Steady In the Storm

How Modi is navigating a rough diplomatic terrain after the Russian invasion of Ukraine

/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/CS1.jpg)

The world was surprised by a new toughness in India’s response following the clashes between Indian and Chinese troops in Ladakh in the summer of 2020. Chinese expectations of an easy Indian capitulation did not materialise. Almost two years later, and more than two months after Russia invaded Ukraine, the world—the West in particular—is coming to terms with a fait accompli New Delhi has given it. The message: India knows how to balance its national interests against its international responsibilities. It will not be lectured on either. Delhi’s countering of China and taking an independent stand on the war in Ukraine have reinforced each other. It is the result of a firmness of resolve that marks a break with the past

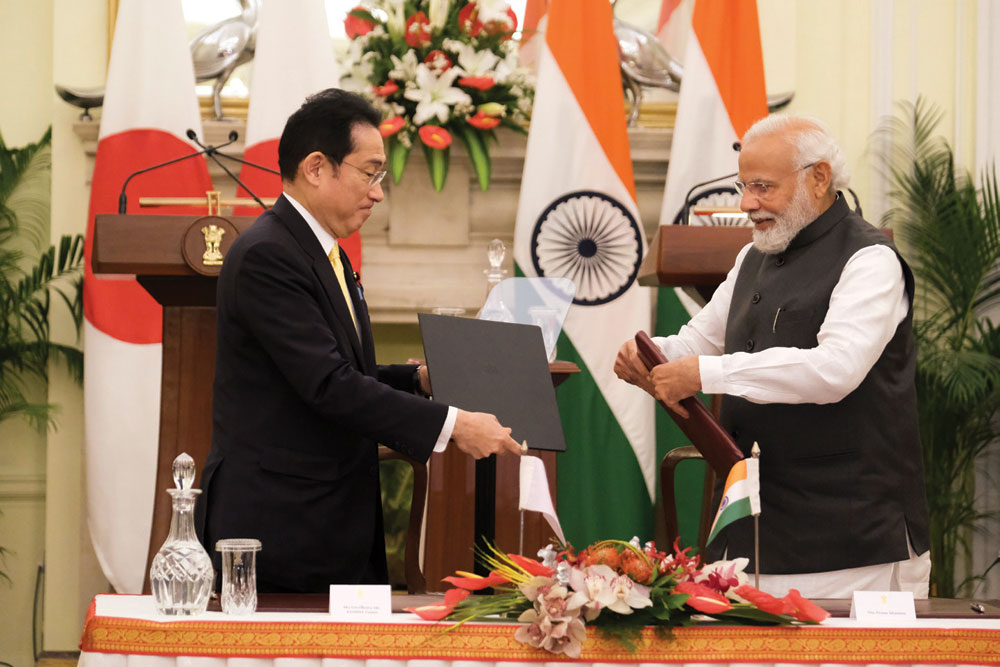

WHEN BRITISH PRIME MINISTER BORIS JOHNSON ARRIVED IN INDIA recently, seeking to pressure New Delhi to change its stand on the Russia-Ukraine war was likely to have been the last thing on his mind, irrespective of public expectations in Europe. He had just visited Kyiv and promised arms supplies to his beleaguered host Volodymyr Zelensky. But on his two-day India visit, Johnson gushed instead about the free trade agreement (FTA) between India and the UK, stressed economic and strategic ties, and spoke of getting attention like an Amitabh Bachchan or a Sachin Tendulkar. Leaving no scope for any misinterpretation, he insisted on calling Prime Minister Narendra Modi his “khas dost”, or special friend.

At a press briefing after his official talks, Johnson hummed and hawed in reply to a direct question on whether he had tried to impress upon Modi the need to change India’s perceived “pro-Russia” stand, and few of those present were surprised. No one missed the tightrope walk on “uhh, everyone knows India’s historic relations with Russia,’’ and “err, after Bucha, India came out strongly against war crimes….” Delhi had clearly stuck to its guns and refused to budge under pressure from the West. A stream of dignitaries had tried this before Johnson, after all, with little success despite subtle bullying, even taking recourse to naming and shaming tactics about India being “on the wrong side of history,” (that is, not falling in line with the US-led NATO and allies).

In India, the reaction of the so-called liberal ‘intelligentsia’ to the Modi government’s stand on Ukraine-Russia had strong shades of déjà vu, much like their response to the Centre’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. Columns of fear-mongering reports based on speculative mathematical models projecting millions dying were flaunted two years ago. For Modi’s critics, weaponising the virus and the so-called projections was imperative to achieving what they had failed to do politically: pinning down the prime minister and his government on a substantial issue.

