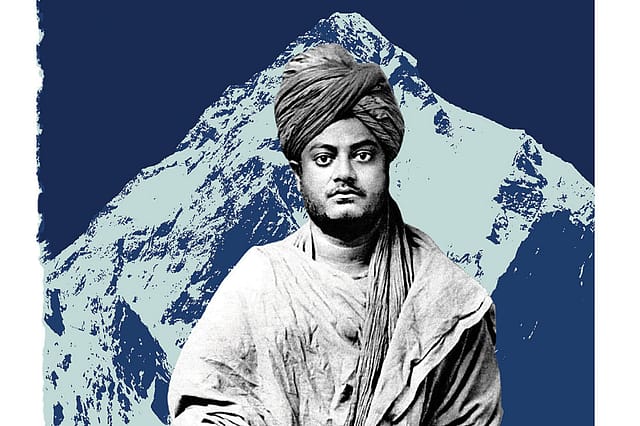

The Swami and the Himalayas

THERE IS SCARCELY an aspect of Swami Vivekananda's dazzling but brief life of less than 40 years that has not been studied. Yet his Himalayan connections demand further exploration. (Swami Vivekananda, 1863-1902, was one of the most powerful and influential makers of modern India. My study, Swami Vivekananda: Hinduism and India's Road to Modernity, HarperCollins, 2020, tries to demonstrate this at length.) Not only because his relationship with these majestic snow mountains was complex, multi-layered and enduring, but because some his major, lifechanging spiritual experiences occurred amidst the heights of Uttarakhand and Kashmir. (This is the first in a series that is an attempt to snapshot those crucial and momentous events in the Vivekananda's Himalayan sojourns because they continue to reverberate in the national consciousness to this date.)

The best place to start exploring Swami Vivekananda's special relationship with the Himalayas is, however, Kerala, in the deep south.

In his 'Reminiscences of Swami Vivekananda', KS Ramaswami Sastri recalls the nine days Vivekananda stayed at his home in Thiruvananthapuram in December 1892. The Swami was accompanied by a Muslim attendant and, at first, himself taken for a 'Mohammedan'.

Sastri, then 14 years old, recalls how one morning, when he was studying his textbook, Kalidasa's Kumarasambhava, he was asked by Vivekananda, "Can you repeat the great poet's description of the Himalayas?" Sastri recited the verses, so well-known, that open the Mahakavya (great poem):

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

astyuttarasyāṁ diśi devatātmā himālayo nāma nagādhirājaḥ |

pūrvāparau toyanidhīvigāhya sthitaḥ pṛthivyā iva mānadaṇḍaḥ | | 1.1 | |

The couplet may be rendered thus: 'In the northern direction, forming the heartland of Gods, stands the overlord of snowy mountains, Himalaya, like a measuring rod of earth thrust betwixt eastern and western oceans.'

Vivekananda remarks, "Do you know that I am coming after a long stay amidst the sublimity of the Himalayan scenes and sights?" So saying, he asks the boy to repeat the opening verse, this time also explaining its meaning. When Sastri does so, Vivekananda says, 'That is good, but not enough.' Then, repeating the couplet in 'his marvellous, musical, measured tones', the Swami explains:

"The important words in this verse are devatatma (ensouled by Divinity) and manadanda (measuring-rod). The poet implies and suggests that the Himalaya is not a mere wall accidentally constructed by nature. It is ensouled by Divinity and is the protector of India and her civilization not only from the chill icy blasts blowing from the arctic region but also from the deadly and destructive incursions of invaders. The Himalaya further protects India by sending the great rivers Sindhu, Ganga, and Brahmaputra perennially fed by melted ice irrespective of the monsoon rains. Manadanda implies that the poet affirms that the Indian civilization is the best of all human civilizations and forms the standard by which all the other human civilizations, past, present, and future, must be tested. Such was the poet's lofty conception of patriotism."

This extraordinary explanation not only underscores Vivekananda's great erudition and deep study of classical Indian literature, but, even more remarkably, his love of the Himalayas as a symbol of India.

