‘ISI didn’t plan the Taliban victory. The US facilitated it,’ says Adrian Levy

Open Conversation with Adrian Levy, author

/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AdrianLevy1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

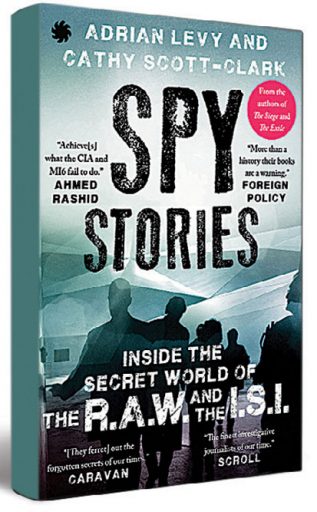

Adrian Levy has never stayed back this long in London since he was 16, he says. The Covid-19 pandemic has confined him to his London home from where he currently gives interviews on the latest among several books he has co-authored with Cathy Scott-Clark who, these days, is tied up with an upcoming project: on the American use of torture. Like their previous works, their new book Spy Stories: Inside the Secret World of the R.A.W. and the I.S.I. is an explosive volume that talks about the men and methods of the bitterly rival external intelligence agencies of India and Pakistan, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) and the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). The 360-page book offers valuable insights into various operations launched apparently by ISI and RAW, the 2019 Pulwama attack, the Pathankot airbase attack of 2016, the Parliament attack and also about people and assets.

There is much more in the book than what has often been said about the two agencies.

The duo, known for their superb investigations, have authored books and made films on jihad, geopolitics, strategy and foreign policy, among others. Their books include The Exile: The Stunning Inside Story of Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda in Flight; The Meadow: The Kashmir Kidnapping That Changed the Face of Modern Terrorism; The Siege: The Attack on the Taj; Deception: Pakistan, the United States and the Global Nuclear Weapons Conspiracy.

In his conversation with Open, Levy dwells on the Afghan situation, the role of spy agencies in that country and warns against knee-jerk reactions on the part of the media and analysts to run into judgments on events, saying these could be profoundly damaging. As with terror attacks, he says it is important to understand the distinction between intelligence failures and the intent to allow things to run their course. Excerpts:

How many years did it take you to finish this book?

It’s a continuum for Cathy and myself. Each book is an overlapping enterprise rather than one book or film ending and another beginning. Work goes on concurrently and so it is more horizontal than vertical. For example, when we were doing The Meadow (the 2012 book about the 1995 kidnapping of tourists in Kashmir by an unnamed group to secure the release of dreaded Pakistani militant Maulana Masood Azhar), we had the idea of the Western hostage-taking in mind to look at the wider issue of disappearances. But we couldn’t do it for many years. Finally, after the earthquake happened in Kashmir (in 2005) and the security came down, we got to see the landscape of Kashmir.

Now, building relationships takes a long time. It is a decades-plus-long effort. Cathy must have worked from 1994 to until now, but in terms of specifics, the work on this started in 2009 when we were doing The Siege (on the 26/11 Mumbai attacks). We had this idea then of making a South Asian version of the Israeli film called The Gatekeepers, which is an intriguing, well-made, educative and entertaining documentary feature that got the Israeli security agency Shin Bet to open up. It gave a conflicting, overlapping narrative of oral history, not substantiated by paperwork, how they (members of Shin Bet who agreed to talk) saw the Israeli-Palestinian issue. We had this idea to make a film in which one of us would be on this side of the LoC and the other on the other side. We started conversations in 2009 with everybody, but on either side, not one person wanted to be on camera (from ISI or RAW).

The issue with spies is that they don’t want to be accountable to anyone. We kept working on it, with new RAW chiefs, new ISI chiefs, telling them to own the narrative. Owning the narrative is what Americans had done exceptionally well. But everyone in India and Pakistan rejected it although we kept pleading. So instead of a film we decided to write an oral book based on inputs from all of those we spoke to about ISI and RAW. We were working on the book intensely for four years, travelling to India and Pakistan. But most of these people who spoke to us were people we knew since 1994.

When did you meet Major Iftikhar whom you describe in the book as the nom de guerre for an ISI operations officer?

We met him three years ago, but everyone else who provides the infrastructure were relationships we began when we were kids (laughs) and so they were genial. A lot of meetings, by the way, happened in the Gulf states, Thailand, a proxy territory for a lot of spy agencies. Some meetings took place in France, Germany, Syria, the US and England. These meetings overlapped with another project that is coming up: on American use of torture. We have an extremely thin level of budgeting and so we manage multiple projects together. Otherwise, it would be practically and economically impossible for two people who do freelance work and are not supported by institutions to do such projects.

