The Last Mutiny

It’s the 75th anniversary of the naval insurrection that shook the empire. It’s also the story of how the rebellious sailors of the Royal Indian Navy were let down by a divided political leadership

Pramod Kapoor

Pramod Kapoor

Pramod Kapoor

Pramod Kapoor

|

12 Feb, 2021

|

12 Feb, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Mutiny.jpg)

HMIS Hindustan, a cruiser that mutinying naval ratings abandoned in Karachi on February 20, 1946 (Photo: Alamy)

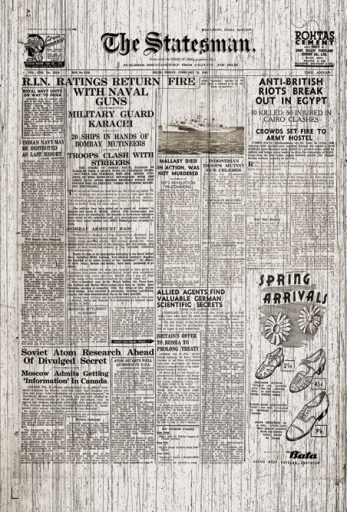

February 18th marks the 75th anniversary of the Indian naval mutiny. Although this episode is ranked among the many that make up the saga of Indian independence, it was one subverted by politics. Even as ordinary Indians came out in thousands onto the streets in solidarity, Congress leaders actively mediated only so that the naval ratings who had struck work and rebelled would give themselves up without any of their demands being met. They saw in any success of the mutiny a threat to their political future as rulers of independent India. The mutiny lasted four days but a handful of sailors had by then brought the might of the British Empire to its knees. Or, at least, in a post-World War II era, showed them the tenuous hold they had over their colonies. It perhaps precipitated the British departure from India because they could no longer depend on their armed forces to be loyal. The men who mutinied got only punishment for their participation but their reward was in changing the final tempo of the freedom movement.

