A Star for Everyone Anytime

THE EYES, NOW RIMMED WITH SLATE GREY because of age, have seen it all. They've seen the cruelty of a public that can go from adoring to flinging shoes at him in an instant. They've seen frailty, in himself, when he was at death's door in 1982, and in others. They've been hurt, angry, happy, twinkling, even joyous. But they've always been quicksilver, in downing the shutters, closing for the day, retiring for the night, going from Arctic to tropic. Shielding private trauma, they have always projected what the public wants them to.

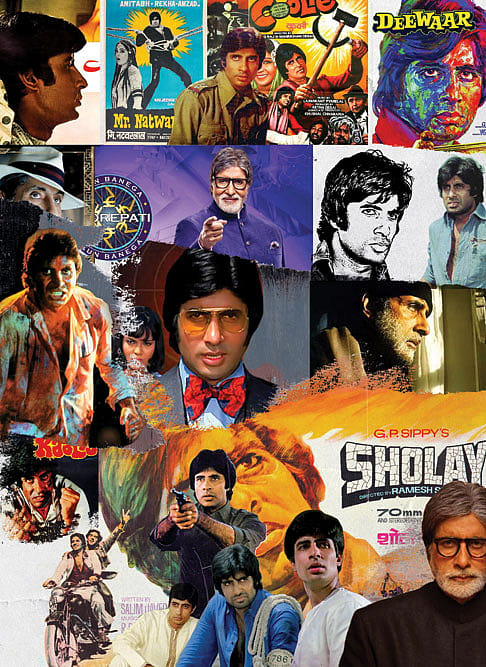

Superstars are beloved for the personas they create on screen. So is Amitabh Bachchan, the mischievous Jai of Sholay (1975), the brooding Amit of Kabhi Kabhie (1976), the resentful Vijay of Trishul (1978), the emotional Raj of Baghban (2003), and the pernickety Bhaskar of Piku (2015). But Bachchan is perhaps one of the few who are as beloved for who they are offscreen. Towering over the crowd, literally and figuratively, he has been part of our cultural fabric, invariably correct, utterly civilised, forever in control, Bachchan is a man who has educated us in how to be Indian. With his beautifully enunciated Hindi (he is one of the few actors who ask for the script in Devanagari) and his public school English, he has taught us how to straddle our divided bilingual selves. With his deep respect for traditions and his childlike wonder at the technology of the moment, he has enabled us to look back in wonder and look forward with curiosity. With his youthful rage and his graceful ageing, he has shown us how to negotiate our lives. As much Bharat, he is also India, a rare combination possible because of his philosophical, poet father, his can-do Sikh mother, and an education that began in Allahabad, continued in Sherwood College, Nainital, and Kirori Mal College, Delhi, where Frank Thakurdas taught theatre. Add to that a six-year-long boxwallah career that took him to swish clubs, lush golf courses and swinging restaurants of posh Calcutta.

He is also a man who has taught us the value of failure, whether it was the 12 flops that got him to Zanjeer, the 15-year war of silence with the film press, the close encounter with death in 1982 or the near bankruptcy after the debacle of the Amitabh Bachchan Corporation Limited (ABCL). For today's fifty-somethings, he is a reminder of their youth, and a showcase of their best selves to their children. Actor, big brand selling 21 smaller brands, daily examiner of our intelligence, Bachchan has been our co-passenger, watching over us as we watched him onscreen, singing to us, dancing for us, articulating our deepest, darkest thoughts, giving us the words to quarrel with our gods, the poetry to romance our loved ones, and the chutzpah to brawl with those who challenge us.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Most amazingly he has done this with sustained poor health. The left shoulder droops, the result of a surgery on a benign cyst in 1964 that accidentally left him without a nerve. Having forgotten how to walk after the 1982 accident on the sets of Coolie, it took him three months of intensive therapy at the Tania farm in Mehrauli, Delhi, to get back on his feet. A year later, when he was going up the stairs of his hotel room in Mysore, his legs refused to carry him. He could not swallow liquid. He would comb his hair and his hand would drop. Later, at Diwali, a firecracker exploded in his left hand, which had to be restructured from the wrist up. It took a month of exercises before his fingers could touch each other. The blood we see in Sharaabi (1984) when the glass breaks in his hand is his own. As if that were not enough, he occasionally sees a bright flash in his right eye. Doctors have diagnosed it as a gap between the retina and the cornea—it can't be treated.

IT IS THE same with myasthenia gravis, the muscular dystrophy which is incurable but manageable. He has bodyguards to defend his body, he often says, but he needs doctors to defend him from his body. There are always two doctors on call within close proximity of where he is, especially given the complications-causing surgery that was conducted on his intestines in 2006. His body, he is the first to admit, is a war zone.