Do Iftikhar and Monisha (the RAW agent who is a source for the authors) have multiple identities?

Yes. We keep interviews that go back to 1994. All the interviews are taped and transcribed, but we agreed to use trade names. Iftikhar was one of the identities he (the ISI operative) had used. He had five identities all the way from Korea in 1994 up until his vanishing. In fact, Iftikhar was his favourite nom de guerre. Monisha had several identities. She was not in clandestine service. She was an analyst.

In David Muntaner’s 2015 film CIA vs KGB: Battleground Berlin, CIA officers admit that KGB was slightly superior to them because of their ideological drive and commitment. Is that kind of faith-based passion at play between ISI and RAW?

It is a super-interesting question. I have got many different takes on that. I believe that it is true that both outfits take on a different mantle as the time changes. If you take a micro timeline, that is from 9/11 onwards, you can see that there is an evolution of ideology and character within those organisations. It will be tempting initially and incorrectly to say that India is taking on its ideological foe in ISI, which stands for an austere and extreme interpretation of Islam. That is to assume that RAW doesn’t have any politics. I touch upon this because that (giving such a perception) is one of RAW’s biggest achievements. Its projection of itself as benign and vanilla is something it does very effectively.

Owning the narrative is what Americans had done exceptionally well. But everyone in India and Pakistan rejected it. So instead of a film we decided to write a book based on inputs from all of those we spoke to about ISI and RAW. We were working on the book intensely for four years, travelling to India and Pakistan

Both organisations have gone on interesting journeys. Both involve inculcation by a faith and a certain kind of worldview, a deepening of a religious-social worldview. It is certainly true of RAW and certainly true of ISI. Let’s not forget that a new kind of nationalism is emerging in India encouraged by the US post-2001. Therefore, the forces that become corrosive in Pakistan become corrosive in India, too. And yet the story is not told that way. You have jealousies on both sides.

Your book quotes Monisha saying that Lodhi Road (RAW headquarters) is dominated by IPS officers who think Muslims are duplicitous. How do you think such an attitude would restrict intel gathering against ISI?

I am not in the business of writing a transformative policy document. I am reporting (laughs). I will make an observation though. India’s Intelligence Bureau (the main internal intelligence agency), for example, has a certain number of Muslims but senior positions are mostly not filled by them with the probable exception of Asif Ibrahim. The organisation, according to insiders—and it is not my view—suffered incalculably because of that. If you look at all spy organisations across the world, they invest a lot in communities they investigate. In that sense, the transformation of the CIA, MI5, MI6 is all radical. In places like India, such reforms are only on paper.

The result of this attitude could be dangerous. Again, it is very easy to look at everything through the narrow prism of post-2014 politics when BJP returned to power. Actually, it involves a much longer timeline, all the way through various other governments. RAW officers tell you that the organisation does not reflect the humongous gifted communities of India and that it would benefit from being a truly representative security establishment.

Who do you think are the most effective, storied and feared officers of RAW and ISI?

It would be true to say much against the common beliefs that RAW and ISI have both been hugely effective. And yet, because they resist telling stories, what you tend to hear is hugely negative, such as big episodes of infiltration, collapses, the failures like 26/11, etcetera. There are many, many heroes. At a very senior level, I always found that (the late RAW chief) B Raman’s influence just cannot be overstated. He is an extraordinary person who brought in extraordinary changes, professionalism and rigour to RAW.

KC Verma is among such a breed of people who did the impossible, politically as well. A very good example of short-termism is that after 26/11 lots of people said to me that we never imagined the unimaginable. That’s just rubbish, right? What do the security services do? They imagine the unimaginable every day. People like Verma and Raman imagine the unimaginable and try to go into the unimaginable space, including the outreach to Iran, the outreach to China, the balancing of America, Iran and China, the outreach to Russia and so on. They played hugely sophisticated, big-country games that are never really well-documented. The courting of Israel is a story in its own right.

The illicit relationship with Israel, which took place in the 1990s at a time when it couldn’t even be acknowledged, goes right up to Pegasus today. So, I’ve named some of those people. Anyone who is really interested in this psychology of jihad, who is really interested in the pathology of political movements, wants to be with these people. You want to understand how and what are the influences that lead to the cell splitting, the creation of new ideologies and flavours. There is an enormous knowledge base in RAW and it is never shared with its own people.