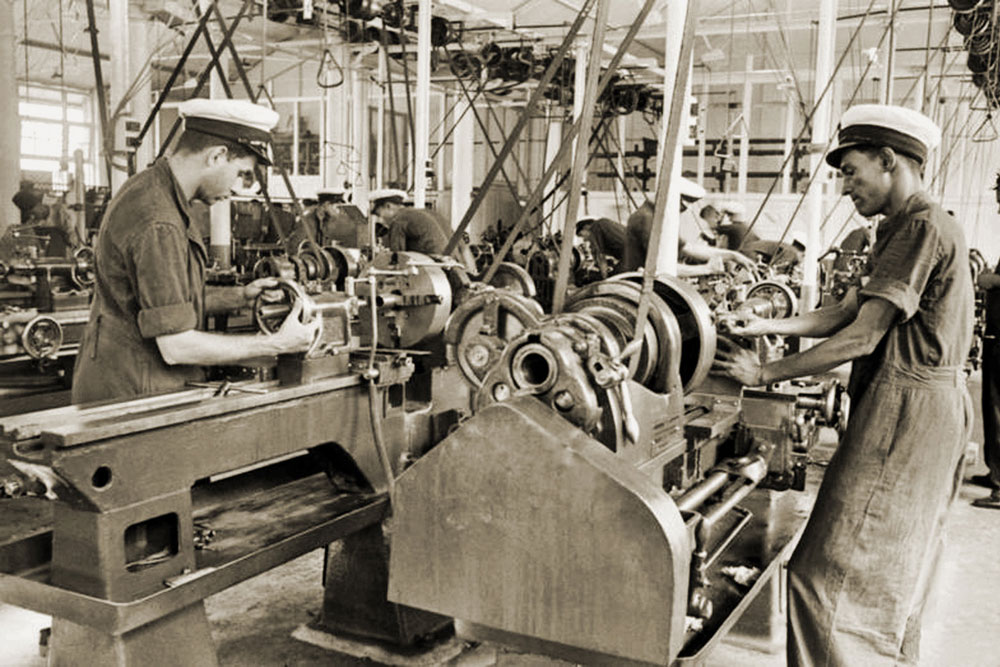

IT WAS THE MIDDLE OF February 1946, and Bombay’s residents going about their normal business had no idea of the storm that was brewing in their midst. It would engulf them in a mutiny, riots, cannon and gunfire, tanks on the streets, a deadly body count and a confrontation with British authorities that would shake the foundations of the Empire. It would also cause deep divisions in the Indian political leadership, then busy planning for a smooth transition of power. The first sign of the impending uprising came, appropriately enough, at the HMIS Talwar, a signal school for naval ratings in Colaba. A strategically important naval establishment for British forces in India, Talwar became the platform for the launch of the mutiny. There were close to 20,000 young Indian naval ratings who had been subjected to the most degrading and inhuman service conditions, and their anger and frustration had reached boiling point, fuelled further by the nationalist movement and stories of resistance by the Indian National Army (INA).

The movement would involve Indian ratings posted in ship and shore establishments in the Bombay area as well as ports as far off as Karachi and Aden. For four days and nights, the young ratings took on the might of British naval authorities and almost succeeded, but for the lack of support from their national leaders. There were many firsts recorded over those four tension-filled days. For the first time, the blood of men in uniform and civilians was spilled in a common cause. The death toll in the clashes was the highest recorded until then, almost all restricted to the city of Bombay. After four brave but bloody days, the ratings, as advised by Congress leaders like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, surrendered. Bombay and the naval ships and establishments slowly limped back to normalcy. A significant chapter in the history of the Indian freedom struggle had come to a sad end.

The fire of revolt at Talwar was ignited by the Commanding Officer Arthur Frederick King, a foul-mouthed racist, a man with a ‘big body but small brain’, who faced the wrath of the ratings for the offensive manner in which he treated them. In retaliation, a group of ratings had deflated the tyres of his car and painted a ‘Quit India’ slogan on its bonnet. Incensed, he confronted the men under his command, shouting: “You sons of coolies, sons of bitches.” The ratings, most aged between 15 and 24 years, decided that enough was enough. On February 17th, they refused dinner and, early the next day, struck work. When the morning bugle was sounded, not a single rating turned up. The mutiny, uprising, revolt, whatever name historians would give it, had begun.

The next four days saw hunger strikes, ominous threats from both sides, hijacking of naval vessels, capture of 22 ships around the Bombay harbour by the ratings who lowered and removed the British Ensign from each ship and shore establishment and replaced it with flags of the Congress, Muslim League and the Communist Party. So serious was the uprising that the four-inch guns fitted on these ships were pointed at the Gateway of India, the Yacht Club and the Taj Mahal Hotel, with threats to blow them up if any harm was to come to the striking ratings. The British cut water and electricity supply to the barracks, warned the strikers of dire consequences, and even threatened destruction of the Royal Indian Navy. Seven hours of gun battles ensued, along with low-level flights of bomber aircraft over the harbour and frantic calls to warships outside Bombay to crush the mutiny.

For four days and nights, the young ratings took on the might of British naval authorities and almost succeeded, but for the lack of support from their national leaders. There were many firsts recorded over those four tension-filled days

To express sympathy with the ratings, and instigated and encouraged by the call given by the Communist Party, thousands of residents of Bombay poured out onto the streets in protest, demanding justice for the young sailors. Some extreme elements looted European establishments, post offices, banks, and damaged motor vehicles and railway stations. British Tommies and police were ordered to shoot at sight. In two days of public protests, close to 400 were killed and almost 1,500 injured. The flurry of events and movements, once the news of the mutiny broke, revealed the panic and consternation within the top brass at General Headquarters in Delhi. By evening of the first day, February 18th, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, the commander-in-chief of the Indian Army, was informed. He relayed the news to Viceroy Lord Wavell. The aircraft carrying Flag Officer Commanding Royal Indian Navy (FOCRIN) Admiral JH Godfrey to Udaipur had barely touched down when he was met at the airport with an urgent, confidential message about the mutiny. He immediately flew to Delhi and a day later took a special flight to Bombay. With extreme trepidation, the news was conveyed to Westminster after studying the situation closely for an entire day. Panic was visible everywhere.

While the root cause of the naval mutiny lay in the inhuman living conditions, injustice and torture these ratings were forced to endure along with appalling food, the inspiration came not from India-based political leaders but the INA led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The INA was held in great esteem, a force that inspired patriotism greater than that by the Indians serving in the army under the British. Gandhi himself admitted, albeit grudgingly: ‘The hypnotism of the INA has cast its spell upon us. Netaji’s name is one to conjure with. His patriotism is second to none…’ (‘How to Canalize Hatred’, Harijan, February 23rd, 1946).