When the war between Russia and Ukraine broke out, the same set smelled a fresh opportunity. There was anticipation that Modi would finally be caught between a rock and a hard place, between the sanctions-threatening pressures of the US and the tried and tested relationship with Russia. A hard choice between a supplier of most of India’s defence needs and a new provider of advanced weapons. In the end, it was surmised, Modi would be forced to take the ‘moral’ position of unequivocally siding with the US-led NATO, abandoning the ‘fence-sitting’ position that put India, according to the pulpit thumpers, very shamefully “on the wrong side of history” alongside North Korea, the UAE, Pakistan, China and other states. It appeared to matter little to the commentators that some 45 poor African nations, heavily food-and-aid-dependent on the two warring countries, also abstained or stood with Russia in the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) vote later.

Just as in the case of Covid, wherein lives and livelihoods were both at stake and it was imperative to balance the two delicately. But such concerns were dissed at the altar of anti-Modi political gains and little concern spared for key issues, such as India’s diplomatic dilemma and its need to protect its national interests. That much of India’s angst arose not only from its traditional ties with Russia and dependence on Moscow in delivering high-value armaments like missile systems and fighters but also because of harsh geostrategic realities that make the country vulnerable to an aggressive China was conveniently brushed aside. The idea was to tarnish Modi and undercut his popular appeal. But to the horror of many critics, Modi managed to balance his equations with the US and the West on the one hand and his line with Russian President Vladimir Putin on the other. In doing so, he firmly prioritised India’s national interests, refusing to fall into the trap set by ideological adversaries. While refusing to vote against Russia at the UN, the Modi government still sent humanitarian aid to Kyiv and Ukraine’s neighbours and quite directly asked Putin to not insist on settling his country’s security concerns, however legitimate, through war and territorial aggression. Instead, India urged for talks to resolve all issues.

HOW EXACTLY DID India manage this balancing act in international diplomacy? Thus far, in the context of the Ukraine-Russia conflict, India has navigated international diplomacy to protect its national and geostrategic interests even while steadfastly standing on the side of peaceful negotiations and an immediate end to hostilities. Delhi continues to demonstrate its sovereignty and independence in decision-making, so much so that it drew praise from former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan who lamented that the US was behind a plot to unseat him. This, despite finger-wagging visiting US diplomats asserting that an enfeebled Russia would not come to India’s aid if China encroached on its territory again. The argument was more recently amplified by former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. But the threat has lost its bite. India has figured out what it needs to do with aggression on its northern borders and it is for the West to work out its response. The West has used this stick to try and beat India, implying a sanctions-weakened Russia would depend heavily on China and find itself unable to bear down on Beijing. Russia dismissed this, however, pointing out it would be able to have relations with both Delhi and Beijing inasmuch as India does with Washington and Moscow. Some vocal Western geostrategic commentators have even maintained that a fully sanctioned and economically weakened Russia would end up as Beijing’s vassal.

Apart from the subtle diplomacy that our career diplomats are engaged in and the nuanced resolutions Delhi adopted at the UN, India’s actions are a reflection of its key concerns on China threatening its territory. Post-Bucha, where Russia was allegedly involved in mass killings of civilians, India has been strident in its condemnation, calling for an independent probe. India’s help to Ukraine signalled not only acknowledgement of imports of fertiliser and commodities but a ‘thank you’ in facilitating the extraction of Indian students caught up in the war.

Much of the credit for India’s steering of its very distinct path and protecting its interests in the region while dealing with a stormy international terrain goes to Modi. He showed resolve and clarity in achieving the objectives Delhi had set for itself. Earlier governments could well have done the same but ran the risk of being awed by towering personalities and the power of the so-called liberal opinion as reflected in the columns of big Western news publications. There was, besides, the Nehruvian legacy of the fear of ostracism by the West and Delhi being reduced to a caricature in the powerful capitals of Europe and the US. In his distinctive manner, Modi recast non-alignment—often just a political catchphrase in the past—as a clearheaded pursuit of national interest.

On his two-day India visit, Boris Johnson talked about the FTA between India and the UK, stressed economic and strategic ties. Leaving no scope for misinterpretation, he insisted on calling Narendra Modi his ‘khas dost’

When Jawaharlal Nehru indulged the Soviet Union’s aggression in Hungary in 1956 and Indira Gandhi played from the same rule book in 1968 in Czechoslovakia and again, after 1979, in Afghanistan, India was not that visible on the global stage. Delhi was largely consigned to the Third World and almost seen, in the case of Afghanistan, as a satellite of the Soviet Union, pretensions to non-alignment notwithstanding. But India has come a long way since. Today, in keeping with Zbigniew Brzezinski’s reading in 1997 (in his book The Grand Chessboard), India is a big geostrategic player on the Eurasian and global stages. It has signed up to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), is a permanent invitee at the G-7, part of the G-20 grouping—a table Delhi once only dreamt of sitting at but had remained elusive for long.

