Beyond the Noise of Dharma

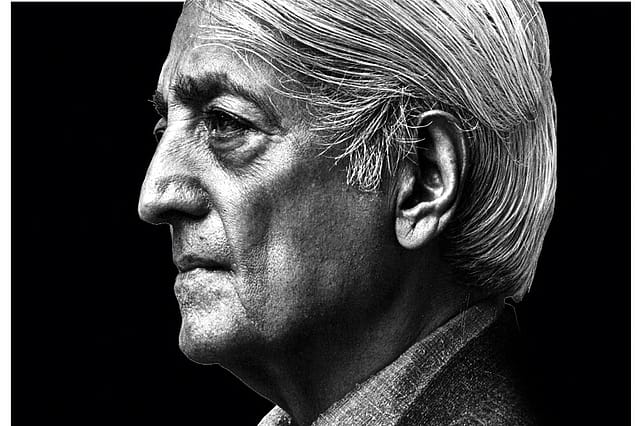

NOVEMBER 18TH, 1985. In one of his last talks at Rajghat, Varanasi, J Krishnamurti declared "Whatever you think, you are."

Krishnaji, as his friends called him, was just over 90 years and six months. This would be his last trip to India.

In the video of the talk he looks happy, even radiant. But soon afterwards, he would suffer a setback. Fever, exhaustion and weight loss. He would decide to travel back to the US.

On January 10th, 1986, he embarked on his last journey. Over 24 hours, from Varanasi to Los Angeles.He had already been diagnosed with terminal cancer.Now he wanted to spend his last days at his retreat in the Ojai, southern California.

There he passed away on February 17th, 1986.

When I visited Rajghat last week, I felt so clearly the truth of "whatever you think, you are". Indeed, that was what the Dhammapada had also said long, long back:

Manopubbaṅgamā dhammā manoseṭṭhā manomayā/ Manasā

ce paduṭṭhena bhāsati vā karoti vā/ Tato naṃ dukkhamanveti

cakkaṃ'va vahato padaṃ.

All that we are is the result of what we have thought: it is founded on our thoughts, it is made up of our thoughts. If a man speaks or acts with an evil thought, pain follows him, as the wheel follows the foot of the ox that draws the carriage.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

In my case, to put it rather plainly, my mind was too much with the world.

I realised that I had inverted Wordsworth's famous lines: 'The world is too much with us; late and soon,/ Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers."

The incessant travel, speaking engagements, meeting and talking to people…. In addition, of course, to my main administrative responsibilities. Also the punishing writing schedules. What was it all for?

Entering the Krishnamurti Foundation of India (KFI) compound, just across from the Rajghat School and adjacent to the Vasanta College for Women, provided the much-needed reality check.

The stillness and simplicity of the campus by the river afforded the space needed to clear the mind of its baggage. To be cleansed of the burden of the past, of centuries of conditioning, was a precondition for it to be free.

Only an ageless, open mind could apprehend reality. Both its beauty and totality.

We arrived late at night, in the darkness, through the dusty and crowded Benares streets. Rajghat is literally at one end of the city, with Adikeshav Ghat just under the walls of campus.

I was reminded of the almost surreal arrival of Raja Rao at the same location in the opening chapter of On the Ganga Ghat: 'In Benares everything—bullock carts, rags, human excreta (in cones or flat), fallen wayside hay, tree-tops, burnt charcoals, abandoned bus horns, beggars, ugly names on worn walls (maybe of politicians)—everything, everything benefits from all acts—for no act here has any consequence. An action must have cause and effect. In Benares there seems no reason for a cause, thus the result is, no effect. No act breeds an act. And so eternity, the bent meaning of the river.

But night, the all pervading immemoriality that the earth gives herself for her cogitations, it too was an observant of this haggle.'

Just the previous evening, on the eve of Vasant Panchami, we had witnessed the Ganga aarati in a boat that wafted down the river. The lit-up ghats had a timeless quality to them.

But they were all of them relatively new, mostly rebuilt by the Marathas. After Aurangzeb had practically destroyed the city, along with its holiest of holies, the Vishwanath Mandir itself.

As a visitor for several years, I knew that the ghats and the city were cleaner than ever. After Varanasi had become Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Lok Sabha constituency, there was also a brand new, multilane highway to the airport.

Despite the newness, one thing had never changed. The ceaseless funeral pyres. Burning day and night without respite. Almost since the beginning of human habitation in the world's oldest city.

We passed them too, on Harishchandra and Manikarnika ghats. Only in Kashi, the city of light, did life and death live in such stark and startling proximity.

The best food, music, flavours, perfumes, textiles, wrestlers—and, in the past, dancing girls and ta'waifs. All the joys and temptations of the flesh cheek by jowl with the presence of death.

And how brightly does flesh burn, whether in life or death.

The next morning, we arose early to go to Kashi Vishwanath. We were fortunate to get a police escort. Having some extra help was wonderful. Even to have a glimpse of the lord of the universe.

This version of the temple was rebuilt by Ahalyabai Holkar in 1780. The Maharani of Indore, a visionary leader, great administrator, was also a wonderfully pious and enlightened lady. She lost her husband, but rising above the stigma of widowhood, ruled her kingdom benevolently and efficiently. The golden plating on the shikhara or temple tower was donated by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1835.

Right next to the temple, in fact on top of its ruins and growing out of it, is the Jama Masjid. This central mosque of Varanasi, it is better known as Gyanvapi, after the temple that Aurangzeb destroyed in 1669. The Nandi is still facing that structure to indicate where the Shivalinga originally was.

The mosque is a spectral presence, painted white, completely barricaded, with tall steel fences and barbed wire. Though protected by an armed constabulary at state expense, the disputed structure wears a deserted look. The vandalism of history and the illogic of a secular state stare us in the face.

More so because of the incessant if not incendiary 'dharmic noise' all about us.

The shrillness of the appeals made in the name of religion. Mostly political and polarising, they are so much a part of India's current landscape.

We need a Krishnamurti to challenge us, to wake us up from the hypnotism of religious and political sloganeering. Truth is a pathless land, he had famously declared, when he walked away from the Order of the Star. The huge, worldwide organisation had been set up to promote him as the World Teacher, the Maitreya Buddha incarnate.

But he found it all much of an obstacle. So much propaganda, with a complex hierarchy of Masters and a new church of sorts. He broke away, rejecting the messianic mantle, the fame and the glory. Also the authority and the organisation. He was only interested in setting us free. Unconditionally free.

But organisations are, after all, necessary. Else, why would he have established schools all over the world? And branches of KFI in various parts of India, as well as their equivalents abroad?

In the broad daylight, we saw a kite swoop down to the river, superbly, even delicately, picking out its prey from just below the surface of the waters. From across the river, loudspeakers blared the minute by minute progress of a large Saraswati Puja.

No part of inhabited India was free of invasive and violating sound. Mostly in the name of one religion or the other. Nowhere could one be quiet or contemplative, except within oneself.

Why are we Indians so afraid of silence?

I was convinced in my meditation in Krishnamurti's room, now the silence room, that dharma needed to be simplified. Shorn of its clutter. Politics was the quest for power, quite different in its operations from one's commitment to liberate oneself from guilt, suffering, fear and ultimately, death.

In his very last lecture at Rajghat, recorded on November 19th, 1985, Krishnaji had summed up the urgency of transformation so well. "All time is contained now." We had to act now.

In the meanwhile, our Prime Minister was doing a fabulous job of restoring Varanasi to a portion of its faded glory. From beneath the rubble, 56 temples were emerging in the corridor he was making from the Vishwanath Mandir to the river.

Ab taq chappan, I thought. More to come.