Gandhi publicly opposed the strike in keeping with his commitment to a non-violent struggle, but the developments posed a peculiar challenge for the three main political parties who took divergent positions in relation to the uprising. The communists, expectedly, were open and aggressive in their support, inciting students, trade unions and ordinary citizens to revolt, calling on the ratings to avoid surrender. Senior Congress leaders, in touch with British authorities and privy to insider information on British reaction, advised patience and a peaceful resolution, even making leaders of the naval strike promises they were in no position to fulfil. Many were also eyeing Cabinet berths in a post-independence government. Young socialists of the Congress, impatient with the tardy pace of the freedom struggle, were ready to shun non-violence but lacked the political clout to override party stalwarts. The Muslim League, meanwhile, had a single agenda—to nurture their Muslim constituency and the creation of Pakistan. In this political flux, only one thing was clear: No one wanted to rock the boat of freedom.

There was only one leader who stood up for what she believed in—Aruna Asaf Ali, the sole dissenter against the conspiracy of silence by the country’s prominent leaders

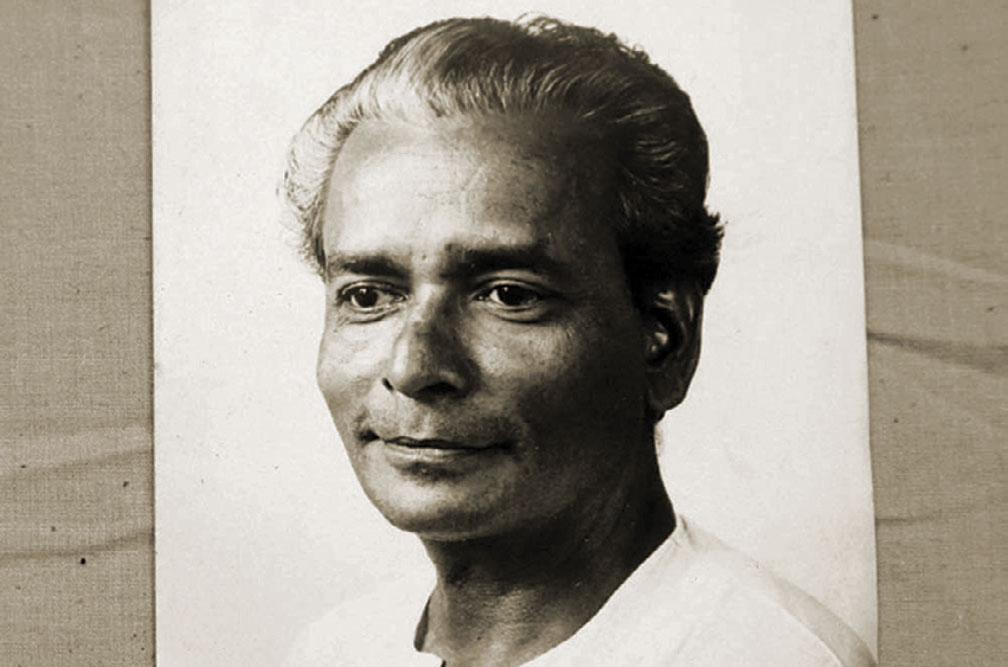

Amidst all this, there was only one leader who displayed the gumption to stand up for what she believed in—Aruna Asaf Ali (née Ganguly), the firebrand socialist and the sole dissenter against the conspiracy of silence by the country’s prominent leaders. A leading figure in Congress, she was famously remembered for her underground activities during the Quit India movement in 1942. Most notably, for hoisting the Congress flag at the Gowalia Tank Maidan in Bombay on August 9th. A friend of Jayaprakash Narayan, Ram Manohar Lohia and other socialists, she was ideologically closer to Jawaharlal Nehru than to Sardar Patel. Married to Asaf Ali, a prominent member of the Central Legislative Assembly, for her, attaining independence took precedence over the method. A day after the Quit India movement was announced by Congress, many major leaders were arrested. Aruna went underground and did not come out of hiding until the end of 1945. When she did, she engaged with the naval ratings and activists from the Ex-Services association and others who were involved in the planning for the ratings going on strike. She was a friend and mentor of Kusum and PN Nair, in whose Marine Drive flat meetings related to the uprising were held and planned. She knew exactly when the strike would begin. In fact, it had been announced by the striking ratings that she would address them at HMIS Talwar on the day the strike began. Though the reasons were never made clear, she did not show up that day. Her no-show had left the ratings hugely disappointed.