Modi’s firmly holding a distinct position on the Ukraine-Russia conflict is a major embarrassment to the US since India stood out as the one democracy supposedly in the ‘opposite camp’, puncturing its aggressive ‘democracies vs autocracies’ narrative. The Biden administration, at least in the initial days of the Russian invasion, used every platform to imply that India’s many abstentions on votes against Russia at the UN and its buying of oil at a discount were camouflaged support for Moscow. Modi saw it differently. On the issue of energy security, for instance, he was categorical that Indians have to be assured of energy supplies. How firmly India held on to its perceived non-aligned position—insisting that its decisions on the energy front were those of a sovereign nation prioritising the interests of its own people—was clearly apparent when External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, in a rock-star performance at the 2+2 talks with the Biden administration, pointed out that the discounted oil that Delhi bought from Russia was significantly less than what NATO nations purchased from Russia in a single evening, and that it constituted just 2 per cent of India’s needs. He also categorically asserted, under pressure to take clear sides on the Ukraine issue, that India had chosen “the side of peace”. More recently, at the Raisina Dialogue 2022, he was asked “How does India, as the world’s largest democracy, deal with Russia’s attack on Ukrainian democracy?” Jaishankar replied, sotto voce, “The idea that others define us, that you know somewhere we need to get approval, I think, that’s an area we need to put behind [us].”

The considered stand by the Modi government has resulted in a situation where India continues to import oil from Russia and the latter will make good on components of the S-400 missile system, to be paid for in rupee-rouble exchange terms. At the same time, India now continues with its position in the Quad (including Japan, the US and Australia) to counter China on the trade and non-military fronts (albeit not being part of AUKUS). Its member nations have reaffirmed their faith in India, asserting that Delhi is crucial for the fight they perceive as poised between democracies on the one hand and a concert of autocracies on the other.

When there is that level of conviction from the head of government, courage can be seen down the pecking order. The three Cs—conviction, courage and clarity—were often missing in previous governments. Modi’s decisiveness has been compared by some with that of Hungary’s Viktor Orbán who was recently re-elected. Hungary has, among all EU nations, firmly refused to sanction Russian energy purchases, prioritising its people and energy security. When Zelensky asked Hungary to choose a side, Orbán announced, “Hungary has chosen. Hungary is on Hungary’s side,” and rode back to power.

Within the Quad, it was India that first took the bold step of announcing bans on Chinese Apps. Australia has yet to respond to China flexing its muscles in its own backyard. In the Quad, both Japan and Australia know India can stand up to China like never before

THE SQUEAMISHNESS EXHIBITED by previous Indian governments on the global stage resulted in weak and half-hearted responses, generating a bundle of contradictions that led to Delhi being ridiculed. Take, for instance, the case of Pakistan in earlier years. India was happy with its ties with Islamabad even if Pakistan sent terrorists by night and played cricket by day. As a result, after every terror attack, India would issue statements that maintained that all issues would be negotiated. Meanwhile, cultural and sporting engagements continued.

The clarity of approach exhibited by Modi reflected in earlier audacious responses to regional security threats, whether the surgical strikes after the Uri attack or airstrikes on Balakot in Pakistan. These took place despite the unsolicited chorus of advice as to why Islamabad needed to be engaged. However, it is now proven that not only has India not lost in any way in the decisions it took but it also successfully upped the ante by following up on Uri and Balakot with the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir, scrapping its special status. It thus integrated the border state fully with itself, to the chagrin of Islamabad, and slammed the door on a possible international intervention sought by Pakistan based on the region’s ‘special status’. In the longer term, this has fully aided India in asserting on the global stage that any intervention on Kashmir at the behest of Pakistan or others will not be entertained by Delhi—and that there is nothing to offer Pakistan on this front in any talks. This move, unlike in the past, did not meet any major opposition or condemnation from the big global powers, in itself evidence of the heft India has acquired of late. Such firmness on Kashmir and Article 370 was lacking under previous regimes which were regularly swayed by vocal liberal opinions within the country and without. For many years, a statement from a prominent US Senator or a mid-level State Department official on Kashmir was enough to unsettle Delhi. Today, India stands on its own side and does so unapologetically.

Thanks to the 3C strategy, India has successfully overcome its self-imposed fetters. The result is evident also in the case of China next door that has become increasingly threatening in recent years. Beijing based its 2020 aggression on the responses of past governments in Delhi to its creeping acquisitions. It leveraged Delhi’s continued eagerness to pussyfoot around critical issues along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) and its choosing to separate trade from territorial issues, relying on an undefined border to shroud its faint-heartedness in a cloak of considered strategy. The premise, loosely spelt out, resembled that of Thomas L Friedman’s Golden Arches theory—that no two countries with McDonald’s franchises have gone to war with each other. In short, once India cooperated with China to boost common trade ties, mutual economic gains would naturally lead to stronger and peaceful ties in other spheres, acting as a disincentive against any misadventure.

US threats that worked earlier no longer do so. Jaishankar iterated it yet again when he said, ‘We engage with the world on the basis of who we are rather than try and please the world by being a pale imitation of what they are’

BUT MODI TOOK the stand that it would not be business-as-usual with regard to Beijing’s incursions into Indian territory. Banning Chinese apps and threatening to downgrade trade have resulted directly in not just bilateral trade being based on better acknowledgement of Delhi’s stand but Beijing has also been forced to the table to negotiate the withdrawal of troops to earlier positions. Relations between Beijing and Delhi, both nuclear powers, soured two years ago after clashes in Ladakh. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s recent visit to Delhi was the first high-level official trip since then, one that elicited much interest given the unspoken agenda. The visit, the first in the wake of the Ukraine-Russia war, saw Delhi telling Beijing off on raising Kashmir at international forums. This included blocking India’s membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), helping Islamabad end Masood Azhar’s designation as a global terrorist and, most crucially, making it clear that India would no longer be a passive victim of China’s territorial encroachment.

India, while clearly preferring talks to bring peace and end the conflict, has accepted that Russia has committed aggression on Ukrainian territory wrongly instead of finding other means to redress its grievances. But equally, its pushback against the US threat of sanctions for oil purchases from Russia, even when there are fissures among the EU ranks on continued energy purchases by Germany, Hungary and other countries (also seeking a waiver for Italy’s fashion goods that have a market in Russia), has exposed the double standards of the West. This, when the West expects India and far poorer African and troubled West Asian nations to view the world through the Ukraine prism, to the direct disadvantage of their own peoples. Over and above all it is India’s acute awareness that while the US says Russia will not come to its aid if China turns aggressor again, there is neither any surety of the West moving beyond lip service. Even within the Quad, it was the Modi government that first took the bold step of announcing bans on hundreds of Chinese apps. Australia, meanwhile, has yet to respond to China flexing its muscles in March in its own backyard. A proposed security treaty between China and the tiny chain of islands in the Pacific, the Solomon Islands, could potentially allow China to establish its first naval base in the region, rebuffing Australia, the core of the AUKUS alliance in the region.

Delhi’s staunch refusal to be part of any sanctions on Russia other than what was mandated by the UN has also proved to be the right decision, given clear indications now that Russia and Putin have not been deterred to the extent that NATO had expected. Russia’s continuing aggression in Ukraine, despite sanctions, has also failed to help Zelensky in any significant manner. What is important is that, if Delhi had not stood its ground, it would have clearly hurt its own interests on multiple counts, including energy security, defence purchases and territorial integrity in the face of Chinese incursions.

India is the largest democracy in the world, the second most populous market and a nuclear power. Today, it has the potential to rapidly transform from an emerging nation to the ranks of developed countries. India’s naval presence in the Indian Ocean provides a big leverage in the region, something the West is well aware of. The Indian Army’s strength was demonstrated in 2020—several months since the Galwan clashes—in the area between Black Top and Thakung Heights on the Pangong Tso’s south bank, when it surprised the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) by occupying the heights. In the Quad, both Japan and Australia know India can stand up to China like never before. Fear is no longer dressed up as considered strategy against Beijing.

Despite pressure from liberal lobbies, both the US and other Western countries are now completely comfortable in dealing with Modi and are compelled by a multiplicity of reasons to strengthen ties. The latest evidence of that is the stream of ministers and diplomats from the US, Japan, the EU and Australia seeking to convince India to turn away from Russia but also looking for bilateral benefits. Apart from offending the leftwing in the Democratic Party, US President Joe Biden, too, is aware of the need to keep India on his side. Not the least of the reasons for such change of heart, on both Modi and India, is the fact that the threats and the disparaging tone that worked earlier no longer do so. Jaishankar amplified it yet again this week when he said, “We engage with the world on the basis of who we are rather than try and please the world by being a pale imitation of what they are.”

India’s geography is unchanged, its armed forces are manned by the same officer stock (although capabilities have improved drastically) and the diplomatic corps are also as before. But the shackles India imposed on itself have vanished under Modi.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba