Madhuri Dixit: The Return of the Queen

Madhuri Dixit set the template for the modern-day heroine in Bollywood and now she is back to challenge it in a new series that casts her as an ageing diva

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

Kaveree Bamzai

|

25 Feb, 2022

|

25 Feb, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Queen1.jpg)

Madhuri Dixit in The Fame Game

THERE’S A MOMENT in The Fame Game, Netflix’s new series starring the iconic Madhuri Dixit, when a young actress walks up to her and seeks her blessings, telling her how she and her mother are huge fans. The famous smile becomes icier with every word, and Madhuri, who is playing an ageing actress, says with a laugh: “You young stars have everything. PR, stylists, trainers. Actually you don’t even need talent, let alone my blessings.” The sarcasm is lost on the younger woman, as Madhuri aka her character Anamika Anand moves on.

It’s happened to Madhuri in real life too. She recounts the latest such incident with a laugh: “It’s funny when we were launching the trailer, Bejoy (Nambiar, the co-director) said the first time he saw me was when he was in school, and I said, when you were in school, so was I, working in films.” Indeed. Madhuri, who will turn 55 this year, began in Abodh in 1984, playing a naive, pigtailed villager who marries Tapas Paul but doesn’t understand what it entails. Just for context, the three Khans, her contemporaries, made it big on the small and big screens four years later.

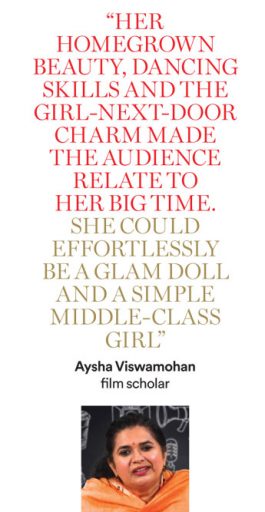

“I don’t dwell on the past. I want to do something more, something better,” says Madhuri Dixit

She has been through the worst phase of the film industry, when women were infantilised, given bows and bands in their hair, made to wear shimmering pink lipstick and glittering blue eyeshadow, and given costumes fit for plastic dolls. She has survived rumours of affairs (with co-star Sanjay Dutt), a terrible case of acne, a kissing scene in Dayavan (1988) which she regrets to this day, and a media that wrote her off as often as it declared her the new No 1. Yet she survived and thrived, setting the template for the Hindi film heroine: homegrown beauty, dancing skills and a girl-next-door charm which made the audience relate to her. As film scholar Aysha Viswamohan says, Madhuri owned the 1990s. “One has to be part of a generation that has witnessed her blockbusters like Dil (1990), Beta (1992) and above all Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! (1994) to understand the Madhuri magic. She could effortlessly straddle the boundaries between being a glam doll and a simple middle-class girl. She was the last of the female stars who ruled the single-screen theatres,” she says.

