The Earthspinner

A HORSE WAS IN FLAMES. It roamed beneath the ocean breathing fire and when it shook its mane the flames coloured the waves red and when it erupted from the water it was as tall as a tree and the fire made the crackling sound of paper. It towered above the low-roofed house Elango lived in. The flames were at the hooves, the long solid cannons, and as they reached the muzzle, he worried that the horse would burst from the heat. Had he remembered to leave an outlet? Anxiety forced its way through his troubled sleep and all at once his eyes were open.

He lay still, elbow propping his head, dazed by his dream, needing no clock to tell him it was just three in the morning – the hour of wakefulness for petty thieves and born worriers. He shut his eyes again to see better his burning horse and understand what it could mean. By dawn the hens would start their clucking and crowing and his brother's wife would resume her daylong monologues with them, cooing at them to come and get grain, coaxing them to lay more eggs. The time until then was short, it was his own, and he wanted to stay suspended in his dream, clinging to its fading threads.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

He got down to work on the horse that very morning. In singlet and shorts he tramped through Kummarapet to the scrubland a short distance from their house, down to the pond from where he dredged clay for his pots and idols. When this wasteland too had been given over to a landlord, his pond and its surrounding soil would be gone and with it his clay – he knew this as the future. His grandfather had worked with the earth from here and dimly in his memory his great-grandfather before that. His grandfather had told him when he was a child why the neighbourhood was named Kummarapet: because of their ancestors, the potters – the kummara – whose village it used to be. If you cut me open you will see clay in my veins, his grandfather used to say. From earth to earth was for him an inheritance. But their thriving workshop was long gone and there was only Elango at the pond now, though most of the clay he needed had to come by truck from a supplier. It cost money, and he could not raid it to make his horse for fear of his older brother noticing.

Often Elango thought that if – as people liked to say – god was a potter, then He had spun him and his brother to life on different wheels, from different earth. "No problem, no problem" was Vasu's favourite expression. Not for nothing was he a tout at the magistrate's office forever devising ways for people to dodge property surveys, fudge application forms, forge documents and jump queues. If there was a rule, he knew how to find a way around it. His eyes would gleam, he would scratch his oiled scalp with his pen and say, "Just relax, Sir. You have a problem, I have the solution."

Where Vasu was a walking calculating machine, Elango hardly bothered to add two with three, and the earthen lamps he made, the gods and goddesses, the humdrum things like water pitchers, curd pots, flower pots and tea glasses that he sold in stacks to wholesalers – these wouldn't have taken him very far. His main source of income was Sudhakar, an old college-mate who now designed the interiors for a chain of hotels. He ordered terracotta urns from Elango for the gardens and lobbies of the hotels. It was he who had pulled off a place for him at the national exhibition in Delhi, and enthusiastically promoted Elango's pots at hotel exhibitions. When the two of them sat and smoked together over a rum and water, Sudhakar would say he wanted the world to know great artists here lived in poverty and yet made extraordinary things. "Somewhere in the muck there has to be a lotus growing," they would chorus. It was something one of their college teachers, Mr Murthy, was given to repeating as he ran his eyes despairingly over the class full of boys he called loafers and rascals, and even as they grinned at their shared memories, Elango was sometimes surprised by his friend's spontaneous affection. His own quieter sense of Sudhakar being the brother Vasu never was made him feel a little guilty.

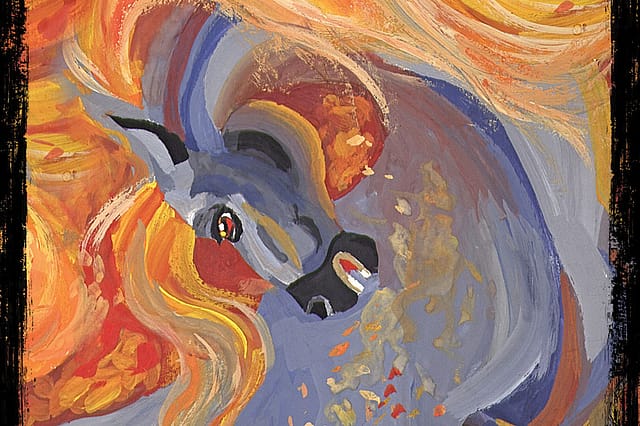

Elango's urns were monumental enough, and timeless, but the terracotta horse came from a past more ancient, a place deep inside him where memories and stories lay waiting like a rich seam of clay. In his dream the horse had risen on its own like an earthen fountain. It wore a necklace of beads and its ears were like two mango leaves on either side of its magnificent head. On its forehead there was a design that he couldn't yet clearly see. On its back was a tassled saddle which led to a tail that flew like a flag. The mane swept down the neck in an earthen wave, the eyes stared straight ahead, gazing at eternity. Elango knew his own horse would not satisfy him if it did not match this dream animal.

He hunched over the bed of the pond with his spade and crowbar and began to dig. The mud was green with slime in places. Closer home was a smaller pond on which waste floated like a slow-moving patchwork sheet. But where he was digging now like his forefathers, was the potters' pond, a store of earth from which gods had been made always, and superstition threw a wall around it that no bricks could. It was clean and it drew birds and insects. When the sky over it had a few clouds and a soft breeze bent the rushes on its banks, it was as if it had been there since the earth began and the same bone-white egrets had picked their way around it even then.

Today there was not a cloud in the flat blue sky. October, but you would think it summer. It was hard, hot work and his singlet was soaked with sweat, but he felt energy and hope coursing through him. His dream had meant something. The horse was both sign and envoy, telling him Zohra would be his, but he would have to work to make that happen.

For how long had he lived with Zohra in his head? He could not be sure any more because it felt as if it had always been so. She and her grandfather had probably moved into the neighbourhood at the end of the last winter, almost a year ago. Elango had not noticed her at first though he must have seen her around Moti Block, the scabby grey tenements above the shops, where she and her grandfather lived. That whole year now felt like lost time: crazy not to have stored away those glimpses for sustenance.

Imprinted in his mind was the day the turmoil in him began. It was at the weekly street market when she stopped at his stall. Their hands had touched when reaching out for the same lamp.

"It's very pretty," she said.

"When you light it, it will cast the shadow of a flower," he said.

"Really? A rose or a hibiscus?" she asked him in an innocent voice. Even as he was wondering if she was making fun of him, she had picked up another pot, removed its lid. She raised her eyes to him questioningly. Brown, he noted, their rims filled with kajal.

"It's for setting curd," he said. "The best curd – there will be no water swilling around."

"The best curd because it's the best pot with the best lid?" She looked up at him with a mischievous smile, and then quickly down again.

After that she had said something about the dolls too, he had no recollection what. The impish smile had been fatal. He knew he wanted to listen to that voice, see her smile for hours, days, years, his whole life.

The next week she had come back – why? What was he to her? She had come again not to buy a pitcher but because she had felt something stir inside her too – he wanted to believe this, and by degrees it grew into a certainty in his mind. He tried to make sense of the way everything shifted that day for Zohra, as if a stage had been swept clean, the curtain raised, for her to occupy the centre.

She was in sunset yellow and the gauzy pink dupatta that trailed over her shoulders. There was a tiny blue pendant at her neck.

"The lamp which makes the shadow of a flower when . . ."

"Yes, yes, there it is," Elango said. He wanted to give it to her. He wanted to give her all he had on the table. She could have anything, she had only to ask.

She reached across the table for the lamp and her dupatta slipped down to the crook of her elbows. He caught a glimpse of deep shadows between curves in the moment it took for her to right her clothes, and this she did promptly, with a swift apologetic look at him. He noticed the patch of sweat that darkened the yellow fabric at her armpits, the narrow wrists, the cleft chin, the leathery mark on her right arm that must be from a burn. As she walked away, he saw her hips moved oddly because of a limp. Something about that limp undid him. He felt himself sucked dizzily into a spiral of longing and lust from which he knew he would not free himself.

One waiting customer, a woman with a gold nose stud poking into each nostril said, "Is anyone going to tell me the price or do I need to be eighteen again?"

He hardly heard her although he answered her with practised ease. "Four rupees, Amma, but for you, because it's the best evening of the year, it is two only."

There was nothing he could do that day other than steal glances at Zohra as she made her way among other stalls down the street lined on both sides with peddlers shouting themselves hoarse about the superior quality of their clothes, toys, kites, food. There were two others with clay goods and people were bargaining so hard he could not leave his stall for a moment to slide away after her. And if he did follow her would he ever return? He dragged himself back to the business of earning. But from the next evening he took to visiting the Moti Block shops for a smoke if he saw she was there buying rice, millets, sugar, oil. To stand next to her for a few minutes, pretending not to notice her, even as he directed every atom of mental energy inside him to make her stay where she was – a little longer, five minutes more. Three minutes. He could not gather the courage to nod at her, or find a word to say. When he chanced upon his reflection in shiny car windows he did not like the face that looked back at him. Why would she?

Zohra did not come back to him with a single gesture that would have given him hope. He began to think he had misread her. Or that, like him, she had lined up the facts of their lives, turned them over carefully, seen the intractable problems, then quelled her feelings for him. She had

succeeded where he had not.

(This is an excerpt from award-winning author Anuradha Roy's forthcoming novel The Earthspinner, to be published by Hachette in September 2021)