Surprise Gains

BILL CLINTON'S VISIT TO INDIA IN MARCH 2000, not long after the Kargil War ended in late July 1999, included an address to Parliament where he noted that while he had not come to South Asia to mediate on Kashmir, there was a need for restraint and respect for the Line of Control (LoC). He prefaced the observation by noting the role of American diplomacy in "urging" Pakistan to return to its side of LoC—referring to the famous dressing down Clinton gave to then Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on July 4, making it clear that a Pakistani withdrawal could not be linked to a US diplomatic intervention on Kashmir. While Clinton's extraordinary intervention, recorded in detail by his advisor Bruce Riedel, was a significant moment, it would not have come about if Indian forces were not actually winning the conflict. Should things have played out differently, then Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee might well have received advice on the merits of negotiation with Pakistan. After the war was over, then US Foreign Secretary Madeleine Albright said, "[Y]ou did not put a foot wrong [during the Kargil crisis]." The trick bit lay in the Vajpayee government's decision, despite costs of fighting an uphill battle to oust Pakistani intruders, not to expand the theatre of combat beyond the Himalayas. This act of forbearance helped isolate Pakistan internationally and won India support across the world.

IRONICALLY ENOUGH, SOON AFTER THE WAR ended, Sharif was ousted by Pakistan's army chief General Pervez Musharraf, the man responsible for the failed Kargil adventure. 9/11, Musharraf, the US and Afghanistan are another story, but before that an important recalibration happened in US-India relations. Clinton's visit, and his remark that by "listening to each other, we can build a true partnership of mutual respect and common endeavour", marked the correction of a historical pro-Pakistan tilt in US foreign policy. This was the same US president who had come down on India like a tonne of bricks after the 1998 Pokhran II nuclear tests. The end of the Cold War, along with some bold political and economic decisions, helped India break free of the straitjacket of power-bloc politics. A diminished Russia remained an ally and friend while India rapidly developed its ties with the US, critical for gaining expertise in high-tech, space, agriculture, counter-terrorrism and, not the least, access to top-end military hardware. The resolution of the Soviet threat meant the US was not overly bothered about India retaining its strategic ties with Moscow. After all, this was a heady moment, the birth of a uniquely unipolar world. Russia's assertive behaviour under Vladimir Putin began to change some of these assumptions, but not too much. Putin's decision to use air power to aid his Syrian ally Bashar al-Assad (the Russian leader once asked Barack Obama to provide the coordinates for bombing Islamic State targets) was a warning of sorts, which was largely ignored. But the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February this year changed everything. It blew away the post Cold War order for good and brought war to the heart of Europe again. Russia in alliance with China posed a new menace for American interests not seen since the heyday of the Axis powers.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

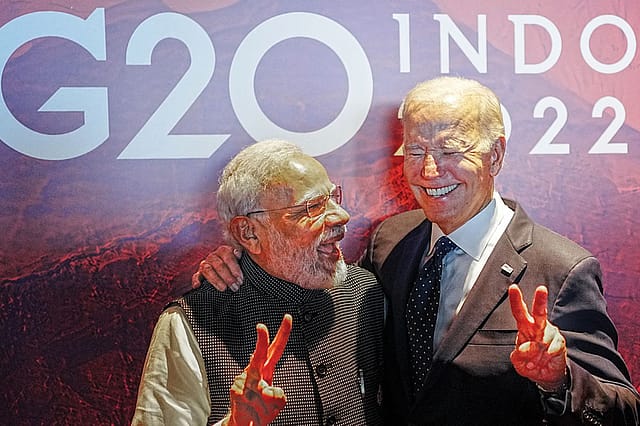

Getting around CAATSA (Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act) against the import of missile systems from Russia was one thing, but riding the backwash of the West's anger about Putin's war was another. There was genuine outrage at the violation of Ukraine's sovereignty and an expectation that India would do the "right thing" and condemn Moscow in no uncertain terms. The choice was not easy given that India could not support a blatant breach of the United Nation's norms and Ukraine's borders. The demands that India join the US and Europe in the sanctions being imposed on Russia were echoed by a vocal domestic opinion, including a section that has criticised the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for alleged erosion of democratic benchmarks. Apart from the curious case of expecting a government they have criticised as "authoritarian" behaving contrary to its grain, there was a trap in the arguments offered. If India did succumb to calls to act against Russia, it would end up losing an important counter-balance to China at a time when the border faceoff was unresolved. Pushing Moscow closer to Beijing and losing a partner, even an increasingly whimsical one, made little sense. All the more so when India's military continues to depend on Russian wares and the Ukraine conflict began to jack up energy prices. A miffed Biden administration expressed its disappointment but the pushback from External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar was sharp: India would do what it could to secure its energy supplies while calling for the combatants to negotiate an end to the war. There was also a clear articulation—underlined by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Putin—that war was not an acceptable option. It took some time but the perceived ambiguity in India's position, that it was running with the hare and hunting with the hounds, was resolved with the G20 leaders' statement in Bali in November accepting the Indian formulation on the Ukraine war and the unacceptability of any talk of nuclear weapons. Things turned a complete circle with the US acknowledging Modi's role in bringing about an important consensus with Russia and China on board.

The 'no limits' alliance between Russia and China made public to the world in February, ahead of the Winter Olympics, poses a serious long-term challenge to India. The unstated third extension of this formation is Pakistan, China's partner in containing and destabilising India. Retaining and deepening its ties with Russia are a strategic necessity for India for a host of reasons that include access to the Arctic and the minerals of Siberia. In the months that followed the June 2020 Galwan clash between Chinese and Indian troops, the bilateral relationship has been contested and testy. The two sides have maintained a process of military and diplomatic communication that resulted in disengagement in areas where China had encroached on the Line of Actual Control (LAC), but Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping did not move beyond handshakes when they met at multilateral forums. In recent weeks, China has objected to joint Indian and US military exercises in Uttarakhand while a crippling cyber attack on the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi was reportedly traced to Chinese hackers. India's assumption of the G20 presidency and Modi's unambiguous intent to use the opportunity to leverage tourism, culture and business could not have been missed by Beijing. The view of several delegates at the first meeting of G20 sherpas in Udaipur that India may be uniquely positioned to talk to both sides of the Ukraine divide—and that it can also be a bridge between the global south and the developed world—is hardly to China's liking. And certainly not at a time when massive protests against the zero-Covid policy spoilt Xi's party just weeks after successfully choreographing a third term and placing his cronies in key Communist Party positions. With comparable population sizes, India's success in controlling Covid and reviving its economy provides a sharp contrast to the discontent in China. The fresh physical brawl in the Tawang sector in Arunachal Pradesh, while being primarily a result of overlapping claim lines, may also indicate that the frequency of such faceoffs could increase through 2023 during India's G20 presidency.

As global commodity prices cool somewhat, even as shortages and price rise take a very heavy toll on many African and Asian countries, and inflation moderates, India can be said to have navigated a tough year with more than a passing grade. The stupendous success of BJP and Modi in the Gujarat elections, and a strong performance despite losing in the Himachal Pradesh Assembly and the Delhi municipal polls, is evidence that inflation and issues of unemployment raised by some commentators and political opponents have not resulted in voter anger against the ruling dispensation. The China challenge and the bitter fallout of the Ukraine war will tinge the dawn of the new year, but Indian diplomacy will feel that 2022 has ended with more gains than could have been anticipated.