Shiv Sena’s Last Stand

Uddhav Thackeray turned the party genteel but in the process deprived it of the aggression that fuelled its growth. The price of his chief ministership is being hostage to old family friend Sharad Pawar

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

|

22 Nov, 2019

|

22 Nov, 2019

/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Shivsena1.jpg)

Aaditya (left) and Uddhav Thackeray (Photo Imaging: Rohit Chawla)

To understand how easily Uddhav Thackeray and Sharad Pawar embraced each other after the Assembly elections, it would do well to remember a story from the 1960s. Bal Thackeray, the Shiv Sena’s founder, had plans to launch a Marathi news weekly and had a partner in the venture: Pawar. After the planning and logistics were done in Thackeray’s home, when a launch date had to be decided, they turned to Thackeray’s sister who had a reputation for divining the future. She went ‘into a trance’ and prophesised that not only would the magazine be a success but do so well that not a single copy would remain unsold. Recounting the incident in his autobiography On My Terms: From the Grassroots to the Corridors of Power, Pawar writes, ‘She was right. There was no trace of the magazine in the market as there were no takers. Soon, we had to wind up the joint venture.’ The collaboration might have bombed but the Pawar-Thackeray relationship would endure till the latter’s death.

In the decades to come, Thackeray would mock Pawar in his speeches, sometimes terming him a ‘sack of flour’ for his obesity. But Pawar fondly reminisces in his book, ‘In private meetings, however, Balasaheb was a warm person who stood by his friends through thick and thin… In September 2006, Supriya was elected for the first time to the Rajya Sabha from Maharashtra. Soon after her candidature was announced by the NCP [Nationalist Congress Party], Balasaheb called me up to offer his party’s support. ‘Sharadbabu, I have seen her since she was a knee-high girl. This is a big step in her career. My party will make sure that she goes to the Rajya Sabha unopposed.’ I was deeply touched by the gesture. However, the Sena was in alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Maharashtra. ‘But what about the BJP?’ I asked. Balasaheb’s reply was instant and true to his character. ‘Oh, don’t worry about Kamalabai [kamal or lotus being the BJP’s party symbol). She will do what I say.’

And so, when Devendra Fadnavis found the rug pulled from under his feet as he got ready for a second term as Maharashtra chief minister, chances are long before the election, Uddhav, Thackeray’s son and now the chief of the Shiv Sena, and old family friend Pawar, who leads the NCP, had already decided the contours of how the game would be played. It was fortuitous for them that the perfect numbers came up—the BJP couldn’t form a government without either the Sena, NCP or Congress.

The association—often political, always personal—with Pawar was just one in the vast personal network of Bal Thackeray. It stretched from Congress prime ministers to socialists to the top BJP leadership. The story of how numerous chief ministers in Maharashtra used him thinking of the Sena as a tool all the while strengthening it is well known. But Thackeray once even allied with the Muslim League. Uddhav’s network meanwhile is almost non-existent outside Maharashtra and even in the state, as recent events have demonstrated, he had few friends in the BJP, an ally of three decades. All of his eggs are now in the basket of Pawar but for a weakened party, its vigour now only a memory, that might not be an altogether bad thing. The Sena, for all that it represented, adulated and reviled for decades, had never been confused until the advent of Uddhav. Without direction, being in power is probably the only way it can hope for a future.

Uddhav has neither the oratory nor the political genius of his father. He is a lonely and embattled figure getting by on legacy. But the BJP wrote him off as irrelevant and that was a mistake

Even by the standards of politicians who spend their lives creating their own myths, Narayan Rane’s telling of his life in the book No Holds Barred: My Years In Politics is so self-serving that every event in it is a movie in which there is one wronged superhero—Rane himself—while the villains keep changing according to the political calamities that trailed him after a brief nine-month spell as chief minister in 1999. Thackeray giving him the post had been unexpected for many but not for Rane himself. He had for years been assiduously angling for the position, cultivating his leader. Until he became chief minister, Rane was considered important but only as the muscle of the party, something he himself concedes. His eventual falling out with the Sena was a combination of the party losing power in Maharashtra, Thackeray’s increasing reliance on Uddhav to take over from him and Rane’s recognition of his own abilities to be an independent player wanted by other parties. There is however one portion in his book in which Rane still has an astute analysis of why the Shiv Sena faces an existential crisis.

He terms the party having a ‘clear lack of sense of self and identity’. And this he attributes, with unexpected recourse to psychology, to the personality of Uddhav and his position in the Thackeray household; of the three brothers—one would pass away in a car accident and the other became estranged—Uddhav is the most mild-mannered and soft spoken. Rane writes, ‘In an attempt to stand apart from his two aggressive brothers and a towering Raj [Thackeray], Uddhavji adopted an intellectual, gentlemanly persona. When Saheb made him the undisputed heir, Uddhavji set out to change the Sena’s style of functioning to suit his own acquired demeanour.