To Vivekananda, India was one—from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. Sastri reminisces, 'I felt thrilled by Swamiji's words. I treasure them even to this day, and they shine in my heart even now with an undimmed and undiminished splendour.'

After Sri Ramakrishna's death on August 16th, 1886, Vivekananda had stayed mostly at the Baranagore Monastery for two years, consolidating the order of young sanyasins (renunciates) that he founded. His itinerant days began 1888, taking him all across the country, as a wandering monk. That year, he had reached as far as Rishikesh in today's Uttarakhand, but had to return because he contracted malaria.

But in 1890, Vivekananda set out again. So eager was he 'to see the snow-capped Himalayas', that he did not tarry in the sacred city of Varanasi. Instead, he predicted to his host, Pramadadas Mitra, "When I shall return here next time I shall burst upon society like a bomb-shell, and it will follow me like a dog!".

Vivekananda travelled extensively in the Himalayas, going on foot from Nainital to Almora, thence to Rudraprayag, Srinagar (Garhwal), Tehri, Mussoorie, then back to the plains via Rishikesh, Hardwar and Dehra Dun. There were two notable incidents in this period that bear emphasis.

Towards the beginning of their Himalayan sojourn, the group stopped near a watermill by a stream in Kakrighat, 40 km from Nainital. Under an ancient peepal tree, Vivekananda sat totally absorbed in meditation. When he came to, he declared to Akhandananda, "Well, Gangadhar, here under this banyan tree one of the greatest problems of my life has been solved." (Gangadhar Ghatak, or Gangopadhyay, was Swami Akhandananda's pre-monastic name. In those days, Swamiji too went by other names, including Vividishananda; Vivekananda became his stable moniker later.)

This was one of his great realisations, jotted down in Bangla in his notebook:

'The microcosm and the macrocosm are built on the same plan. Just as the individual soul is encased in the living body, so is the Universal Soul in the Living Prakriti [Nature]—the objective universe. Shivâ [i.e. Kâli] is embracing Shiva; this is not a fancy. This covering of the one [Soul] by the other [Nature] is analogous to the relation between an idea and the word expressing it: they are one and the same, and it is only by a mental abstraction that one can distinguish them. Thought is impossible without words. Therefore, in the beginning was the Word etc.

This dual aspect of the Universal Soul is eternal. So what we perceive or feel is this combination of the Eternally Formed and the Eternally Formless' .

Later, Swamiji would deliver his famous lecture on the same theme, 'The Cosmos: The Macrocosm', in New York, on January 19th, 1896.

During this journey, Vivekananda received a telegram informing him of the suicide of his sister. As Sister Nivedita puts it:

'[N]ews reached him, of the death, in pitiful extremity, of the favourite sister of his childhood, and he had fled into the wilder mountains, leaving no clue… it seemed that this death had inflicted on the Swami's heart a wound, whose quivering pain had never for one moment ceased. And we may, perhaps, venture to trace some part at least of his burning desire for the education and development of Indian women, to this sorrow.

Though these wanderings in the hills suited him temperamentally he was forced, as it were, to descend once more to the plains to engage with the toils and troubles of the suffering masses.

Later, he remembered renunciation and freedom of the 'stern ascetics' of the Himalayas: I saw many great men in Hrishikesh. One case that I remember was that of a man who seemed to be mad. He was coming nude down the street, with boys pursuing and throwing stones at him. The whole man was bubbling over with laughter, while blood was streaming down his face and neck. I took him and bathed his wound, putting ashes (made by burning a piece of cotton cloth) on it to stop the bleeding. And all the time, with peals of laughter, he told me of the fun the boys and he had been having, throwing the stones. 'So the Father plays,' he said' (The Master as I Saw Him by Sister Nivedita, Longmans, Green & Co, 1920, pp 98, 243-244).

In the same spirit, later in life, he declared in his letter of July 9th, 1897 to Mary Hale, one of his spiritual sisters, 'May I be born again and again and suffer thousands of miseries so that I may worship the only God that exists, the only God I believe in, the sum total of all souls: and, above all, my God the wicked, my God the miserable, my God the poor of all races, of all species, is the special object of my worship.'

(To be continued)