However, she had already made her stand clear, saying the demands of the ratings were “entirely legitimate” and asked political parties like Congress to “extend their moral support”. Other Congress heavyweights clearly did not share her views. For prominent Congress leaders, it was the timing of the mutiny that had upset their political calculations. Several of them, like Nehru, Gandhi and Patel had been focused on a smooth transfer of power. Freedom, they believed, should not have to be wrested from the British by a bloody confrontation. Strong action by British defence forces would inevitably delay the process. In his book, Revisiting Talwar, Dilip Kumar Das writes: ‘The Congress leaders had been in touch with the British authorities in Delhi and Bombay since the beginning of the strike. While they had conveyed their disapproval of the strike, in public their stance till 21st was neutral and one of non intervention. The Governor of Bombay was kept abreast of various steps Congress was taking to neutralise the situation.’

The dilemma for most political leaders was that national sentiment was rapidly rising in favour of the ratings who had rebelled, and they realised it would not benefit them politically to go against the tide. On one level, they were in solidarity with the spirit of the movement. While the strike was ongoing, Maulana Azad, then Congress president, issued a statement saying: ‘India is not in a mood to tolerate any action that may even have the semblance of the suppression of the national spirit in any quarters,’ while adding: ‘The unexpected RIN strike has led to a sequel which has assumed distressing proportion…I am in contact with the authorities and I am seeking a prompt and practical termination of the strike.’

Mahatma Gandhi, by sheer coincidence, had arrived in Bombay from Wardha by the Calcutta Mail on February 18th, the day the mutiny began. Sardar Patel received him. The Times of India Bombay edition reported: ‘A huge gathering was present in the compound of Rungta House where Mr Gandhi said his prayer. Though Gandhiji may not have been fully apprised of the naval disturbance that day in HMIS Talwar he did refer to recent disturbance and violence in Calcutta and Bombay.’ He asked the people not to ‘divert from the path of peace. What was the good of throwing stones at the British? …Freedom can only be achieved through truth and non-violence…’ Gandhi had a packed schedule on February 18th and 19th when he met many prominent local Congressmen. Sardar Patel was with him practically the entire time he was in Bombay. The two could not have failed to discuss the developing disturbance. Gandhi left for Poona on the evening of February 19th without commenting further on the naval uprising.

Once the confrontation between the British establishment and the Indian sailors intensified, Indian political leaders soft-pedalled the issue. It was clear that Congress leaders, while condemning the violence, also did not want to be seen as being disassociated from the movement. On February 19th, Sardar Patel issued a statement. He had been in consultation with the governor of Bombay, John Colville, and with Asaf Ali in Delhi who had been in close touch with Auchinleck. He advised the naval ratings to be patient and peaceful and urged citizens to maintain strict discipline. The Congress, he said, was working towards a “peaceful settlement”.

For the first time, the blood of men in uniform and civilians was spilled in a common cause. The death toll was the highest recorded until then, almost all restricted to Bombay

The same day, DS Vaidya, secretary of the Bombay Committee of the Communist Party, issued a leaflet which said: ‘Yesterday 5,000 men in the Indian Navy went on strike. Among them are Hindus, Muslims, Christians, men from all provinces…speaking all languages. They all stand united…We appeal to the leaders of all political parties in Bombay to support these demands.’ Gangadhar Adhikari, too, issued a call to the citizens of Bombay, students and transport and mill workers on February 21st, supporting the uprising and a complete hartal on February 22nd. The party newspaper he edited, the People’s Age, was critical of Patel, Nehru and Gandhi in an editorial: ‘He [Patel] shed tears over those who died and condemn [sic] “hooliganism”. But he had, however, no single word to say in condemnation of the British military “hooliganism” who had fired indiscriminately and killed hundreds of innocent lives.’ The editorial added: ‘Gandhi ji said that the Hindu Muslim unity achieved in joint violence at the barricades must lead to mutual violence…in saying so he deprecates the glorious Hindu-Muslim unity in resisting the police and the military repression…the fact is that Congress leaders are not thinking in terms of joint struggles and not even in terms of struggle.’ On Nehru, he commented: ‘To say that a slave people shall never take to arms because its guns are not as big as those of the handful of oppressors, would not be a counsel of wisdom but of cowardice.’

