The Sublime Subversion of Ai Weiwei

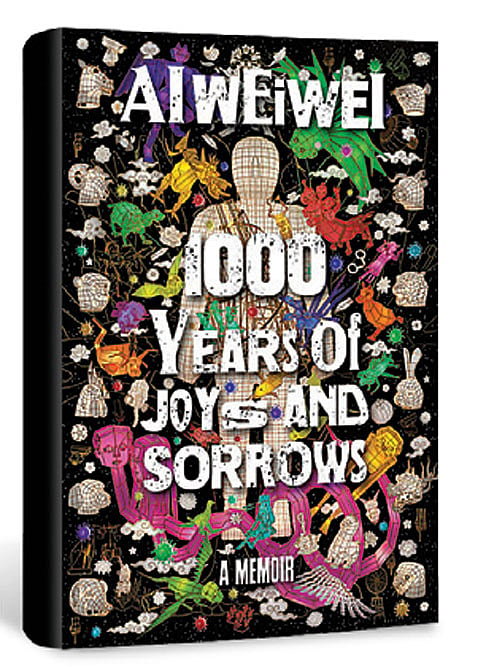

Ai Weiwei is an artist from a land that buries memory with brutal, digital precision. His art, born out of resistance and struggle, becomes one with his activism against a regime that failed to contain a rebel who always gave the middle finger to authority. He is an exile with the flamboyance of a postmodern shaman, the originality of a spontaneous debunker, and the ingenuity of an alchemist whom even his tormentors couldn’t figure out. He was the permanent puzzlement they couldn’t handle any more—or he was not worth the torture. So, in the end, they gave up and let him go—and created China’s own Solzhenitsyn, still imagining the home he lost in ways that defies conventions and complacency. “In the era in which I grew up, ideological indoctrination exposed us to an intense, invasive light that made our memories vanish like shadows. Memories were a burden, and it was best to be done with them; soon people lost not only the will but the power to remember. When yesterday, today and tomorrow merge into an indistinguishable blur, memory—apart from being potentially dangerous—has very little meaning at all,” he writes in his memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows (Crown, 400 pages, $32). Ai Weiwei remembers to regain the fragments of love and truth from a system that perfected the cruelties of ideology and the dehumanisation of power, and all the while finding secret methods to monitor the conscience of its wayward son. It failed. And the Artist Outcast is a living argument against the lies of the state. By remembering, Ai Weiwei, an exile still “drifting like duckweed on the current”, creates a semblance of freedom he and his father were denied in a China that was paranoid about shadows cast by the imagination.

The real beauty of this memoir is that Ai Weiwei is, in the best parts of the book, remembering on behalf of his father, a renowned poet and a victim of the Cultural Revolution. Shifted from one zone of punishment to another by what Milan Kundera would have called the autoculpabilization machine, peaking in his humiliation at a labour camp known as Little Siberia, Ai Qing was the original rebel who refused to wither away under Mao’s terror. He was a mind that Mao, as a revolutionary in the Yan’an caves, once admired. Ai Qing had dinner with him, and found Mao to be “thoughtful, composed, and widely read, quoting with ease from a variety of sources.” As a writer, he had his fears; he saw beyond the certainties of the revolution an oversized ambivalence, which he captured in a poem, blending hope with anxiety:

It's the Pits!

13 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 58

The state of Indian cities

No one could suffer more than me

I am loyal to the epoch and commit my life to it, but I am silent

Against my will, like a captive

Wordless on my way to execution.

In an essay titled ‘Understand Writers, Respect Writers,’ he wrote: “A writer is not a skylark, nor is she a singsong girl whose job it is to warble tunes to entertain her patron.” The songs Ai Qing sang in solitude would take him to the farthest recesses of communist horror. And the stoic would defeat socialism, finally.