What do you think is the role of ISI in the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan?

I think there are some useful handholds: in November 2001, ISI under General Ehsan ul Haq manoeuvred Saudi royals to front a deal to protect the Taliban and that was backed by the Tony Blair government, in parts, in the UK. They warned—collectively—that the movement could not be defeated and should be incorporated into what the US intended to do in Afghanistan.

That proposal was taken by the Saudi royal family and Blair to Dick Cheney who rejected it outright—just as he rejected a side deal with Iran which in 2002 and 2003 offered the bin Laden family and top military commanders in their custody, in return for normalisation of relations with the US. Cheney said then that Iran would fall after Iraq and the Taliban, and the US was not prepared for any deals or normalcy as it invaded Baghdad.

The Taliban victory is inspirational for Islamists, Islamic states but also for anti-imperialists. Taliban are not Al Qaeda. I fear the chaos more than the Taliban. In ungoverned spaces, terror groups could grow as happened in Libya and Syria. So, there’s an argument to help the Taliban quickly govern and increase their capacity

That deal was never forgotten by ISI—and Ehsan’s legacy would live on until 2006-07, when ISI and CIA parted ways, the relationship having soured completelyas ISI would not relinquish the idea. For its part, the US—by now distracted by civil war in Iraq—would not embrace it and could not persuade Pakistan to relinquish its strategic interests.

What we see here is not so much Pakistan’s manifest destiny or even long-haul planning but the abject failure of US policy to launch an impossible low-intensity war in Afghanistan, and then further dilute it with an illegal invasion of Iraq—and finally abandoning both Iraq and Afghanistan, while neighbours in Pakistan continued to hold on to their ambitions.

Imagine if Bush-Cheney had embraced the Saudi-Pak plan at the start and also taken control of the bin Laden family and Al Qaeda military commanders. How many lives would have been preserved? Impossible to know, but a painful thought.

ISI did not plan this victory. And what we are seeing is not the fall of Saigon. It is the failure of Kabul to rule all of Afghanistan, and for a centralised army to represent an ethnocentric nation. Kabul did not equal Afghanistan, ever. Taliban prevailed because the governors of provinces decided not to oppose them, and not to support corruption in Kabul, rather than acceding to the Taliban or their goals and ideals. Provincial governments voted against Kabul and enabled it to be encircled and occupied today. ISI did not do this. The US facilitated it.

How influential do you think RAW is in the Panjshir Valley, the seat of anti-Taliban resistance in Afghanistan?

ISI was attempting to make outreach here—but stumbled over the fact that a corps of officers, all forged in the 1980s war against the Soviets, held sway over Afghan policy. RAW was doing the same, and had contacts but inside the Panjshir Valley there seems to have been a feeling that these links would not amount to anything substantial—in terms of political capital, actual capital or mentoring.

If you look at spy organisations across the world, they invest a lot in communities they investigate. In that sense, the transformation of the CIA, MI5, MI6 is radical. In India, such reforms are only on paper. The result could be dangerous. RAW officers tell you that the organisation would benefit from being a truly representative security establishment

The outcome in Kabul is extraordinary—mostly for what it tells us about the US. The campaign to rout Al Qaeda became a war against the Taliban who were not responsible for 9/11. Seeking vengeance, the US lost its way and—instead of reassuring a terrified world post-9/11 and selling the idea of secular democracy—has worked to undo rules-bound systems.

Talibs are from Afghanistan and have regained power in their country upturning a meandering American project. They are not a terrorist movement but a group with stringent precepts and beliefs. So, let’s wait to see what they have become and what they want to achieve. Previously they have not sought influence or power outside Afghanistan. India, for example, was not their enemy. What is also unknown is what their attitude will be to the foreign radical elements in the country—the Islamic State, Al Qaeda, Pakistan Taliban, and Sunni fighters from Iran and China. Will they continue to win shelter? Will they be allowed to recoup and strike from Afghanistan?

The Taliban victory is, of course, inspirational—for Islamists, Islamic states but also for anti-imperialists. But will it grow movements inside the country or inspire others elsewhere? We don’t know is the short answer. Taliban are not Al Qaeda. There was a fraternal relationship, mentoring by Al Qaeda. And Taliban leaders have been ambiguous in their statements. I fear the chaos more than the Taliban. In ungoverned spaces, terror groups could grow as happened in Libya and Syria. So, there’s an argument to help the Taliban quickly govern and increase their capacity. More government and greater authority rather than a lawless vacuum are preferable.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba