If This is a Man

ULRICH ALEXANDER BOSCHWITZ was returning from exile to join his mother in England when his ship MV Abosso was torpedoed by a German submarine, killing all the 362 passengers aboard. The enemy finally caught up with the 27-year-old novelist. Recently he had written to his mother about revising his second novel, originally written in German, published under a pseudonym three years earlier, in 1939, in England as The Man Who Took Trains. Reviewers largely ignored it then. His mother would never receive the reworked version he had promised. The original would get a second life more than seven decades after the death of Boschwitz, who, like his protagonist, was a passenger for whom what mattered most in the end was not a destination but the false freedom of perpetual movement.

Boschwitz, born to a Jewish father and a Protestant mother in Berlin in 1915, began to run for his life when he was 20. The Nuremberg Laws, just enacted by the Reichstag, made him a marked man in Nazi Germany. He and his mother first went to Sweden, where he wrote his first novel, People Parallel to Life, and, after seeking home across Europe, he would finally find one in England. It was 1939, and the shards of Kristallnacht, the Night of Broken Glass on a November night in 1938 when storm troopers hunted down the Jews, heralding the Final Solution, still lingered in his memory. He wrote The Passenger in four weeks. As an “enemy alien”, Boschwitz, along with other German refugees, would be deported to a prison camp in Australia, a British dominion. When he boarded MV Abosso, he was free as a “friendly alien”, but freedom was in the cruel depths of the Atlantic.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

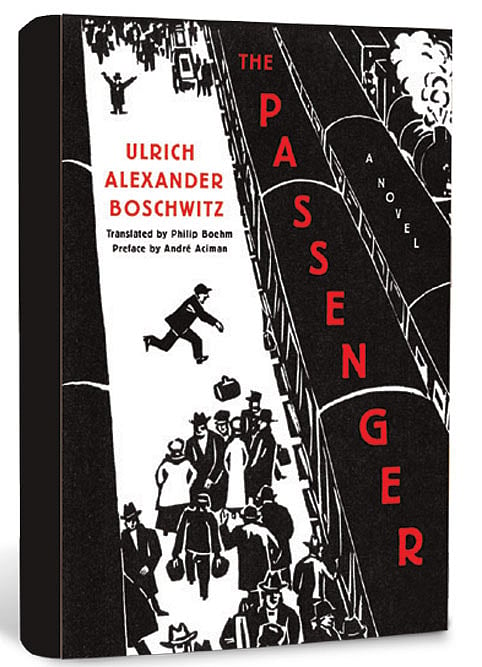

The performance state at its peak

The Passenger owes its second life to the excavator of literary fiction, Peter Graf, who, with the help of the novelist’s niece, retrieved the original typescript of the novel from an archive in Frankfurt. “I really believe there is something in the book, which may make it a success,” Boschwitz had written to his mother, telling her how a revision by an experienced hand would enhance the work. Graf would become the German editor of a raw imagination rooted in the dehumanisation of power. Published in Germany three years ago, and now translated into English by Philip Boehm, The Passenger (Metropolitan Books, 266 pages, $24.99) shows, as all great novels born of the pathologies of hate do, how art alone can redeem history.

In the first pages of The Passenger, we meet Otto Silbermann, a successful Jewish businessman whose company is headed by his German friend and partner. Being a Jew, though he doesn’t look like one but his passport is marked and his name is a giveaway, he cannot helm his own business. In choreographed irony, the novel opens in a Berlin railway station, where Silbermann is seeing off his partner on an important business trip. That is the prologue to a betrayal—and to the slow process of losing one’s humanity. When the scene shifts to the drawing room of his apartment, the betrayal becomes a theatre of the isolated. A German swindler, under the guise of empathy and friendship, wants to steal his home; Silbermann’s son, living in Paris, calls him to say that there is no chance of getting a visa for him and his wife, an Aryan, immediately. Then comes the violent knock on the front door.

It’s the Berlin of Kristallnacht, or the November Pogrom, of 1938, when Hitler’s civilian militia was out on the street, vandalising Jewish property and terrorising the racially impure. Silbermann, wealthy and honourable, never saw himself as an outsider, until the Aryan marked him as one. Even as his life was shielded for a few tentative moments by the front door, he was in no mood to give in. A German and a war veteran, a patriot and a hard worker—he was entitled to his home, his freedom, his wealth, and his rights. He still refused to believe that he was naïve in his self-assessment as a Jew in the Third Reich.

“Everything’s happening so quickly,” he thought as he began his life as a lone passenger in an alien country, “they have declared war on me, on me personally. That’s what it is. War has just been declared on me once and for all and right now I’m completely on my own—in enemy territory.” He’s setting himself apart as a condemned adventurer in history’s worst picaresque.

Soliloquising and moralising, and still burning with righteous rage, he becomes a permanent passenger of the Reichsbahn; he begins by choosing the destination, but it won’t be long before the destinations start choosing him.

It’s a journey semaphored by farce and absurdity, customised cruelty and accidental kindness, and the traveller, as he shuttles between railway cabins and hotel rooms, between telephone booths and restaurants, between the fleeting comfort of movement and the dread of stillness, realises that he has not just lost an entire world. He has lost the identity of the person he thought he was. He was buying tickets to someplace where he could regain his humanity.

Along the way, in his encounters with fellow passengers, some luckier, some as doomed as he was, he realises to his dismay that his “fate has become a figure of speech.” He is not the perfect fugitive either. He could be arrogant and superior, selfish and foolish, fearless and even flirtatious; the one constant in the relentlessness of his train hopping is the severity with which he clings to a moral system as a man who won’t so easily send his honour to a concentration camp. He could be tentative in a moment of erotic possibilities, but he is fiercely adamant, risking his life, when he is ignored and his rights are brushed aside. When he reaches a police station to report the theft of his briefcase with thirty thousand marks, he is not taken seriously, and threatened with arrest. Still he dares “because I no longer care what happens to me. Because I have dutifully paid my taxes year after year and now I’m requesting that the police also fulfil their duty to me as a citizen.” He is still asking for the small decencies of being human.

And that is what was denied to people like Silbermann by the cult of the pure race. In the individual sorrow and desperation of a Jew travelling in a walled space of psychedelic horrors, Boschwitz, himself a tragic passenger, saw the larger story of the abandoned. Writers like Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel told the story through their own survivor sagas in death chambers built for them by the Führer. Boschwitz, raw and surreal, turns the existential drama of history’s most enduring outsider into a testament of the victim who won’t go away even after the Führer’s exit, even after the last cattle wagon had left the station. We read Boschwitz today, in fiction’s most rewarding second coming, with the painful realisation that somewhere in this world the passenger is still queuing up for a ticket to the safest destination that doesn’t exist.