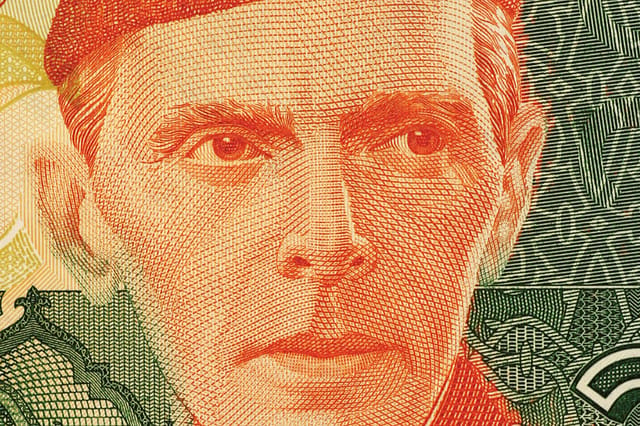

The Legacy of Jinnah

There was the urbane in Muhammad Ali Jinnah (whose death anniversary is September 11th). Steeped in modernity as he was, he could have been a prominent figure in the politics of the West, with which he liked to identify himself. And yet there were in him all those little instances of demeanour and outlook which rendered him petty. He refused to address Gandhi as the Mahatma, even though Gandhi had no qualms about honouring Jinnah as Quaid-e-Azam. And when Jinnah refused to shake the hand proffered by the scholar-politician Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, despite shaking hands with other (non-Muslim) figures of the Indian National Congress, he did himself no favours.

Seventy three years after the cataclysm of Partition and 72 years after Jinnah's death in what were clearly forlorn circumstances, there are those who go on arguing that had Jinnah lived longer, Pakistan would have transformed itself into a properly democratic, perhaps even secular country. It is logic that does not hold water. Worse, it is bad sophistry, if sophistry is what it is. Sit back and reflect on the reasons why.

The founder of the state of Pakistan found himself positioned, in August 1947, as an almighty individual in the political scheme of things. In the country he had fashioned through a violent exercise of communalism, helped not a little by the frenzied rush to decolonization by Mountbatten and company, Jinnah was governor general of the country, president of its constituent assembly and chief of what by then had become the ruling Muslim League. All authority was his, flowing from him and going back to him. Neither the constituent assembly nor Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan mattered.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

The seeds of autocracy that would in time be taken huge advantage of by Pakistan's military were what Jinnah planted in the early days of Pakistan. The cult of personality, set in motion by Jinnah, has grown in the subcontinent and has especially in Pakistan generationally undermined the concept of democracy. Once Jinnah passed from the scene, Pakistan went into a tailspin, a condition it has never been able to recover from. Democracy and Islam have proved to be a volatile mix for the country. The roots, of course, have lain in the spurious idea of the two-nation theory Jinnah and his Muslim League propounded so vigorously — and so ruthlessly — in the 1940s.

As stated earlier, Jinnah was a modern, urbane man steeped in the liberal traditions of the West. It was these traditions he brought back home from England, ideals he thought he could safely see transplanted in his colonized India. The future, in the 1920s and 1930s, appeared to be Jinnah's. And then, strangely, he lost the future through deliberately turning his back on it. The secular Jinnah, unable to agree with Gandhi and Nehru or stomach their brand of politics, turned inward and then parochial. Communalism was beginning to make inroads into his politics. In personal life, he was not given to small conversation or ordinary socialising. His mind, sharp in its perception of political conditions, would not go beyond legalities.

Jinnah detested academic discussions. And there is little hint of any attachment he might have had for aesthetics in the form of literature. Razor sharp politics was a consuming passion for him. Political stubbornness thus did not give him a niche in the egalitarian company of Jawaharlal Nehru and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. He was smitten by the daughter of his Parsi friend and married her. Subsequently, however, he would not countenance the marriage of his daughter with a Parsi man. He severed all links with his daughter. If he suffered inwardly from the consequences of his decision, he showed precious little sign of it.

One cannot ignore the notion that the urbane Jinnah quickly mutated into a haughty Jinnah as the chasm between him and the Congress widened. His conscience was not riled when he encouraged his Muslim League followers to paint Khan Sahib and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan of the North-West Frontier as heretics or closet Hindus standing in the way of Muslim self-determination. His contempt for the scholarly Abul Kalam Azad did not become a man of his background. Prominent Muslim politicians who did not agree with him or toe his line were, for him, beneath contempt. And when Gandhi died, it was pettiness which underlined Jinnah's expression of condolence for the Mahatma. A niggardly statement of sorrow went out from him in January 1948. Incidentally, by that time Pakistani army regulars, in the guise of Tribals, had caused havoc in Kashmir. It was a miscalculation the ramifications of which are yet being felt in the subcontinent.

In 1946, Jinnah tinkered with the Lahore Resolution adopted by the All-India Muslim League in March 1940. He had the operative phrase, 'independent states', in the resolution quietly changed to 'independent state'. He then explained away, without convincing anyone, 'states' as having been a typing error. Six years for a typing error to be noticed and corrected? It was duplicity at work and the ramifications would be severe. Then again, there would be the consequences of his call for a Direct Action Day on 16 August 1946.

The Muslim League did not explain at whom or what the day was aimed. Nevertheless, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Prime Minister of Bengal and a Jinnah loyalist, would cheerfully go into fulfilling his leader's wishes. No fewer than 10,000 Muslims and Hindus perished in communal riots first set off in Calcutta on the day and spacing out over the next few days to bring Noakhali and other places into the conflagration. Jinnah showed no inclination and had no time to visit the riot-torn areas. A shell-shocked India left Gandhi and Nehru scrambling to restore communal peace, a semblance of normalcy in collective life. Jinnah stayed aloof. He knew the killings would force Britain's hand and give him his Pakistan.

In the years leading up to Partition, Jinnah and his acolytes loudly propagated the false notion of Muslims being a nation, as opposed to being a religious community, and therefore deserving a separate country. Ironically, on 11 August 1947, a few days before the emergence of Pakistan, he loftily informed the country's constituent assembly that all religious communities were free to practise their faiths and that the state had nothing to do with that. Pakistan, the argument went, was for everyone irrespective of caste, creed or colour. That was a clear contradiction, a contravention of the politics he had practised thus far. It was akin to his sense of horror when he was informed that the Punjab and Bengal would be partitioned along communal lines. Punjabis and Bengalis, he put it across, had common legacies that could not be sundered. Jinnah was willing to have India sliced into two across a Hindu-Muslim divide, but was uncomfortable when the same standard was applied to a division of the provinces. He did not notice the fallacy of his argument. Or he deliberately ignored it.

In August-September 1947, as Hindus and Sikhs left Pakistan for India and Muslims made their way to Pakistan, with thousands among these three communities perishing in murder and mayhem along the way, Jinnah took a helicopter ride and observed the unprecedented migration from the air. For the first time in his life, as the Pakistani journalist Mazhar Ali Khan was to tell his wife Tahira Mazhar Ali subsequently, Jinnah appeared to realize the macabre nature of the demons Partition had unleashed. 'What have I done?' He asked. Silence was the response, from those around him.

Jinnah, as Bangladesh's Justice Abdur Rahman Chowdhury once told this writer, was blissfully unaware of Bengali culture. When on his visit to Dhaka in March 1948 a group of Bengali students (Chowdhury was among them) called on him to make their views on the need for Bengali to be the state language of Pakistan known to him, Jinnah left the students in a state of incredulity: he wished to know if Bengal could point to any prominent cultural and literary icons as part of its cultural heritage!

A reassessment of Jinnah becomes necessary in the regions of the subcontinent he cobbled into the state of Pakistan. East Pakistan was to fight its way out of Jinnah's state as a secular Bangladesh in 1971. What remains of Pakistan today confronts the murderous Taliban, the sinister Inter-Services Intelligence and periodic foreign drone attacks inside its territory. Its feudal classes keep their grip on politics. And so does the military. Meanwhile, the long twilight struggle for a free Baluchistan, initiated in the 1960s, goes on.