one wore a mask.

Is politics the vaccine of Bengal?

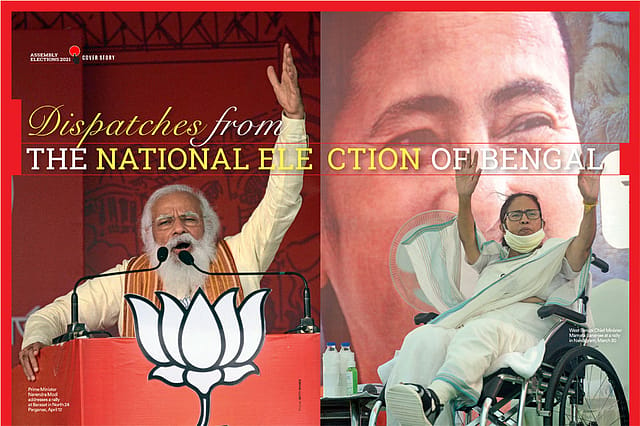

There was a second surprise. For some inexplicable reason, there were no hoardings of the principal vote-winner for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Prime Minister Narendra Modi, outside Kolkata and its immediate, contiguous suburbs. If development is the antithesis of Mamata Banerjee's decade in power, then for BJP Narendra Modi is the one magnet which can make the voter switch. The only rational explanation is that BJP had left the heavy artillery of its campaign for the final phase; there was still a week or more left before voting in the region we had traversed.

The 65 constituencies of densely populated South and North 24 Parganas constitute a formidable bloc within the Bengal Assembly. Once upon a time, two-and-a-half centuries ago, these Parganas wrote the opening chapter of a new history book. They were the first revenue districts which the East India Company received as the prize for Robert Clive's famous victory over Siraj ud-Daulah at Plassey in 1757. They became the economic base which financed the growth of the Company's realms, and hence a launchpad of Britain's formidable Indian Empire. The Raj thanked 24 Parganas with a canal. We drove alongside this canal till it gave way to water bodies known as bheris, water farms which supply the hungry markets of Kolkata mainly with insatiable quantities of prawn.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Fish is both the sustenance and symbol of Bengal. The delectable Ilish, or Hilsa, is a delicacy beyond the confines of sects and borders; its many recipes are the pride of every kitchen. A Bengali child learns very quickly, from a combination of necessity and instinct, to separate the sharp and potentially dangerous needle-spine bones from fish flesh in the mouth, for they can slip through the web of fingers while being eaten with rice. Fish is a staple of the diet. Fish, according to worldwide lore, is good for the brain; for the Bengali mother getting her daughter or son ready for a school examination the intellectual efficacy of maachher jhol (a thin fish gravy) is inherited fact, not supposition. You will not easily find a vegetarian in Bengal.

Food, poetry, music and spontaneous wit, the essence of adda, or chat, define the unique ambience of Bengal. Language and culture subsume, although they do not eliminate, differences of faith. The political history of the British period and its final scalpel cut through the heart of India. Partition injured this cultural homogeneity, but not fatally; it survived the assault. A quarter century after 1947, the tsunami power of the Bengali language channelled an emotional mass upsurge which culminated in the liberation of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971.

The intonation and dialect of Bengali differ between eastern and western Bengal, but there is nothing called 'Muslim Bengali' and 'Hindu Bengali'. Every Bengali shares the power of a common poetry; the national anthem of Bangladesh is a paean written by Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore. The British did their best to destroy this amity, in ways blatant as well as subtle. One of their more nefarious decisions was to create separate drinking water facilities at railway platforms, which they labelled 'Hindu paani' and 'Muslim paani'. But there is no 'Hindu' or 'Muslim' in the music of boatmen or the language of the village. Bengalis take pride in this culture.

