Resisting the Robotic

Holding on to the power of movement

Tishani Doshi

Tishani Doshi

Tishani Doshi

|

13 Aug, 2021

Tishani Doshi

|

13 Aug, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Robotic1.jpg)

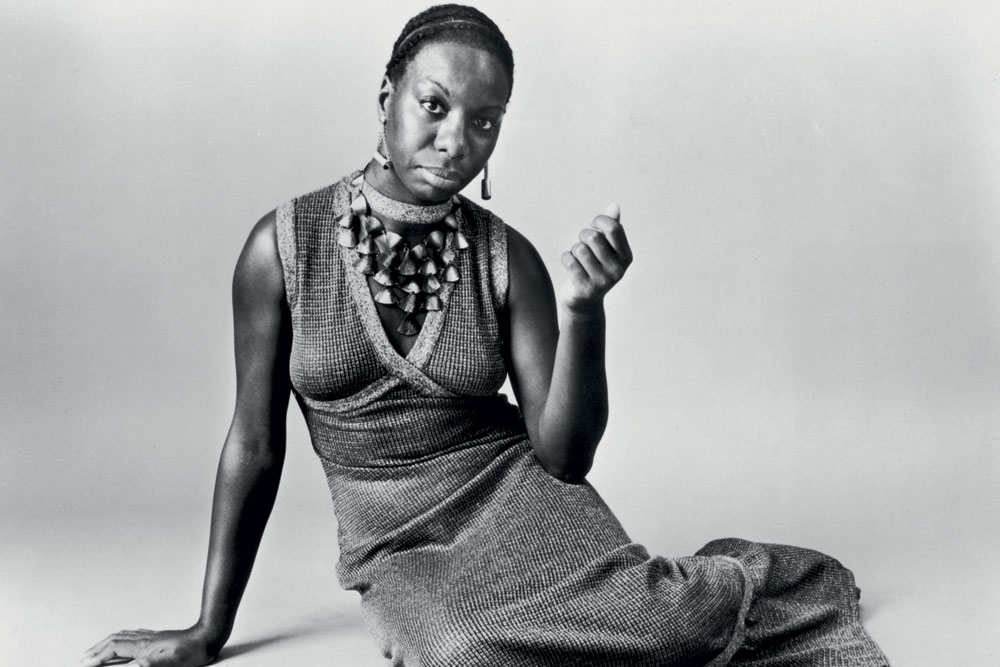

Pina Bausch’s choreography, Café Müller (Photo: Alamy)

IN 1969, WHEN NINA Simone, then 36, was asked what freedom meant to her, she said, “What’s free to me? Same thing it is to you, you tell me!” And then she laughs, shaking her head. “It’s just a feeling. It’s just a feeling. It’s like how do you tell somebody how it feels to be in love?… I’ve had a couple of times on stage when I really felt free, and that’s something else,” Simone gets increasingly animated, circling around this mythic quality. “I’ll tell you what freedom is to me. No fear! I mean really, no fear… Lots of children have no fear… that’s the only way I can describe it.” The interviewer tries to push on, but Simone talks over him, wants to sit in her epiphany for a while. “A new way of seeing,” she whispers.

It’s strange that childhood is always evoked as a time of freedom in our lives, because legally, it’s when we are least free. Children belong to their families and can only emancipate themselves after they become adults, unless you’re Britney Spears, in which case—never. The systems that have been set up to protect children in most countries have routinely failed them by placing minors in the homes of sexual predators, refusing to acknowledge abuse in schools and religious institutions, and perpetuating complicated custody laws, which deny children any right of say. Still, the myth of the halcyon childhood persists. Even kids who have it hard, like the orphans in Dickens’ novels, can push through and prevail if their imaginations are prairies of untouchable sacred space, suggesting that if we protect this inner private life, we can all, no matter how insignificant, assert some level of free will.

As a child, I was terrified. I worried that my parents would die in an accident. I was afraid of shadows on the bedroom walls, of ghosts and tree spirits, of a giant tidal wave sweeping all humanity away. And yet, it was a time of peak freedom. I occupied my body in a way I’ve never been able to since. My body was a vehicle for bum-skating on soapy bathroom floors, of bike-riding and scraped toenails, of climbing trees and pretending to be an Olympic gymnast, of dancing naked and joyous in the thrill of my body, my being. It’s hard to know when that sense of freedom began to be chipped away. I remember the maid gossiping about how the upstairs neighbour boy regularly spied on me through the window grills, and from then on, it was cover up, close your legs, shut the door. Shame entered. These memories, unreliable as they are, form the bedrock for our adult narratives. I think of childhood as one long season where boundaries and time are limitless and your inner compass is a whirligig. It’s why we are so often disappointed when we try to re-enter scenes of our childhood—the houses and playgrounds, only to find them shabby, reduced, when at the time, they’d felt like a queendom.

In the late 10th century the Kashmiri polymath and philosopher Abhinavagupta gave us the radical idea that it is in the power of remembering that the self’s ultimate freedom exists, that literature derives its powers from memory. We know now that place cells in our hippocampi help us to navigate and map our way through the physical terrain of the world, that this is aided by the networks and circuits of episodic memory, also held in the hippocampi. Our ability to mentally place ourselves in the past and the future, through autonoetic consciousness, is considered an exclusively human trait, and it is tied inextricably to memory, which gives us footholds to our sense of self in time and space. Without it, we are unmoored, thrust into an unfamiliar landscape, adrift in a diary with no dates.

I watch a video of Pina Bausch’s choreography, Café Müller, and it seemed to express all the thoughts I’d been having about freedom with a multiplicity of bodies, music and movement

Abhinavagupta’s idea, though, goes beyond just the self. The notion of collective memory is particularly strong if you consider the vast corpus of oral literature in India, where the power of the word was in utterance and listening rather than the written text. Poet-saints like Kabir and Lal Ded most likely could not read or write, but that didn’t stop them from going into the world, singing their songs, which people memorised and internalised, writing them down only centuries later. To be a creator, then, was not to be a singular being with iron-clad authorship, but rather, a collective body politic from which songs emerged. Songs which were then embroidered and enlarged to hold all the centuries between them and us—a giant pulsating net of language in a continuous state of movement: many-bodied, many-tongued, many-memoried. If you consider how poems, particularly in the Bhakti tradition, were powered by the impulse to emancipate from the hierarchies of society—caste, religion, patriarchy; that it took a fearlessness to do this, then poetry can be seen as the ultimate freedom, something that privileges the inner experience as the real, deep, divine thing, while the outer world is seen for what it is—temporal, shifty.

AS A DANCER, I’ve felt those flashes of pure freedom that Nina Simone was talking about—the “no fear” moments on stage when you are both in communion with yourself, and somewhat outside yourself. As a writer, I’ve felt it too—wandering freely in an untrammelled landscape where I’m not marked by time or age or gender, but simply a collection of atoms afloat in a primordial soup of imagination. There are many ways for people to experience this feeling—meditation, drugs, climbing a mountain. The difference with performance is that it is an embodied experience, and your feeling of freedom relies upon the other bodies in the room who have collectively gathered there with a willingness to be transformed. It’s as though the presence of other bodies provides the agency, the power that elevates your sense of fearlessness.

The body, unfortunately, comes with a lot of baggage. So many philosophies suggest that we can only arrive at freedom by ditching the body. The sanyasin who casts off from this shore to erase all worldly markers, the cloistered monk who takes a vow of silence. This version of freedom has to do with release, dissolving, merging, letting go of ego and possessions that tie us down, so that boundaries, states, borders, dream, reality, inner, outer—all demarcations and dualities cease to exist. We could think of freedom and suffering as two mismatched siblings who always travel together in the cage of the body, rattling along at the expense of one another, so much so, that the only way to be truly liberated is to be effectively dead. If you’re of Buddhist, Jain or Hindu persuasion, there’s a freedom that trumps even death—nirvana, moksha. But what if you wanted to position the body, flawed as it is, as a harnesser of freedom? Rather than demote the body, what if we could centralise it and suffuse it with agency, and possibilities for renewal? What then might freedom be like?

I keep circling back to these four touchstones—body, language, fearlessness, power—how the key to freedom lies in these shifting sands. The thing about earthly freedom is that it is not a stable emotion or state. It relies on movement. In its most illuminated condition, freedom is a flash of momentary unity—of self with self, self with another, self to universe. But mostly, it’s a tussle, in the process of happening, often accompanied by violence. The problem with freedom in its long and complicated history, is that freedom for some has frequently meant oppression for others.

This is why freedom is often accompanied by words like struggle, fight, resistance, revolution. Freedom is a struggle for power. Leo Tolstoy’s A Letter to a Hindu (1908), which prescribes the practise of love as an alternative to violence, a resolute non-participation in evil in order not to be enslaved, was one among many of Tolstoy’s writings that inspired Gandhi’s ideas for Satyagraha and India’s Independence Movement, which later inspired Martin Luther King Jr and the Civil Rights Movement in the US. Tolstoy calls those who advocate violence “enemies of truth”. His suggestion? Free the mind from the imbecilities of pseudo-religious nonsense: “Do not resist the evil-doer and take no part in doing so… in the violent deeds of the administration… and no one in the world will be able to enslave you.”

As radical as nonviolence is as a philosophical and political idea, it does not get to the root of why humans are so fundamentally violent, and why they need to degrade and strip other humans of their freedom. A few days ago, I walked into the gates of Dachau, a former Nazi concentration camp, where this sign hangs on the gate: “Arbeit Macht Frei” (Work Will Set You Free). Primo Levi, in his memoir, If This Is a Man, narrates his experiences as a prisoner in Auschwitz, where the same sign hung over the gate. He remarks on the irony of those words, how the only way to be free in the Lager was to work to death. He describes how things that normally allow us to make our way in the world—body, language, time, name, memory—are systematically erased. “Guests of the Lager”, he writes, are divided into categories—criminals, politicals, Jews, who must wear striped uniforms with either red or green triangles, or a yellow star sewn next to their number on their jackets. Their heads are shaved and within weeks, if they are still alive, they are emaciated, speechless skeletons. “For us history had stopped,” he writes. “When we do not meet for a few days, we hardly recognize each other.”

This planet is full of killing fields. Not all are so meticulously preserved to remind us of our atrocities. But because we are human and are always seeking to understand the story of ourselves, we need to acknowledge that a violent erosion of freedom of others has been at the heart of our narrative, whether it’s the branding of people by slave-owners, the tattooing of numbers on prisoner’s arms, female genital mutilation, and forced sterilisations. The body is the first place where freedom is wrested, and with that comes a failure of language. How can you have faith in language when language holds a word like “blutgraben” (blood ditch), which runs alongside the execution range in Dachau? Where do you find words to speak back to this systematic dismantling of free will? The reason trauma is so often accompanied by wordlessness is because speaking would mean reliving, which is why survivors of rape and abuse find it difficult to speak about it, people who have fled genocide don’t want to talk about what they left behind. To allow the words to spill out might mean to slip back into horror and be swallowed by it. And yet, in order to bear witness, we eventually reach for language.

A FEW YEARS AGO, I walked around Jaffa with my friend, the Palestinian poet, Asmaa Azaizeh. We ate brunch on a beautiful beach, and amongst the stones on that beautiful beach you could still find bits of rubble from the Palestinian houses that had been bulldozed. Asmaa told me she believed bodies carried intergenerational trauma, that even though she had grown up in a peaceful village and had never seen a shooting in her life, she still feels part of the collective memory and collective survival of the 1948 Nakba. Even though she had never met either of her grandfathers, they kept turning up in her poems. There are always gaps, she said, among political ideologies, reality, the past, legitimacy. She said she can never be satisfied because no matter what she does, these gaps persist. What does it mean to build your life on the rubble of someone else’s home, or to forcibly take over someone’s home, which is what settlers are doing in Sheikh Jarrah today? What shape can freedom take in a place like this?

In Jerusalem, I had expected to feel a sense of holy that such nodal places are meant to radiate, but all I felt was terror—layer upon layer of unrest and injustice. I wanted to get out of there. These past few months I have watched videos coming out of Sheikh Jarrah, where mobs chant “Death to Arabs”, where a settler from Brooklyn justifies taking over a Palestinian home because if he didn’t do it, someone else would. In the faces of those mobs, I recognised something I’d seen in the horrific videos of lynchings in India—of Muslim men being bound and forced to chant “Jai Shri Ram”, of Dalits being whipped for skipping a day of work. There is power in the faces of those meting out the violence, but there is also disgust and fear of contamination. James Baldwin, describing the scenes of “Freedom Day”, the Black voter-registration drive in Selma, Alabama, in 1963, said that the police who were moving the crowds along were like parrots, repeating the same words again and again. “When I finally looked into their faces, they were terrified,” he said. “With their guns and helmets. And terrified in a strange way. Terrified as the mindless are terrified. Because the only way they could react to any pressure was a rock or bullet or gun.”

The difference with performance is that it is an embodied experience, and your feeling of freedom relies upon the other bodies in the room who have collectively gathered there with a willingness to be transformed

It’s the same terror that makes rich people build impenetrable walls around their homes; of hetero bodies inflicting violence on trans bodies; of governments who spy on their citizens, and fine women for wearing burqas, and fine them for wearing shorts instead of bikini bottoms; of rapists who see no dignity in the bodies they violate; of the hundreds of earthly limbos that have been created in the refugee camps of Bangladesh, Syria, the Congo, and the statelessness of places like Kashmir and Tibet, where bodies are perched in a kind of hell for decades. Where there is no whisper of freedom on any horizon. There is so much terror in the bodies of the oppressed and the bodies of the oppressors, and yet, the body is what we must return to.

Increasingly, I begin to think that freedom can only lie in multiplicity. The “Free World” has given us rampant capitalism, which has promised all kinds of freedoms but has trapped us in a hyper-individualist, consumerist, climate-nightmare idiocracy, where our sense of freedom trumps any sense of community. To assert one’s freedom has become so enshrined, we feel it must be pursued at all costs, even if it means risking your own life, or another person’s. This is a dead end to freedom because even though we arrive and depart this earth alone, we share this space with other bodies, and for freedom to be free of terror, it needs to be capacious, many layered. I think of the hundreds of personas the writer Fernando Pessoa created for himself—heteronyms, he called them, each complete with their own biographies, personalities, physical and philosophical traits. “Each of us is several, is many, is a profusion of selves… In the vast colony of our being there are many species of people who think and feel in different ways” (The Book of Disquiet). I saw a manifestation of this in Koovagam, a small village in Tamil Nadu which hosts India’s largest transgender gathering, which I visited in 2006. All around me, a hologram of bodies—beyond male or female, a heaving mass of power that was both spiritual and sensual and entirely non-threatening. You can see it in the thrum of bodies that take to the streets in protest—in Beirut, Belarus, Myanmar— how different it is from the bodies in a mob. One is an abomination. The other is like a murmuration of starlings with one strong beating heart.

WE LIVE IN AN age of great surveillance—one camera for every seven people on the planet. Technology has promised greater connection and freedom, while reducing our boundaries of privacy. The internet offers a kind of disembodied intimacy and anonymity which has provided platforms for hate speech and fake news to proliferate like blooms of algae. Evidence suggests that our over-reliance on smart phones is making us somewhat less smart—our hippocampi are atrophying, and our means of mapping our way in the world now involves following a moving blue dot on a screen, rather than regarding the terrain around us.

In 1973, Alexander Solzhenitsyn warned of the dangers of a totally controlled state society, of what the jamming of radio broadcasts might mean to those who hadn’t experienced it. “It means spit in our ears and eyes every day; it degrades the self to the condition of a robot;… it means trimming down adults to the level of infants: one must eat only mother’s baby food.”

Freedom, contrary to what the word implies, seems to have an inbuilt need for resistance, pushing back, confrontation. When we walked into Dachau, my husband burst into tears. “Sorry,” he sputtered, “I don’t know if I can do the horror show.” Primo Levi, after surviving Auschwitz, managed to express what he thought language could not do—find words to describe the demolition of a man. Perhaps freedom is about a new way of seeing, as Nina Simone suggested. The Bhakti poets were called sakhis after all—seers, those who witness. Freedom is about seeing and being seen, about recognition.

After returning from Dachau, in our hotel room in Munich, I watched a video of Pina Bausch’s choreography, Café Müller, and it seemed to express all the thoughts I’d been having about freedom with a multiplicity of bodies, music and movement. The idea of resisting the robotic, of who we are in relation to each other, of how tiring it can be to be alive in whatever body you happen to possess. Bausch apparently liked to sit in cafés to build her images, and for this piece, the stage is filled with tables and chairs. She is a ghostly figure at the back of the stage in a long slip dress, and looks to be wearing an invisible straitjacket, arms held out in an act of pleading and sorrow. A woman in heels click-clacks across the stage, constantly in search of something. A man and woman try to hold one another, while another man looms behind, forcefully rearranging the woman’s limbs. Another couple takes turns to throw each other against the wall. There is much clattering, stumbling, searching, silence, and there are moments of unity, embrace, tenderness. Perhaps those are the windows of freedom—those moments when you can let go of your breath. When you can hold and be held.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Nimisha Priya’s Fate Hangs In Balance, As Govt Admits It Can’t Do Much Open

Roots of the Raga Abhilasha Ojha

An Erotic Novel Spotlights Perimenopause Nandini Nair