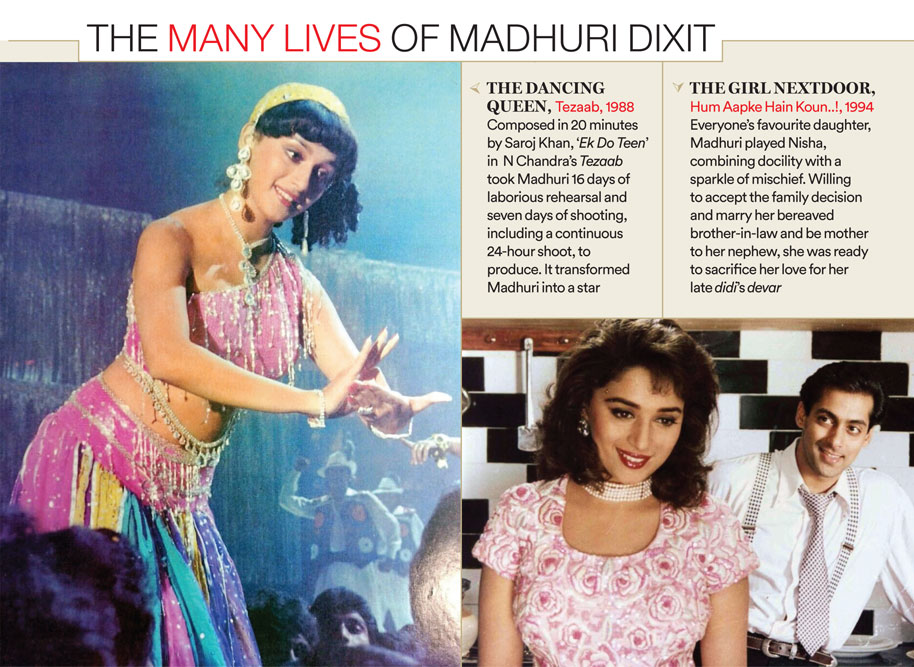

Madonna and belladonna. Sati Savitri and seductress. The emblematic actress and the item girl. There are many Madhuris. There is Mohini from Tezaab (1988) dancing for her alcoholic father; Nisha from Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! sacrificing her love for the family; Pooja from Dil to Pagal Hai (1997), in a sleek leotard engaged in a dance-off with the svelte Karisma Kapoor; Anjali from Pukar (2000), ready to spy and die for her beloved; Begum Para in Dedh Ishqiya (2014), making Naseeruddin Shah’s Khalujaan, Vijay Raaz’s Jaan Mohammad and Huma Qureshi’s Muniya fall in love with her. And now finally as Anamika in The Fame Game, staring into her lover’s face, telling him it’s time for her to do something for herself.

“It’s great to have fans in all age groups, whether mothers or kids, grandparents or grandchildren,” says Madhuri Dixit

Ageless. Timeless. Peerless. In a career spanning 38 years, is it any wonder we have so many Madhuri Dixits to reclaim and revisit? And then there is the Madhuri of the dance contests, the online dance platform she has launched, and the Instagram reels, dancing like no one is watching, smiling to fans, cooking with her husband, singing with her older boy, and now even wanting to learn tennis. “I don’t dwell on the past,” she says, her 12 years in the US echoing in a faint twang. “It’s done, let’s move on. I want to do something more, something better all the time. There’s always something new to learn,” she says, sitting in a white pantsuit, one leg propped up on the chair, the other swinging slightly, her high heels abandoned. She is the picture of grace, comfort, ease.

It wasn’t always so.

She started out as a nervous newbie with two pigtails and thin arms in Abodh at the age of 17, and would have remained a footnote from a forgotten film had three men not decided to reinvent her career. They released a six-page ad in the film weekly Screen, listing the names of eight directors who were keen to work with the young actress. Despite five flop films before this, the announcement gave Madhuri the sheen of a newcomer. The men: producer Boney Kapoor; his brother, actor Anil Kapoor’s secretary, Rakesh Nath; and director Subhash Ghai, then at the height of his fame, who had picturised a song on her in Karma (1986) and then edited it out, but then shot a showreel for Madhuri and sent it to the directors.

Each of the three men would play a significant role in the legend that Madhuri became. But it was a fourth person, a woman, who would give form to the allure these men saw in the slim, young aspiring microbiologist. And predictably for Madhuri, it was a dance that made her a star. ‘Ek Do Teen’, a song written by Javed Akhtar, is set almost at the beginning of N Chandra’s gritty Tezaab. Composed in 20 minutes by Saroj Khan, it took Madhuri 16 days of laborious rehearsal and seven days of shooting, including a continuous 24-hour shoot, to produce. For her, “It was like a classroom.” She learnt how to dance for the camera with this song.

Energetic, vigorous, expressive, the song, shot in Mehboob Studios, transformed her into a star. The sweet smile combined with the heaving chest, the exaggerated swaying of the hips and the pelvic thrusts created a new kind of heroine who could subsume the function of the vamp. The big hair, the glittery costume, the elaborate stage were usually elements of the vamp’s repertoire. But Madhuri brought to it a charming innocence which was all Saroj’s doing. Writing in February 1989, film critic Madhu Jain called the film the dark horse of 1988 and ascribed much of its success to the song which is “driving people crazy. Ek do teen, they hum from the shower to the office, from the office to the bedroom and everywhere else in between.”

“I had a hairdresser, a make-up artist, and my mom. Now we have a social media team and so many teams that follow us. Now you need a whole village to create a star,” says Madhuri Dixit

The dance marked a turning point in the history of Hindi film dance for several reasons, writes gender and sexuality scholar Paromita Vohra. For the first time, it presented a clear heroine figure in a dance that is chiefly sexy, and presented sexiness with a robust, bodily series of steps. From this film on, a Madhuri Dixit film meant there had to be a Madhuri Dixit dance item in the film. The songs were full of double meanings and suggestions, as well as winks and teasing steps: ‘Humko, Aaj Kal Hai Intezar’ in Sailaab (1990) with its Koli fisherwoman style; ‘Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai’ in Khalnayak (1993) with its Rajasthani flavour; ‘Chane Ke Khet Mein’ in Anjaam (1994) and ‘Didi Tera Devar Deewana’ in Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! with their Uttar Pradesh folk roots—all of these featured much heaving of breasts, sticking out of bottoms and sinuous hip movements. Saroj also developed the signature step, which was repeated along with the refrain of the song, and through which cinema culture became physical culture, allowing those watching to imitate the dancing bodies, says Vohra.

Saroj was as focused on Madhuri’s face as her body. Though she had never been classically trained, Saroj had understood the fundamentals of Kathak and Bharatnatyam over her years as a group dancer and assistant choreographer. She poured all her learning into ‘Ek Do Teen’ and into Madhuri. She introduced sensuality, distinct from vulgarity, in the traditional Bollywood dance, skirting the line between pure classicism and cinematic

extravagance. Saroj didn’t just dance with her body, she danced with her soul. And she made Madhuri a star. Madhuri recalls the time: “Every producer wanted me to do a dance number in his or her film…We were shooting a song for Tridev. There were three actresses. Sonam was a bigger star and so, she was made to stand in the centre. But as soon as ‘Ek Do Teen’ became a hit, the producer changed our positions. I was in the centre.”

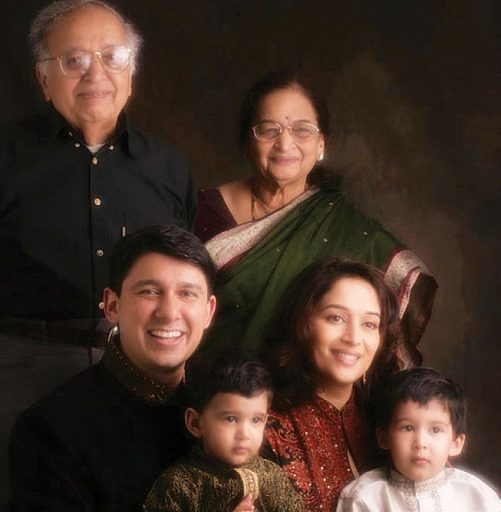

Her frequent co-star from that era, Anil Kapoor, with whom she shared the once powerful Rakesh Nath, says he doesn’t want to take any credit for her career. “She has made it on her own, with the support of her wonderful, dignified and simple parents; she’s gifted and a born actress who blossomed into a big star but she will always be a daughter, wife, mother, and a dear friend. A fabulous dancer with a million-dollar smile.” Their friendship has endured since 1985, even when she married cardiac surgeon Dr Shriram Nene in 1999, went to Gainesville, Florida, and then Denver, Colorado, and lived in the US for 12 years before moving back. It has weathered storms, including rumours of discomfort caused by Madhuri’s rivalry with the other great female star of the era, Sridevi, who eventually and controversially married Boney Kapoor in 1996. Madhuri shared the throne with Sridevi for a while and then came the blockbuster Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! that made her the nation’s sweetheart. By 1994, she had toppled Sridevi from her No 1 position and was on the cover of practically every magazine with her radiant smile.

“I’ve grown up in a very sheltered environment. My mom has always stood by me. Anamika Anand is completely the opposite,” says Madhuri Dixit

It is difficult to imagine how many hearts Madhuri broke when she married cardiac surgeon Dr Nene, whom she was introduced to by her brother in the US. Deepika Padukone once laughingly recounted in an interview how her father, badminton star Prakash, locked himself in the bathroom to mourn her marriage. Madhuri’s reversal of fortune coincided with the arrival of women who had won global beauty events. By the late 1990s the definition of ‘beauty’ had changed forever and had paved the way for a different kind of heroine who fit the requirements of a more international kind of screen presence, points out Viswamohan.

Madhuri’s ethnicity had a lot to do with her rise, says veteran film critic Maithili Rao. Maharashtra had waited a long time for a Marathi mulgi (girl) to rule the industry as its prime diva, says Rao. “After Nutan, an accomplished actor with gravitas, there was a palpable underlying angst that none of their own rose to be the reigning queen in the city of dreams,” says Rao. Madhuri is perhaps the best dancer we have had, with her natural grace, infectious joie de vivre and intuitive ability to make the erotic acceptable. ‘Choli Ke Peeche’ in Khalnayak is the most famous (infamous?) example of cinema as the most powerful tool to empower the male gaze. Sanjay Dutt’s eyepatch emphasised visual pleasure that catered to male fantasy. Its risqué lyrics and celebration of rustic raunch outraged many puritans but Madhuri’s shapely shoulders shrugged off any charge of obscenity, notes Rao.

Despite ‘Ek Do Teen’ and ‘Choli Ke Peeche’ being synonymous with her rise to fame, the Madhuri paradox cast her in the image of the good beti-bahu imbued with family values. “Nisha of Hum Aapke Hain Koun..! is everyone’s favourite daughter, who combined docility with a sparkle of mischief. Willing to accept the family decision and marry her bereaved brother-in-law and be mother to her nephew, she was ready to sacrifice her love for her late Didi’s devar whom she teased and flirted with under their collective noses. Traditional families are blind. Of course, the family dog and devoted retainer save the day for the sacrificial pair of docile lambs but the point underlined is willingness to obey elders,” says Rao.

Similarly, she says Saraswati of Beta, in time, became the template of the bahu who righted wrongs done to her simpleton husband and taught the wicked step-sasuma a lesson for life. This story of a determined, intelligent bahu restoring the right patriarchal order has been a favourite trope of popular literature and films. Saraswati is not the coy bride of earlier films. Beta rechristened Madhuri as the dhak dhak girl where she seduces the innocent husband with her heaving breasts and alluring smile, creating her own path to justice. Madhuri is the feminine strong woman who uses her Mohini avatar with discretion.

And yet the 1990s’ women often dressed like girls, perhaps to match the men, who were boys. Remember Madhuri in Dil, with her long dresses, which can only be described as Barbie frocks, and the big hair? Madhuri grew up, but the Khan boys didn’t, moving on to ever younger heroines in an effort to remain evergreen. It was a time when women were girls on the set too, with the ever present Mummy. Madhuri, too, was accompanied everywhere by her mother, even to parties where the men and women were segregated. One actress of the era remembers attending parties where the men drank in one room while the women sat, usually with their mummies, talking desultorily in another room.

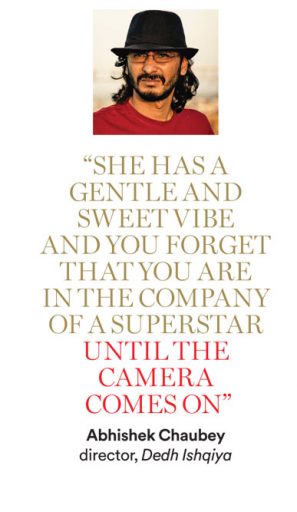

Unlike Anamika Anand, Madhuri was never forced into the film industry. She chose to make it hers because she loved the work. “Whatever I did was because I wanted to,” she says. She is the gold standard for heroines, the perfect balance of wholesome goodness and secret sensuality, of little-girl innocence and womanly wiles, of perfect professionalism and easy warmth. Jaideep Sahni, who wrote her comeback vehicle, Aaja Nachle (2007), where she played a 40-something divorcee with a young daughter who returns from the US to her village to revive her guru’s theatrical troupe, says working with her is the same as Shah Rukh Khan. “It spoils you for life. They are just such consummate professionals.” Abhishek Chaubey, who helmed Dedh Ishqiya, says it was a breeze working with her: “She has a gentle and sweet vibe and you forget that you are in the company of a superstar until the camera comes on and her immense talent speaks for itself.”

But she isn’t all sweetness and light. She has no time for excessive flattery. Incompetence irritates her too. “If everyone in this world did what they were supposed to do, wouldn’t it be a wonderful place?” she asks. Anger is not a totally unfamiliar emotion to her, but it takes some doing she says to get her really upset: “I’m a calm and patient person by nature.”

Madhuri loves the freshness of the streaming series. As she says: “‘It’s not just that Anamika is based in the film industry but it’s her relationship with her family. Her mother, her husband. That was fascinating to me because I’ve grown up in a very different, sheltered environment. My mom has always stood by me. Anamika Anand is completely the opposite. She did things because her mother was so domineering and now that she has everything, she doesn’t want to lose it. She’s clinging to it.”

Madhuri’s father ran a workshop making switchboard control panels and handled her finances, while her mother, a trained classical vocalist, was always there to support her, to pep her up when she was down: “I always had her. But there was no one else to guide us. I was just fortunate to get good directors and good roles,” she says. Madhuri the actor has been through some rough times. There were no vanity vans to retreat to, there were rarely air conditioners, the shifts were long, and sometimes there were two in a day, and there was no entourage to protect the star. “I had a hairdresser, a make-up artist, and my mom and sometimes my manager would drop in to see, ‘Sab theek chal raha hai na?’ That’s it. Now we have a social media team and so many teams that follow us wherever we go because that is the world we live in right now. I don’t see anything wrong in it because everything matters now. What you’re doing on social media, what you’re doing on the set, how you look, what you’re wearing. Now you need a whole village to create a star.”

What’s new is also the number of women on the set. “When I began the only women on set were me, my mum, my female co-stars and the hairdressers. That’s it (remember even make-up artists were a male preserve until 2014 when Charu Khurana took the matter to the Supreme Court). But today, when I walk on to a set, there are female assistant directors, directors, cinematographers, there’s a woman in every department. Writers, photographers, it’s so heartening to see them making a mark,” she says.

Madhuri seems remarkably sanguine about ageing. “It’s great to have fans in all age groups,” she says, “whether it’s mothers or kids, grandparents or grandchildren.” She’s a mom first and last. “Fame is great but your kids are your legacy finally. You’ll always be protective of them. You’ll always love them and you’ll always stand up for them and give your life for them. That’s what Anamika is as well, a tigress who wants to protect her children at all costs but who also loves them for who they are, unlike her mother (played by Suhasini Mulay) who wanted her to be a particular way.”

The time away from India gave her perspective. “I chose to do that. I met Ram and decided this is the man I want to marry and I did. It was something I had dreamt for myself, having a house, a husband, kids. It was a big part of my dream for myself,” she says. First they lived in Gainesville for two years, and then in Denver for 10. “Coming back was also an eventuality. My parents were getting old, I thought it’d be great to have the boys (Arin, 19, and Ryan, 17) grow up in India. Culturally, it was much richer for them,” she says. “They learnt the tabla, the piano; it was great to give them the art and culture that we have. Coming back was a great journey; I started working again. It was not planned, just organic.” She talks about her supportive husband, her mother-in-law especially who is a career woman herself (she’s a real estate agent). “My mom is a classical vocalist so I always had the art in me. I had this support system. Whenever I think of other women, I do hope they have this kind of family behind them,” she adds.

Madhuri doesn’t regret returning to India. Her children got pampered by their grandparents Aji and Azoba; they had cousins to mingle with. “They got to know their people, so they had a good time,” she says. Her husband is happy too—he always had a connection with India. He used to visit his grandparents in Dadar when he was little. Their online academy, Dance With Madhuri, which he manages now, has taken off, and both are passionate about it. “Accessibility to good gurus is limited. There is a time and cost constraint. But at Dance With Madhuri, you can come and learn dance at your convenience from the privacy of your home. It is in 199 countries, we have an audience everywhere. We have a community of artists who can converse with each other. I wish Anamika had done that,” she says.

When she’s not Anamika, she is with her boys, talking to them, sharing something with them, or she is with her husband—“Either we’re going out or hiking or skiing.” “I have this new thing,” she says, “I want to learn tennis because I love the sport. I’ve watched Billie Jean King, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Steffi Graf over the years. There’s always something new to learn.”

And that is the secret to her enduring appeal. At the heart of the goddess is a diligent, dutiful and dedicated student.

/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Cover_Double-Issue-Spl.jpg)

More Columns

The Music of Our Lives Kaveree Bamzai

Love and Longing Nandini Nair

An assault in Parliament Rajeev Deshpande