Unsurprisingly, one man who recognised and defended the difference was Mahatma Gandhi, the wise father of modern India who understood the multi-throb heart of his countrymen better than anyone else. Gandhi was a fierce vegetarian; indeed, he took minimalism to new levels, sometimes subsisting only on nuts, and describing himself as a "nutarian". During the lethal winter of 1946-1947 this smiling, sagacious, toothless apostle of non-violence went on an epic four-month mission to heal communal wounds in Noakhali, on the eastern fringe of united Bengal. As an exercise in self-abnegation, he had reduced his diet to two sparse meals a day. His early lunch consisted of eight ounces of goat's milk, an ounce of fresh lime and a vegetable paste without salt, spice or oil which others in his small band found decidedly inedible.

A Bengali academic in Gandhi's entourage could hardly be blamed when he sidestepped the puritan fare of the travelling kitchen, and ate the appetising local fish. Word spread. A journalist mischievously asked the Mahatma if killing fish did not amount to violence. Gandhi replied that Bengal was a land of water, so where was the harm in anyone eating fish? In any case, he added tartly, eating fish was less harmful than the damage human beings inflicted by selling adulterated food.

New borders do not change the physiognomy of people. Bengalis in South 24 Parganas, stretching down south to the Sundarbans, look and dress like their counterparts in the east. Two-thirds of the Sundarbans is in Bangladesh. Sundar-ban is not the Bengali term for a beautiful (sundar) forest (ban); it comes from the large and plentiful mangrove Sundari trees within the 10,000 square kilometres of saltwater and soil between the Meghna and the Hooghly estuaries as these beautiful and vivacious rivers decant the waters of the Brahmaputra and the Ganga into the Bay of Bengal.

In dress, however, you might begin to differentiate between Hindus and Muslims. Middle-aged Muslim men wear the lungi (derived from the longyi, the national dress of Burma) and sport a thin straggle of a beard; women drape their saris over the head. Hindu men wear the normal pyjama and on formal occasions the dhuti. But common traditions are equally evident.

Names spill across religion. Rufika Mondal is a Muslim candidate for Trinamool from North 24 Parganas; Mondal is the pre-Islamic caste name, and still a source of her social identity. At Paglahaat, Mustafa Molla advertises his sweetmeat shop as a boon from 'Maayer Aashirvad' (Mother's Blessings; there is implicit duality here, for mother can refer to both a birth mother and Ma Durga). The Annapurna Hindu Hotel nestles in the vicinity of biryani outlets. In Ghatakpukur, the Haji Royal Biryani makes clear on the signboard that there is no beef in the biryani. Other mini-restaurants or food outlets prefer silence on the subject.

There are some, albeit stray, signs of marginal upward economic mobility. The Frozen Garden Village Resort, off the highway, is beyond the means of still-meagre rural incomes, but within the reach of Kolkata gentry who have to drive just an hour for a staycation. A tannery built on modern lines at Bantala has become the new home of the old, and odorous, leather workshops in Kolkata's Tangra locality. The City English School at Chandipur speaks to those in rural Bengal who aspire to join the Big Town.

Party flags and slogans are generally located in a cluster around the election office; but if buntings were to determine the race, then Mamata Banerjee would be far ahead. However, this district is her stronghold, which she retained even during the General Election of 2019.

A big gate has come up on the main road (not quite a highway yet) in the name of Twaha Siddiqui, a descendant of the pir, or saint, Hazrat Abu Baqar Siddique (1846-1939), whose shrine at Furfura Sharif in Hooghly district is considered by his followers as second in sanctity only to Ajmer Sharif in Rajasthan. His five sons are also buried there, giving it an alternative name: Panch Huzur Keblah. Hazrat Abu Baqar is revered for social reform, charitable orphanages and schools, including, famously, a school for girls. His famous shrine dominated the headlines for a few days at the start of this election when one of the family, Abbas Siddiqui, joined the Secular Front set up by the Marxists and Congress. Twaha Siddiqui has remained loyal to Mamata Banerjee; hence the celebratory gate with his picture in Trinamool territory.

The economic landscape does not improve until we near Bashirhat and Taki, where crowded markets display modern utilities like Korean refrigerators, and smaller shops offer savouries and India-made household essentials which will end up being sold at a higher price for villagers with lower incomes. Such are the practical sinews of capitalism.

Taki has a government school with a sturdy building and spacious compound, a public library, a bookshop named Gitanjali Pustakalaya, at least one hostelry for visitors (Indian Guest House), and medicine shops with ebullient nomenclatures like Remedy Zone. A 'Make-Up Artist', Mini Ghosh, offers her skills through an advertising poster.

The new attraction in town is a modern resort on the banks of the Ichamati river, which has filled up with guests on a weekend break. The holiday shrieks of children running through the lobby as parents go through the sanitised check-in procedure rise above the adult murmur like sharp punctuation marks. The playground scream is duplicated in the café on the first floor, where the aroma of fish, alongside the spiced up kosha mangsho, a favourite recipe for mutton, rises above the buffet. The semi-busy staff look very relieved at the return of work. Outside, autorickshaws wait to take customers to the riverside for an hour's boat-ride. In theory, the boats must stick to their half of the Ichamati, for the middle of the river is an international border.

Across the river is Bangladesh. A few country boats sit quietly on the further shore, waiting for no one. Immediately to our left is an outpost of the Border Security Force, guarding the midway demarcation of Ichamati. But no river can be fenced. The ambit of any guard is not unlimited. If the people on both sides of the divide continue to live peacefully in their own villages, it is because they want to, not because they are forced to.

We sit under a shelter on our bank, watching the silent drama of a river flowing by. Gradually the eyes adjust through the sunlight to the strength of the undertow, in either the surface movement of water or the occasional bit of flotsam. This is a clean river. And then you notice that there is more than one current in its belly as it interacts with searching tides from the Bay of Bengal. Currents can run parallel and boatmen know which precise line will pull in their direction as they navigate their goods or passengers.

It is tempting to use this image as a metaphor for the Bengal elections. Many currents are in play, and voters are selecting parallel routes to their preferred destinations. The essence of these Assembly elections can be pared down to two questions.

BJP asks the voter a simple question: Do you want any more of Mamata Banerjee?

Mamata Banerjee has a counter question: Do you want any of BJP?

Contrary to reputation, Bengali voters are patient. They gave Congress two decades in office before turning it out in 1967. This was followed by an uncertain decade divided between the four troubled years of non-Congress coalition governments, and five years of a militant Congress led by Siddhartha Shankar Ray. In the summer of 1977, with Emergency over, Jyoti Basu's Marxists were elected, a little to their own surprise. No party has made better use of opportunity than the Marxists. Bengal saw almost 35 years of unprecedented stability before voters pushed the eject button. Observers have generally attributed such longevity to the Marxist cadre and its violence-coated electoral machinery. In politics, a machine can do 10 per cent of the heavy lifting. The rest depends on popular support, which is determined by more substantive factors like social and economic welfare.

Jyoti Basu did not survive on charisma, whim or smile; he won five consecutive elections thanks to a radical policy which earned Marxists a lifetime's gratitude from the peasantry. Operation Barga introduced reforms which gave the cultivator ownership of land and better irrigation, raising rural incomes. From 1977 till 2000, or all through Jyoti Basu's leadership, Bengal's per capita income remained on an upward curve, not fully on par with the average for the whole of India, but still growing at a similar rate. This positive graph began to slide after 2004 because the rural economy alone could not satisfy the aspirations of a generation seeking its first jobs in the 21st century.

While Basu himself was largely amenable to the economic reforms initiated by Prime Minister Narasimha Rao in the early 1990s, he faced entrenched resistance from doctrinaire elements within the Communist Party of India-Marxist (CPM) politburo, who were convinced that all intellectual innovation had stopped with Stalin. With so many competing Indian state governments offering a red-carpet welcome, industry kept out of the Left Front's frayed and union-dominated environment. Jyoti Basu's successor Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee had a decade in which to regenerate industry. He could not. The Marxists were crushed by Mamata Banerjee in 2011. Bengal, which had been in the forefront of industrialisation till the 1960s, lost out. Over the 30-year period from 1991, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka have recorded twice as much industrial growth as Bengal.

But these three decades have included 10 years of Mamata Banerjee. She promised dramatic change and all that the people saw was a different name on the chief minister's cabin. If the Trinamool Congress (TMC) is vulnerable it is because the gap in per capita income between Bengal and the rest of India has increased in the last 10 years. Bengal's figure was Rs 58,195 against India's average of Rs 70,893 in 2012-2013; it is now Rs 1,15,748 vis-à-vis Rs 1,35,050. An average figure is never the real story. The gap grows when you compare the incomes of the poor.

Bengal's lag arises primarily from the lack of industrial investment. This rising disenchantment was reflected in the elections of 2019, when BJP exceeded expectations while winning seats along the industrial spines of Bengal which run on parallel lines along both the banks of the Hooghly. These industries, begun during the British Raj, were enhanced by Indian industrialists after Independence.

The young are not motivated by agriculture; they want jobs. For obvious reasons, Mamata Banerjee avoids economics and development in her election speeches. Instead, she positions BJP as the "outsider" with an unacceptable veneer. The irony is that her evidence comes from those who turned their coats on the eve of the polls. Suvendu Adhikari, her opponent in Nandigram and once her handpicked party stalwart, described Muslims in Nandigram as "Pakistanis" and declared that he did not want their votes. Not that he was getting them anyway; but his toxic accusations helped consolidate Muslim voters in Mamata Banerjee's favour.

It does not take too much conversation to recognise voters who still want to vote for Trinamool. They willingly concede that there has been rampant corruption, but then offer an alibi: henchmen took the loot, and the crooks have all left. It is a thin alibi. Let's call it the entrée of survival fare in the last-chance saloon. A reputation for endemic, down-the-line corruption is the single biggest negative that Mamata Banerjee must overcome, or at least elude, in order to survive.

The Bengal voter may be patient, but when that patience is exhausted, the shift is decisive, as it was in 1967, 1977 and 2011. Congress was broken in 1967, and its temporary restoration between 1972 and 1977 was due only to Indira Gandhi's sharp rise in popularity after the liberation of Bangladesh in December 1971. The Left was crushed in 2011; today the remnants of Congress and the Left are barely visible in the debris of electoral politics.

BJP is bolstered by three factors: a visible urge for change; the strong base it has built through a dedicated cadre among backward castes and communities; and a general feeling that Mamata Banerjee has indulged in appeasement of Muslims. There is palpable support for BJP among voters with sectoral interests to project or defend, like the Matua community.

Conversely, Mamata Banerjee has a virtual lock on the Muslim vote, and retains some of her popularity with women. Playing the "outsider" card, she tags her opponents as more loyal to Delhi than to Bengal. Since wit is endemic to Kolkata's political discourse, those who normally live outside Bengal have been dubbed "Dalda Bengalis", as opposed to the "real ghee" of homegrown candidates.

The stakes in 2021 are high, which is why the battle is so keen. This election will determine, at an obvious level, who forms the next government in Kolkata; but it will also have implications for the developing battle for the next General Election. If the script runs along BJP's expectations, then the party will have taken a tremendous stride towards its objective of an all-India footprint, in addition to governing a state widely considered beyond its reach. Indeed, any number in three figures for the party constitutes a massive advance, given that BJP got only three Assembly seats five years ago. If Mamata Banerjee's projection is accurate, then she will take her first credible step towards a national role. Non-BJP parties are inhibited by the absence of a leader who can hold a coalition together. Their search could pause with the relentless Mamata Banerjee.

Rahul Gandhi does not cut the mustard. Thanks to his uncertain grasp of governance, and inability to understand the grammar of political language, Congress is mired in fragile territory. It does not require any secret intelligence to suggest that Mamata Banerjee will try and displace him from the central space.

It used to be said that when Bengal sneezes India catches a cold. We might have to amend that. When Bengal catches political fever, Indian politics heats up.