Although this sounds great in theory, it doesn’t work in practice.’ Far from a virtue, being genteel, according to Rane, is diametrically opposite to what the party’s own disposition is, the one that made it such a potent force in Maharashtra. So long as it was unapologetically beholden to antipathy, it sped along. To Rane, as someone who was part of the Sena’s rise in Mumbai, the ‘politics of hate’ is a necessary condition. As he writes, ‘The problem—in my opinion, and there are many who will agree with me—is that the Sena has always played the politics of hate and believed in the ideology of ‘thokshahi’. It is well known that Saheb had a strict no non-violence policy! Any political historian will tell you that the Sena was born as an anti-establishment body; that it first incited the Marathi manoos against immigrants, then Hindus against minorities by propagating the idea of a Hindu Rashtra. When it was in opposition in Maharashtra, it loved to hate the government of the day. Then in 2014, when it allied with the BJP to form the state government, it realized that it didn’t have any more issues. So, owing to its lack of a solid political ideology, it began to play hate politics against its own ally and its own government! This was inevitable as the Sena has historically believed that it can continue to retain its political base only if it succeeds in keeping the common man on edge.’

This is as far as the dazzle of Rane’s insight goes. His anticipated fall of Uddhav, as recent events demonstrate, was off the mark while he himself remains in the wilderness. Also, the ‘politics of hate’ is not a magic ingredient. It has a limited shelf life and needs to be calibrated carefully. Bal Thackeray used the card twice—first against south Indians which sent the Shiv Sena rocketing into Mumbai’s political sphere after its founding in the 1960s and then in the 1980s, he used it against Muslims. But once the Sena got to power in the mid-1990s, then it was just boring mainstream politics—more noise than action. Rane’s prescription would, in fact, be tried by Thackeray’s nephew Raj after he set up his breakaway Maharashtra Navnirman Sena and began a campaign against north Indians. After a few headlines, it fizzled out. The Maharashtra of the new millennium was nothing like the 1960s or 1980s. Possibly Uddhav recognised it but that is still only half the job. There needs to be an alternative to replace the outdated ideology.

Rane’s own life story is a testament to who were attracted to the Shiv Sena. His impoverished family had left him behind in Mumbai and returned to their village. He was a rough character in a rough neighborhood until, enthralled by Thackeray’s speeches against ‘outsiders’, he became part of the rank and file, rose to be a shakha pramukh, then a corporator when the Sena captured the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) and through the exhibition of manic loyalty, organisational prowess and disdain for the law became part of the inner circle of Thackeray. A fortuitous set of circumstances propelled him to the highest position the party could offer. When the gangster Arun Gawli started his own party, his retort to those who questioned his ambition was that if Rane could become chief minister, why not him? The answer: he didn’t have the Sena to give him political legitimacy. The difference between protection rackets run by gangsters and politicians is the difference between crime and society.

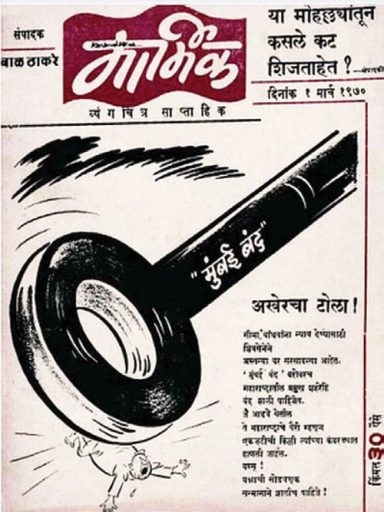

Bal Thackeray gave guidelines in Marmik for how Maharashtrians must act. It shows the parochiality of his political imagination. For instance, Maharashtrians were asked to employ only Maharashtrians

IN THE 1960s when Thackeray launched the Shiv Sena, he had a fertile soil of Maharashtrian discontent to sculpt from. When his satirical magazine Marmik first highlighted this dormant volcano of grievance, the magnitude of the response led to Thackeray venturing into active politics even though in the beginning his stated end was to not get into politics. In 1980, sociologist Dipankar Gupta analysed in a paper in the Sociological Bulletin titled ‘The Appeal of Nativism’ the growth of the Shiv Sena through articles that appeared in Marmik in which Thackeray did things like putting up lists of non-Maharastrian employees in government offices and alleging that employment exchanges had been corrupted to be biased against locals. Gupta wrote, ‘This two-way affair, the encouragement from the readers to the incitement of Thackeray kept building up till it convinced Thackeray in May 1966 that an organization called the Shiv Sena should be formed to look after the interests of Marathi speaking people in Bombay.’

On July 19th, 1966, Thackeray gave guidelines in Marmik for how Maharashtrians must act and it shows the parochialityof his political imagination. There were 11 points in it. Maharashtrians were asked to employ only Maharashtrians. Maharashtrian shopkeepers to only buy wares from Maharashtrian wholesalers (and also be courteous to customers). Maharashtrians to not sell property to non-Maharashtrians and if they heard of any such deal to report it to the Shiv Sena office. They were asked to shrug off lethargy and form housing cooperatives. They were told to boycott Udupi hotels and not purchase anything from non-Maharashtrian shopkeepers. If any Mahashtrian got into trouble, other Maharashtrians should help them. Youths were encouraged to learn English and stenotyping. ‘These guide lines were embodied in the oath that the Shiv Sainiks had to take in the early years of the movement. (The practice was given up in 1967),’ writes Gupta. If you take the Sena today, there is no insistence on even a single point.

Thackeray turned out to be a spectacular organiser, dividing the city into units and divisions where the shakha (local office) would be ubiquitous. He encouraged aggression and would later go on to term it as ‘constructive violence’, something fomented through his speeches from inception itself. The Sena’s annual Dussehra rally at Shivaji Maidan began the year the organisation was launched. The first one was on October 30th, 1966, and it filled the Maidan to the brim. In Bal Thackeray and the Rise of Shiv Sena, Vaibhav Purandare writes on the aftermath that day, ‘After Thackeray’s first speech, the crowd that had shown up for the rally attacked Udipi restaurants as it dispersed, immediately marrying the new organisation’s image with its mascot, a growling tiger. Dilip Ghatpande, one of Thackeray’s earliest associates, says: ‘The boys’ blood had started boiling after listening to Balasaheb’s speech. On the way to Dadar station, there was an adda (den) of South Indians where illegal activities like matka (gambling) took place. The angry youth stormed the place.’… Four lakh people had gathered for the Sena’s inaugural rally, and the response to Thackeray’s appeal was such that the Marmik editor was himself left a little bewildered. The rally overnight established the Shiv Sena as a force to reckon with in Mumbai. The city got a Tiger, and the state a new slogan: Jai Maharashtra.’

As the Shiv Sena’s following increased, becoming a political party was the natural consequence for them. By the mid-1980s, they had won the municipal corporation and tapped enormous sources of funding. A decade later, on the back of post-Babri Masjid demolition riots in which the Sena participated openly, they came to power in the state. It was a government that overpromised and underdelivered, like four million free houses for slumdwellers, schemes that ended up becoming money-making enterprises. Mellowed down by power, having established that they could be as corrupt as the parties that preceded them, the party’s disconnect with reality was evident when they announced elections six months ahead of their term’s end and were voted out. It would take 15 years for a return to power but by then they had been relegated to junior partners by a BJP riding the Narendra Modi wave.

It was Bal Thackeray’s age that caught up with the Sena, built entirely on his charisma. As he became more withdrawn because of his health, his anointment of Uddhav was resisted by Raj

Ultimately, it was Bal Thackeray’s age that caught up with the Sena. The party was built entirely on his charisma and as he became more withdrawn because of health reasons, his anointment of Uddhav was resisted by people like Rane and Raj Thackeray who broke away taking men and resources. Also, the rank and file were now clueless as to what they stood for. Purandare writes in his book, ‘Uddhav’s leadership was beginning to court controversy too. In 2002-03, he floated a campaign called ‘Mee Mumbaikar’ (I am a Mumbaikar) in an attempt to bring North Indians, by then a sizeable vote bank in Mumbai, into the Sena fold. This alienated the Sena’s traditional mass base and was called ill-defined even by those who were clear that a pluralistic outlook was the only way to do politics in India.’

In Mumbai, at least, the Sena still remains umbilically connected to the people. In Maximum City, Suketu Mehta has a description of a shakha as a microgovernment. He writes, ‘The Shiv Sena Shakha in Jogeshwari was a long hall filled with pictures of Bal Thackeray and his late wife, a bust of Shivaji, and pictures of a muscle-building competition. Every evening, Bhikhu Kamath, the shakhapramukh, sat behind a table and listened to a line of supplicants, holding a sort of durbar. There was a handicapped man come to look for work as a typist. Another man wanted an electric connection to his slum. Husbands and wives who were quarreling came to him for mediation. An ambulance was parked outside, part of a network of several hundred Sena ambulances ready to transport people from the slums to hospitals at all hours, at nominal charges.’ Despite all its evolutions, this picture of the local shakha has remained unchanged for decades, the reason the Sena survives despite the absence of Bal Thackeray. But it is adrift, like a vehicle running on its reserve fuel with no gas station in sight. Uddhav has neither the oratory nor the political genius of his father. He is a lonely and embattled figure getting by on legacy. But the BJP wrote him off as irrelevant and that was a mistake. It might have been where the relationship was headed but the Sena is still a force in the present.

Uddhav’s outwitting of the BJP comes with a flip side. His party is now entirely hostage to Pawar. They have to rely on him to negotiate with the Congress. Pawar will decide what will happen in the BMC, now that without BJP support the Sena is in a minority there. Will Uddhav be chief minister for all of five years, as some reports suggest? Will he have to share it with the NCP? Will the NCP and Congress carve out all the money-making ministries such as revenue, public works and education? The Sena has little leverage in any of this. That is the price for Uddhav’s chief ministership. To get back his independence, he will need to pitch the BJP against the NCP but it will then be against the guile of Pawar. For the Shiv Sena to grow, even such a balancing act might not be enough.The only way it can remain relevant is by vote share. Unless he does something extraordinary as chief minister, the Shiv Sena might only have bought itself a few years more.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande