Apropos of Tablighi

TOWARDS THE END of Fyodor Dostoevsky's masterpiece Crime and Punishment (1866), Rodin Romanovich Raskolnikov, the tortured and guilt-ridden protagonist, has a strange dream.

Haunted almost to the verge of paranoia and madness, he is at last close to repentance. Feverish and ill, he rues his improvident murder of the old pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna, and the even more monstrous, impetuous killing of her meek, innocent, physically challenged sister, Lizaveta.

Slipping into disturbed sleep, Raskolnikov, tormented and delirious, dreams of a global pandemic. No specific illness is mentioned but the whole world is infected.

The contagion has, almost prophetically, come from the East, from the 'depths of Asia'. No one quite understands the microbe that causes it, but it blights not so much the bodies but the brains of its victims. The infected begin to believe that they alone possess the truth. They think they are infallible, suspecting others of evil and immorality.

The disease makes the sufferers wrathful and violent. People kill each other out of a pointless and malevolent madness: 'Everyone was to be destroyed except a few chosen ones. Some sort of new microbe was attacking people's bodies, but these microbes were endowed with intelligence and will. Men attacked by them became instantly furious and mad. But never had men considered themselves so intellectual and so completely in possession of the truth as these sufferers, never had they considered their decisions, their scientific conclusions, their moral convictions so infallible. Whole villages, whole towns and peoples were driven mad by the infection. Everyone was excited and did not understand one another. Each thought that he alone had the truth and was wretched looking at the others, beat himself on the breast, wept, and wrung his hands. They did not know how to judge and could not agree what to consider evil and what good; they did not know who to blame, who to justify. Men killed each other in a sort of senseless spite' (Crime and Punishment, tr Constance Garnet, 1914, revised by Juliya Salkovskaya and Nicholas Rice, 2007).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

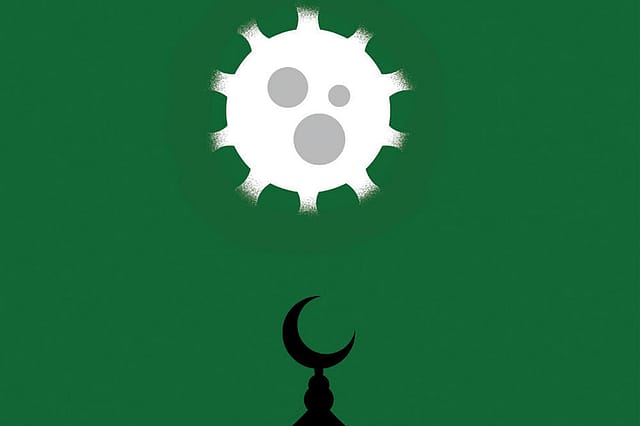

Today, the senseless and inconsiderate actions of the Muslim group Tablighi Jamaat (Outreach Congregation) as well the rage, anger and incomprehension of the populace directed at them resembles somewhat this sort of panic and pandemonium.

During a police probe it was revealed that some 3,000 people, including foreigners from Indonesia, Jordan, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, China, Ukraine, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Bangladesh were at the Markaz near Nizamuddin in Delhi. Even after the lockdown on March 24th, over 1,500, including 200 foreign nationals, remained at the venue.

The overthrowing of the social and moral order almost is the consequence. Fury on social media and hatred widespread. Restraints and civilities disabled or kept in abeyance. Perpetrators and victims brought down to the same level.

The state's violence and callousness against the exodus of helpless migrants fleeing the contagion and the metropolis to return to the longed-for security and safety of their distant village homes. And callous carelessness of religious zealots turned corona superspreaders.

Both have spiked a moral outrage rendering us equally impotent as hopeless.

Yet each of us, not excluding the sometimes conflicted and contradictory political, medical or financial experts, considers himself or herself to possess the truth. As Dostoevsky puts it, 'Each thought that he alone had the truth and looked with contempt at the others.'

Certainly, it would seem that the controversial head of the Tablighi Jamaat in India, Maulana Saad Kandhalvi, thought so when he exhorted his partly infected flock to disdain social distance because it was a way to divide Muslims.

It was better to die in a mosque, he was reported as saying, than anywhere else: "They are trying to stop and divide us… asking us not to gather, they're trying to scare us by saying we will get infected… . This restriction is placed to stop Muslims from joining hands using a virus."

The Tablighi followers had been expressly admonished against congregating by the Delhi police, the warning purposefully and perspicaciously recorded on video. Yet, that did not prove to be sufficient to disperse them.

Not only did the gathering continue beyond the lockdown of March 24th, with dozens of foreigners in the large, illegal gathering. Worse, several of the infected travelled to other parts of the country, extending the virus to hundreds of others.

While attempts are being made to trace these infectors, their leader, Maulana Saad, is, apparently, under self-quarantine, but has not been arrested. Sadly, however, several of his followers have already died from the dreaded virus.

Saad is the head of one of Tablighi Jamaat's factions. His grandfather, Muhammad Ilyas Kandhlawi, founded the Islamic evangelist movement in Mewat in 1925. That is how the Meos, among whom he lived and preached, were supposedly purged and purified from their Hindu-like habits and practices.

Ironically, though Ilyas studied at Darul Uloom Deoband, his grandson Saad has been accused of deviation and apostasy by the same institution. In a fatwa issued a few years back, the decree by the seminaryobserved, 'We can't remain silent and a mute spectator when Maulana Saad Kandhalvi continues to disseminate his perverted views and wrong interpretations about Islam in large gatherings… . After a close analysis of his speeches we have come to the conclusion that Mualana Saad Kandhalvi has gone astray and he must repent without any delay' ('Tablighi Jamaat India head has gone astray, must repent: Darul Uloom Deoband', December 8th, Ummid.com).

In India, the Jamaat, though proselytising, has been mostly below the radar, attracting little attention. Certainly ordinary Indians know little about them. That is because its practitioners concentrate on purifying the believers, the already converted, rather than attracting new adherents.

They want to take contemporary Islam, including in matters of dress, eating and social arrangements, back to the days of the Prophet Mohammad, the founder of the faith. Their revivalism goes, some would say, to absurd extents, including eschewing all modern conveniences, such as toothbrushes, beds and dining tables, in favour of a rigidly simple way of life.

The Jamaat itself prefers to be secretive about its practices and beliefs, even avoiding bank accounts and written documents to escape scrutiny and detection. Similarly, Tablighis shun the glare of media and publicity.

But they constitute a huge and powerful organisation, spread across dozens of countries all over the world, and with a following estimated to be close to 100 million. In fact, just across the border, in Pakistan, the Jamaat has many influential and powerful members, including its former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, former President Muhammad Rafique Tarar and former chief of the Inter-Services Intelligence Javed Nasir.

Though apparently non-confrontational, even quietist and law-abiding, the Jamaat is considered to foster more dangerous elements. The Tabligh is have been attacked for not being orthodox or radical enough by some, and being soft jihadis and dangerous sympathisers of extremism by others. In the UK and elsewhere, several jihadis started out as Tablighi recruits before getting further radicalised.

Nothing short of a 'planned conquest of the world' is their ultimate aim, according to Marc Gaborieau, a French expert on the movement ('Transnational Islamic Movements: Tablighi Jamaat in Politics', ISIM Newsletter, July 1999, p 21).

Indeed, there is little to distinguish their core beliefs and ideology from the staunch Sunni Wahabists. Thus, closer home, it is suspected that Maulana Umarji, a Tablighi leader, had a hand in the burning of the karsevaks in the Godhra train tragedy (India Today, February 24th, 2003).

What do we do? The answer, it seems, is simple. It is science, not ideology, that will save us from religious contagion. The irrationality and inconsideration of the Tablighis have already attracted widespread condemnation.

Hindu reaction to Islamic extremism will meet the same fate eventually. For, in the modern world, it is the fate of religion to be defeated by science.

Covid-19, certainly, has shown itself agnostic, if not truly secular. It infects all of us, irrespective of religion, race, nation or community.