Sensing that the situation was heating up, Aruna travelled to Poona the next day, February 20th, and met Gandhi. It was a longish meeting lasting almost two hours. Meanwhile, Congress continued to blame the communists for fanning the flames while saying they were “urging naval authorities to redress just grievances of the naval ratings” and pressing for an early resolution of the crisis. By now, the Muslim League had made its position clear. Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, general secretary of the All-India Muslim League, had a long discussion with Auchinleck who assured him that there would be no victimisation of the Muslim men involved in the strike. The Nawabzada asked Muslims to “follow the advice of Quaid-e-Azam Jinnah and help restore normal conditions.” He went on to state: “[Mr Jinnah] has already assured the RIN men that he will do his best to see that their legitimate grievances are redressed…Quaid-e Azam has made an appeal to the Muslims in particular not to create any trouble and not to play into the hands of those who want to exploit the situation for their own ends.” Jinnah did not really equate the RIN uprising with the struggle for freedom.

With tension escalating, Aruna Asaf Ali sent a telegram to Nehru on February 21st. It said: ‘Naval strike, tense, situation serious, climaxing to close…Request your immediate presence in Bombay.’ The telegram angered Sardar Patel, who wrote to Gandhi expressing shock that she had persuaded Nehru to come to Bombay to meet the sailors as only he could lead them and avert the tragedy. He wrote: ‘This she [Aruna] did as she could not find my support. Jawahar wired me asking if his presence was necessary…I advised him not to come. Yet he is reaching here…Well! Let him. But the fact that he comes here on account of Aruna’s telegram is sorrowful indeed!’ Nehru had taken the first train to Bombay but was persuaded by Patel not to meet the striking ratings. He returned to Allahabad the same day. This possibly started the beginning of the collapse of the uprising.

The political divide over the naval ratings’ uprising was proving advantageous to the British. For them, there was little difference between the non-violent Gandhian approach and the movement to create a mutiny

On the same day, Aruna also issued a statement offering her services as a peacemaker. In a special message to the ratings, she said: “The strike of the Indian naval ratings is now four days old…Vice Admiral Godfrey broadcast seems to threaten further bloodshed…This should remove any later pleading by the Admiral that force was used as there was a danger to public peace.” On February 22nd, all major newspapers gave prominent coverage to an appeal by the Communist Party as well as the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC) to carry on the struggle. In response to this, Sardar Patel issued a statement asking naval ratings to lay down their arms and surrender. Congress President Maulana Azad also pressed for calling off the strike. However, in an interview to a newspaper after the surrender, he admitted: “It is quite obvious from the facts we have been reported that Indian ratings of the RIN went on strike as the result of what they considered was gratuitous insult to national self-respect.”

In a press conference called on February 22nd, Aruna Asaf Ali said: “Only the unconditional withdrawal of military patrols and the immediate lifting of bans on civil liberties fulfil the formality of surrender and bring normal conditions in the city of Bombay.” Referring to the seven-hour gun battle at Castle Barracks, she added: “It was a welcome sign that Indian people had plucked up enough courage to face bullets from machine guns…there was a time when our people shuddered at lathi blows but those days were of the past.”

Later that day, members of the strike committee, led by MS Khan, met Sardar Patel who asked them to surrender unconditionally. It was widely believed that the British authorities had assured Patel that if he persuaded the ratings to surrender unconditionally, he could assure them that there would be no victimisation. When Khan asked him to give this in writing, Patel lost his temper. Dilip Kumar Das writes in Revisiting Talwar: ‘The worthy Sardar flew into rage and thumping the table said “when you don’t trust my words, how can you trust my writing…I assure you on behalf of Congress that not a single one of you will be victimized”.’ Finally, on February 23rd, Khan, head of the NCSC, made the announcement: ‘In the present unfortunate circumstances…the advice of the Congress to the RIN Ratings is to lay down arms…After discussion with Sadar Patel who had assured them that Congress would see that there was absolutely no victimization and confident that the Congress and Muslim League would stand by their word, they surrendered “to the people of India”.’ In a press release aimed at their countrymen, the NCSC said: ‘…Our strike has been a historic event in the life of our nation. For the first time the blood of men in the services and in the streets flowed together in a common cause.’ The statement ended with ‘Long Live Our Great People. Jai Hind’. It was an anticlimactic end to the first serious armed threat to British rule, but was also a ‘mutiny of the innocent’ as termed by BC Dutt, the prime mover of the uprising.

The political divisions were still evident, with Aruna Asaf Ali publicly disagreeing with Gandhi, saying she was unable to understand him calling upon the ratings to resign if their condition was humiliating: “If they did that, they will have to give up their only means of livelihood. Moreover, they were fighting for principles…it simply does not lie in the mouth of Congressmen who were themselves going to the legislatures to ask the ratings to give up their jobs…Gandhi ji further says that the rulers have declared their intention to quit in favour of Indian rule. This statement is not borne out of facts. The way of renunciation is the way of the sanyasi and not of the Bren gun and the bullet. I do not think therefore that Gandhi ji is justified in his belief. The people are no more interested in ethics of violence and non-violence. They just want to resist repression. They are no more cowards…they have adopted a certain amount of recklessness in their resistance. They are dying but do not complain…”

The first sign of the impending uprising came, appropriately enough, at the HMIS Talwar, a signal school for naval ratings in Colaba. A strategically important naval establishment, Talwar became the platform for the launch of the mutiny

For his part, it was clear that the country’s tallest leader, Mahatma Gandhi, would not compromise on his crusade of non-violence. On February 23rd, after getting news of firing by British troops in Bombay and the resultant killings of almost 400 civilians, he issued an appeal to stop the “thoughtless orgy of violence”, adding: “Let it not be said that India of the Congress spoke to the world of winning Swaraj through non-violent actions and belied her word in action and that too at the critical period of her life.” He added: “I have followed the events now with painful interest…in as much as a single person is compelled to shout “Jai Hind” or any popular slogan; a nail is driven into the coffin of Swaraj in terms of the millions of India…Looting and burning of tram cars, insulting and injuring Europeans is not non-violence of the Congress type much less mine…what I see happening now is not thoughtful. Why should they [naval ratings on strike] continue to serve if service is humiliating for them or India?”

In reference to the ratings, Gandhi said, “In resorting to mutiny they were badly advised. If it was for grievances, fancied or real, they should have waited for the guidance and intervention of political leaders of their choice…if they mutinied for freedom of India, they were doubly wrong…They were thoughtless and ignorant if they believed that by their might they would deliver India from foreign domination.” On February 26th, he issued another statement advising that India should bank upon the arrival of the Cabinet Mission in March. “Nothing will be lost by waiting…it betrays want of foresight to disbelieve British declaration and precipitate a quarrel…is the official deputation coming to deceive a great Nation? It is neither manly nor womanly to think so.”

Gandhi’s views also brought into the public gaze his differences with Aruna Asaf Ali when he said: “People were very much interested in knowing the way which would give freedom to the masses. Aruna and her comrades have to ask themselves whether the non-violent way had or had not raised India from her slumber of ages and created in them a yearning…I congratulate her on her courageous refutation of my statement on the happening in Bombay. Except for the fact that she represents not only herself but also a large number of underground workers, I would not have noticed her refutation, if only because she is a daughter of mine—not less so because not born to me or because she is a rebel…I admired her bravery, her resourcefulness and burning love for the country. But my admiration stopped there…Aruna would rather unite Hindus and Muslims at the barricade than on the constitutional front…Fighters do not always live at the barricades. They are too wise to commit suicide. The barricade life has always to be followed by the constitutional. I appeal to Aruna and her friends to make wise use of the power their bravery and sacrifice has given them.”

The day after the surrender, on February 24th, Aruna felt the need to clear the air about her involvement and disagreement with other Congress stalwarts. She issued a public statement which said: “There has been considerable speculation about my part in origin of RIN strike…On 17 February ratings of the RIN apprised me of the tension in the navy and their grievances…They called upon me to intervene on their behalf and to address a meeting… I also gave an account to Sardar Patel. The situation was very grave as the navy held out a threat of bombardment within twelve hours. I was therefore compelled to wire Pandit Nehru to come and save the situation.”

By this time, the political divide that had been created over the naval ratings’ uprising was proving advantageous to the British in terms of their crackdown on the strike and its leaders. Commander-in-Chief Auchinleck issued a statement where he spoke out against politics in the armed forces, clearly referring to the uprising: “It matters not what form collective disobedience takes—whether negative—such as refusal to work or refusal to eat—or positive such as demonstrations, mark an act of violence. The milder forms of insubordination are infectious and can easily lead to violence.” For the British there was little difference between the non-violent Gandhian approach and the movement to create a mutiny of sorts.

While the root cause of the mutiny lay in the inhuman living conditions, injustice and torture, the inspiration came not from India-based political leaders but the INA led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The INA was held in great esteem, a force that inspired patriotism greater than that by Indians serving in the army under the British

WHATEVER THE METHOD and motive of political reaction to the naval strike, in terms of public opinion and sympathy, the communists had scored over the Muslim League and Congress. Realising this, Congress gave a call for a public meeting on February 26th at 6PM on the sands of Chowpatty beach. Nehru had cancelled his election tour of Bihar and the United Provinces and arrived in Bombay on February 25th. A huge crowd was waiting for him at the Victoria Terminus. Instead, on the advice of Sardar Patel, who had sent a special messenger to meet him en route, he alighted at Byculla station. Authoritative accounts of the time say that Patel spoke in strong words to Nehru and advised him against the folly of helping the rioters. Nehru persuaded himself to be converted to Patel’s point of view. According to Kanji Dwarkadas, in his book Ten Years of Freedom, ‘From Byculla he [Nehru] drove straight to Sardar Patel’s residence in Marine Drive…He was briefed on the tense situation in Bombay by Sardar. Before addressing the public meeting, Pandit Nehru met members of the media. At the press conference, he admitted that there was great sympathy for the naval ratings in the city but condemned the violence instigated by Communists. Referring to exchange of gunfire in Castle Barracks, he said a great deal of excitement had been caused by the firing of guns which made people think that a pitched battle was being fought in Bombay Harbour. “When there is excitement it is very easy to put spark to that excitement.”’ He also had meetings with groups of naval ratings (who had rebelled), naval officers and politicians. One such delegation, as mentioned in Admiral Satyindra Singh’s book Under Two Ensigns, met Pandit Nehru at his sister Krishna Hutheesing’s residence. The group consisted of Commander SG Karmakar (later Rear Admiral) who had taken over as commanding officer of Talwar the evening before the mutiny, his businessman friend Venkatrao Ogale, politicians Rao Saheb Patwardhan and his brother Janardan Patwardhan, Appa Pant and Lieutenant SN Kohli (later chief of the independent Indian Navy). In the book, Kohli is quoted as saying: ‘When we went in, Panditji said: “What can I do for you?” I was taken aback because I thought he had sent for us… I piped up: “At no point has the Congress given the Armed forces clear guidelines or a clear directive how to conduct themselves in the present politically disturbed condition of the country.’’ Panditji went red in the face and retorted, “Thank you for teaching me my job.”’ They had to quickly change the discussion to the origins of the mutiny.

Nehru would expand on his views during the public meeting at Chowpatty, which was presided over by Patel. The subject of the public meeting was to be ‘The Tragedy from which the City has just emerged.’ A mammoth rally of over two lakh people, Patel started the proceedings by taking a swipe at the communists and asking the gathering not to be misled by “those who attempt to exploit the anti-imperialist feelings and political awakening of the masses and direct them into wrong channels. I ask the people of India not to listen to those who calling themselves Congressmen are determined to create anarchy and disorder…if you think the Congress leadership is wrong it is up to you to replace the Congress leadership.” He condemned the steps taken by the ratings calling it “nothing but hooliganism”. He reiterated, “Ship of freedom was coming close to the shore of India, people should not go out and sink it.”

Nehru was more forthcoming when he declared at the meeting: “If politics meant the love of freedom, I am 100 per cent with politics in the army. Our armed forces have every right to revolt against the foreign ruler…The conflict that has been going on is to find a way out to serve their country in a fitting manner rather than remain as mere tools of a foreign government to repress their own countrymen or work as an army of occupation for India. They are lost between their duty to their country and their soldierly discipline…So far the armed forces have been freely used as instruments of repression by our foreign rulers…The present RIN strike was one of a series of demonstrations of vehement protest against the humiliation and discrimination between the whites and Indians.” He concluded: “The “Janata” and the soldier have come together and realised that they both have one common aim—the freeing of their county from foreign yoke.” He also publicly admitted that Sardar Patel and Maulana Azad had given a guarantee that there would not be any victimisation. He said neither Patel nor Maulana Azad was now in a position to keep that guarantee in the present state of slavery. This was the first admission of Congress going back on its word barely five days after the ratings had been persuaded to surrender by giving those exact guarantees.

It was an anticlimactic end to the first serious armed threat to British rule, but was also a ‘mutiny of the innocent’ as termed by BC Dutt, the prime mover of the uprising

In Delhi, political leaders led by Asaf Ali and Sarat Chandra Bose, called for a special sitting of the Central Assembly. During the debate, Minoo Masani of Congress, declared: “The grievances which have been simmering for a long time have now blown up as a result of the offensive behaviour of Commander King and arrest of two of the naval ratings comrades…Our conception of discipline is different because the contrast is between Indian and British conceptions. That is because we do not accept the moral basis of your authority [pointing to War Secretary Philip Mason]. Your law is not law to us because it has not got the sanction of the people of this country behind it; and when your military or civil law is broken, every one of us instinctively reacts with sympathy for the rebel. In other words, real cause of this mutiny is the existence of British rule in this country…Sir, my friend will say: “Oh, we want to go.” I can then only say that you have lingered so long that you are bringing our edifice down in ruins…I make an appeal to you to go while there is still an army, a navy and an air force in this country intact. And sooner you go the better for this country…If these boys indulged in unwise actions, Vice Admiral Godfrey also indulged in action that smack of extreme irresponsibility…I hope sir, now that the lesson has been learnt, it will result in the redress of the legitimate grievances of these men and a recognition of their patriotism and of the self respect that they have preserved for this country.” Equally intense debates had taken place in the British parliament, but with both Conservatives and ruling Labour on the same side, a rare sight generally visible in times of war.

As for the ratings, they were trapped between two sets of rulers, each with their own ambitions. One gradually preparing to leave India and to do so in a peaceful manner without the blot of a mutiny to stain their departure, and the other sensing imminent power and anxious to avoid any signs of lack of discipline in the armed forces they would preside over. What hurt the ratings most was the sense of abandonment by the political leaders, including Gandhi. As one rating put it: ‘We were trained for combat with guns. It was not possible for us to fight through a charkha.’ They felt deeply disappointed and betrayed: ‘Despite all the assurances of Sardar Patel and Pandit Nehru we were subjected to all sorts of atrocities…We suffered quietly in the hope…But our hopes have been belied, our faith shattered…Our only fault was that we loved our motherland and exhibited to the rest of the country that we too were with them in their struggle for freedom.

The ratings were trapped between two sets of rulers, each with their own ambitions. One gradually preparing to leave India and the other anxious to avoid any signs of lack of discipline in the armed forces they would preside over

If patriotism is a crime, we surely are guilty.’ Biswanath Bose, in his book RIN Mutiny: 1946, revealed that he wrote a letter to Nehru, then prime minister, which said: ‘My name was included as a leader and I was subsequently punished with dismissal and imprisonment…Since my release I have been trying to contact you unsuccessfully for reappointment in the Naval services…If there is any law for those who have been dismissed for taking part in the freedom movement of the country that they cannot enter into their respective services then I must ask you to explain why yourself being a leader of Congress, a political party, should have the post of a Prime Minister!’

The tragic epilogue to the mutiny of 1946 was that the ratings who had participated in the revolt would be sent home with a third-class one-way ticket and their salary dues docked for even the slightest damage to their uniforms or kit. They were sent home with the warning: Do not enter Bombay again.

(This article draws on Pramod Kapoor’s forthcoming book 1946: Naval Uprising that Shook the Empire | Roli Books)

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba