An English Sense of Ending

IT'S THAT RARE moment in theatre when the performer becomes the entire performance. Mark Rylance is that performer in Jerusalem, which, running at the Apollo Theatre in London's West End, continues to draw critical superlatives. They say English theatre has not seen anything of this sort, a cultural implosion featuring a great actor defying the limits of the stage as he lobs at the awestruck audience a few uncomfortable questions about the legends of being English, about being trapped inside the psychedelic mythology of the last outsider. If it takes drugged vagabonds and dazed dreamers and a larger-than-his-biological-size fabulist in rags to restore the lost identity of a nation suffering from a loss of its nativist memories, then Jerusalem is one of those boldest alternatives only art can offer. For 160 minutes last Saturday afternoon, I was elsewhere, and London seemed a faraway anomaly with a backstory that doesn't give a damn about the correctness and courtesies of cosmopolitanism. Jerusalem is not nostalgia. Maybe it's a necessary cultural trance.

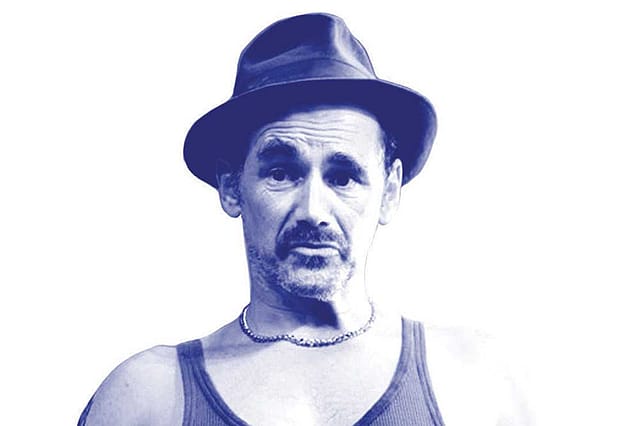

The curtain rises to a rave with screaming music, a whirl of human bodies. The next is the set that doesn't change: a caravan, a discarded wagon with Waterloo written on it; trees looming over desolation; a water tank; torn sofas and other rubbish and accoutrements that befit the homeless at home, in the backdrop of a brick wall that marks the cultural divide—separating the relic from the real. This is the sovereign space of Johnny "Rooster" Byron, played by Rylance, a fumbling, limping, mocking storyteller who mixes humour with pathos, stoicism with sarcasm, and most searingly, rebellion with the stimulant of reveries. He is the patron saint of the abandoned and the loneliest; he is the corruptor redeemer, making his own moral system from the strands of what the authority, which stands for order, thinks are immoralities. He has been served eviction notice, and he turns the crime of encroachment into the native's badge of honour. As the state, the enforcer of modernity, closes in, he takes refuge in stories. It's the mythmaker's rejoinder to bland power. Through the modulation of his voice and the contortions of his every sinew, Rylance makes Rooster the last man standing up to the banalities of the enforcement state.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Since we are in the age of over-contextualisation, Jez Butterworth's play, directed by Ian Rickson, originally staged in 2009, is today seen through the prism of Brexit. And we see it in an England where its current Conservative government, headed by the disgraced Brexiteer-in-chief, is being accused by the winners of the 2016 referendum of betraying the covenant. Boris Johnson's own redemption, despite his bravado amidst life-threatening political chaos, depends on how he succeeds in breaking his inner Conservative free. After narrowly surviving the parliamentary coup by his party members and losing two by-elections and the party boss leaving the sinking ship, he is still so sure of leading Britain through the next decade, and his chutzpah, all said, is the kind of Englishness more engrossing than all the shame-signalling going on in British politics now. Is Johnny Rooster Byron, from his shambolic-bucolic existence as rebel and raconteur, calling out to the lost Brexiteers? William Blake provides the lines, and the title:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon Englands mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant land.

Blake gives the epitaph and an elegy. And in the end the play rises above the context as a tragedy, elementally human, as Byron, as father, lover, and solitary reaper of ancient sorrows, falls on his own oversized mythology. Rylance, in the tradition of English stage giants like Laurence Olivier and Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, elevates the eccentricity and isolation of Byron to Shakespearean heights. Brexiteers in the political theatre are lesser characters.

THE QUEEN, AT 96, remains the ultimate Englishness that doesn't require any overdramatisation to exude power and monarchical stability. The Prince, at 73, remains the tentative future of the monarchy whose institutional worth, it seems, depends on how many millions in cash can be carried in suitcases and Fortnum & Mason bags. The alleged unaccounted donations by a Qatari sheikh to the Prince's charity—Qatar is reportedly London's biggest real estate owner, Harrods and The Shard being the glitziest examples—have reactivated an old conversation in London: Can Prince Charles carry forward his mother's stellar legacy? Or will Arabian knights be the power behind the throne without mystique? The prince is famously unafraid of speaking his mind or tolerating all the barbs from the embarrassed political class. Looks like the public dissident in private has done only what the politicians are capable of doing. A very common prince indeed.

TALKING ABOUT ENGLISHNESS, no matter what definition Prince Charles provides, it is dying a slow death in Albion, and the rogue doctors of mercy killing are to be found in academia. Sheffield Hallam University has suspended the English literature course. Two others have come to the conclusion that arts and humanities are useless. Universities are for producing skilled workers for the job market, not for churning out unemployable eggheads, and resources can't be wasted on poets and philosophers—that's the new socialist campus model. One columnist in The Times, so rightly, called it "cultural vandalism". Once, a great Russian novelist said "beauty shall save the world". Beauty as in imagination. Potential makers of the closed English mind are saying this with a straight face: Shakespeare is full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.