It was a hard road for a poet who had the early privilege of being exposed to the West and feted by his admirers abroad, but in Maoist China, the onetime acquaintance of the Chairman was fast becoming a “rightist” worthy of “thought remoulding”. Neruda wrote of his old friend:

“Ai Qing belonged to the old Oriental stock of poets conditioned by colonialist oppression in the Orient and a hard life in Paris. Coming from prisons in their native land, these poets, whose voices were natural and lyrical, became needy students or waiters in restaurants abroad. They never lost confidence in the Revolution. Very gentle in their poetry but iron-jawed in politics, they had come home in time to carry out their destinies.” Ai Qing’s destiny would be determined by ideology’s quest for purity. He would be rehabilitated three years after Mao’s death, in 1979, when China was experiencing the initial reformist era of Deng, another survivor of the Cultural Revolution. Ai Qing continued to direct his poetic anger at all forms of fractured freedom. Ten years after his freedom, from the ruins of the Berlin Wall, someone would recite a poem he had written long before:

A wall, like a knife

Cuts a city into two

Half to the east

Half to the west

Ideologies partitioned the mind, and, like the father, the son would struggle, sacrifice, and overcome in the pursuit of finding the unity of artistic purpose in adversity. It is in his genes—the urge not to conform: “What I soon learned was that I did not fit in with the new post-Mao order any more than I had fit in with the Maoist order that had shaped—or deformed—my childhood.” A passage to America would change his perspective, but the West didn’t convert the rebel. When the plane circled above New York, as he “gazed down at the seething hallucinatory metropolis below, where traffic flowed like molten iron, all my motherland’s teachings, earnestly imparted over so many years, drifted away like smoke.” Little discoveries would have profound impacts, among them holding the book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again or a chance encounter with Allen Ginsberg, “a smouldering charcoal fire”, whose abiding memory of China was the big hug Ai Qing had given him. More than a decade after he left home, he would return—to a hell the regime had custom-made for him—and recover his identity as an artist by the sheer force of defiance: “Disdain is a chasm that no power can cross; it makes space for itself by subverting order.”

Ai Weiwei’s subversion would make him an iconoclast and an iconographer at the same time, daring the strictly coded social realism of the Party with the social morality of his own art. An exhibition he curated in 2000 was called “Fuck Off”, in which one photograph showed an artist chewing on the limbs of a human foetus, a protest against China’s one-child policy. At the 2007 Kassel Documenta Exhibition, he would travel to the German city with 1,001 Chinese. Fairytale was a symbolic flourish that captured, in the words of a critic, “the loss of culture and the impermanence of material possessions”, heralding his art’s social urgency. Whether it was a

poisonous milk powder or an earthquake that killed scores of children, events that confirmed the lurking Oriental beast beneath the manufactured idyll made Ai Weiwei a social activist—or made his art a visual scream for truth. At the Tate Modern, with one hundred million handmade sunflower seeds, he would multiply individual freedoms and turn the beauty of creation into a horrifying reminder of what is being lost in a totalitarian society. When art became a physical impossibility in the surveillance state, he hit the internet as a blogger dissident. When blogging became a crime against the state, he took to Twitter, making his digital banishment inevitable.

One morning in April ten years ago, Ai Weiwei was picked up from the Beijing airport and consigned to secret incarceration for the next eighty-one days. He would become a Chinese version of Winston Smith, but his re-education was a disaster, what with the ever-sensitive middle finger. Adding absurdity to his trial, on the day he was released, the investigator told him that everything he did was basically a form of Dadaism and cultural subversion was his speciality. “Duchamp had been a destructive fellow, too,” the investigator told him. It was not the life as a splash on the canvas of communism that Ai Weiwei wanted. So he fled China in 2015.

Once, in a video chat, his son told him that he had put a hammer in the freezer for him. “It’s a present for you. The hammer represents Ai Weiwei. No matter how much hassle he gets from the police, Ai Weiwei is always Ai Weiwei—he’s not going to change. When the ice thaws, the hammer is still hammer.” We read 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows at a time when the hammer held by the new helmsman of China threatens the world, but the gift preserved for a subversive father by a son is redemptive.

A metaphorically armed Ai Weiwei can now smash more icons.