What makes him so correct, in the way he carries himself, articulates himself, and expresses himself off screen? Is it a role he plays? Is the real man the one who enjoys eating in solitude even in a public restaurant, who slumps into his seat when he thinks no one is watching (although someone always is), who always answers his own emails, and who always responds to texts and messages even if a few days late. He is also a man deeply wary of the media, recording his interviews with his own team, staying away from political commentary, and shushing all talk of an 80th birthday celebration as "unnecessary fuss".

Yet, he is insecure about his stardom, worried that one Sunday the crowds will not turn up for their weekly darshan at his Juhu home. They haven't. Hundreds of films down, and he is still anxious about his lines, worried about his performance and intent on perfection. It could mean asking the director to cancel a day's shoot because he hadn't got the "sur" (tone) right, or recording a voiceover again because he didn't like a particular word. On the sets of Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (2001), Bachchan did not speak to anyone for two days in preparation for the scene where he throws Shah Rukh Khan out of his home. In Baghban (2003), he worked for three days on the12-minute climactic speech, with old friend Javed Akhtar. This is a man who writes a blog post every day, who often corrects typos you may have made in your email, and who is meticulous about the words he uses.

And yet for all his riches, his homes, his expensive art, and his luxury cars, what is it about him that remains the embodiment of the middle-class ideal, where wisdom was prized over wealth, where slings and arrows of public derision were met with stoic silence, and where doors once closed, even of childhood friends in high places, were never knocked on again? Who knows what secrets his eyes keep, what suffering it has seen. As he once told me: "Everyone comes with his share of sorrows and joys. The sooner you realise that struggle is part of life, the better it is. My philosophy is simple, borrowed from my father: mann ka ho to achcha, mann ka na ho to bhi achcha [If you get what you want, it's good. If you don't, that's good too]."

Bachchan's second coming, as the "ageless patriarch", in his smoking jackets and tasselled loafers, is a gift, one rarely afforded to everyone. It not only saved him from insolvency, from becoming a shadow of his former self, a sort of latter-day Bharat Bhushan, the fine actor who lost almost all the wealth he made. But it also saved him from becoming a caricature of his angry young man image, romancing women quarter his age, like Dev Anand in his later years. When he did romance younger women onscreen, with sophistication in Cheeni Kum (2007) and somewhat sleazily as Sexy Sam in Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006), he did so with white in his hair and beard on full display.

It is a tribute to him that he keeps working. It comes from the insecurity of his near-insolvency but also what he calls the "little bit of indiscretion" of taking time off between 1992 and 1996, when he became an NRI, ran the 24-hour news and entertainment channel TV Asia in New York, experimented with music in London and established ABCL in Mumbai. But his longevity is also an ode to his loyal, cross-generational audience that keeps consuming him hungrily, whether it is to hear his little life lessons on KBC (reminiscent of the short lectures Ashok Kumar would give us on Doordarshan after Hum Log, 1984-85, but with cutting-edge panache) or to watch him be raging patriarch in this week's Goodbye.

For any young director or actor in the industry today, working with him is an all-important part of their resume. He is always open to new ideas and new stories, wherever it comes from. He is careful with the brands he endorses, aware of the backlash against products like paan masala. He is happy to lend his time to good causes, whether it was being a member of the Uttar Pradesh State Development Council in 2003 at the height of his friendship with the late Amar Singh, or endorsing Gujarat Tourism in 2010 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was the state's chief minister. These, he maintains, are apolitical acts, having been scarred forever by his stint as Allahabad MP between 1984 and 1987, when he left in a blaze of bad press about his alleged involvement in the Bofors scandal. He did not rest until he cleared his name in the case legally and beyond doubt.

He is still the one every star measures himself against. Even a man like Sanjay Dutt will dare not smoke in front of him, while Ranbir Kapoor will have an attack of nerves before talking to him at an event. He can be amiably chatty one day, mercurial and snappy another. But tease about it, and he can laugh it away—though the laugh can vary in its intensity depending on how deep in the stomach it is rooted.

The humility is not fake, it comes from what he once said to me in an interview: "When you have had a colossus as a father, how can you ever dream of thinking you are somebody?" But the joy he has given us, his fans, is endless. As his son Abhishek told me when I asked him for his favourite Bachchan scene or moment: "They're all my favourites. How do I choose? That's why in my mind he's the greatest." Hard to disagree.

Also Read

Amitabh Bachchan: Legend and Legacy ~ by MJ Akbar

The Cult of the Angry Young Man ~ by Ranjani Mazumdar

Role Moral ~ by Rachel Dwyer

Love, Loss and Longing ~ by Kaveree Bamzai

My Amitabh Moments ~ by Kaveree Bamzai