The Dark Web

Perils of social media and technology make it to the big screen

Mohini Chaudhuri

Mohini Chaudhuri

Mohini Chaudhuri

Mohini Chaudhuri

|

25 Oct, 2024

|

25 Oct, 2024

/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/CTRL2.jpg)

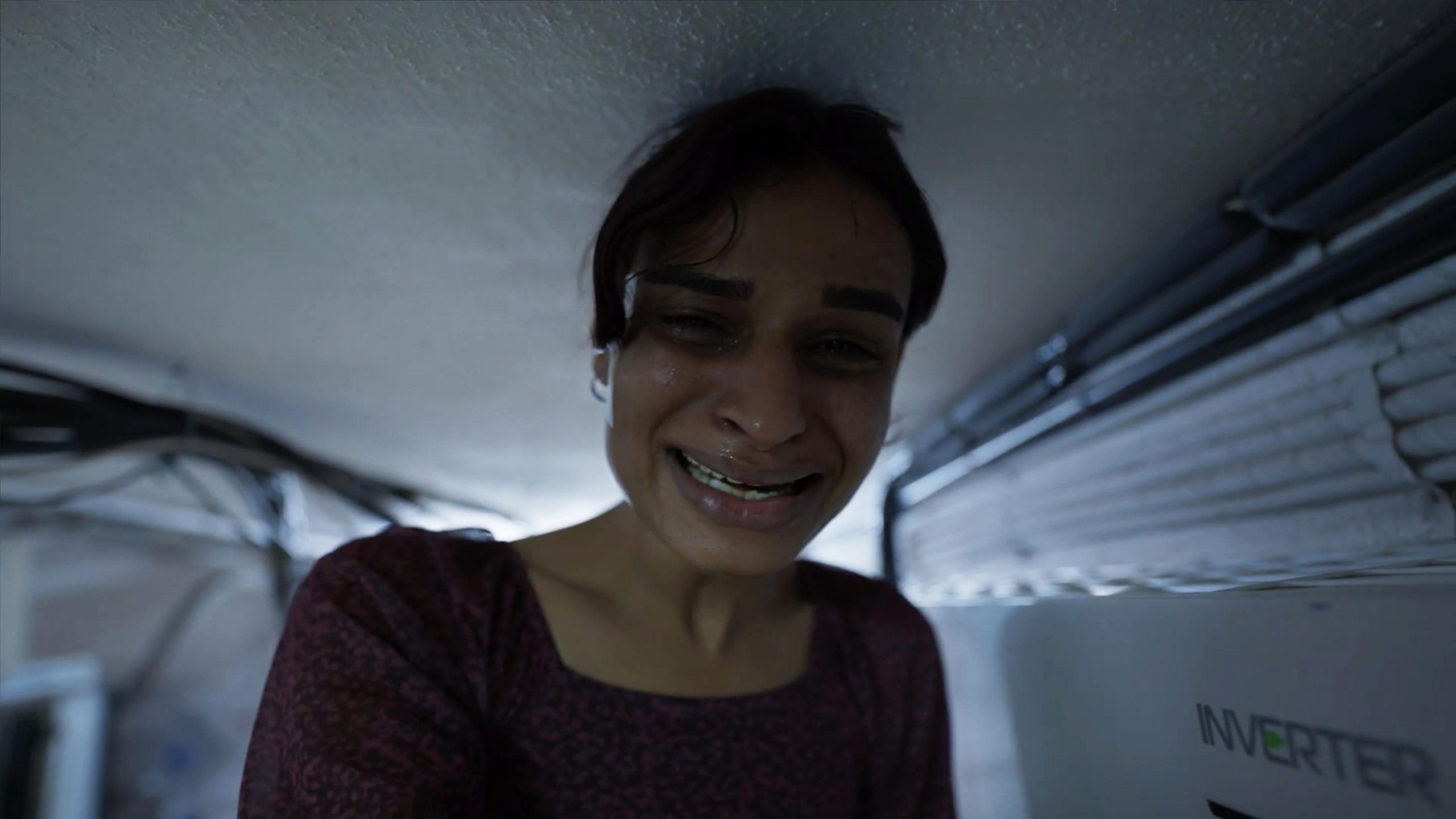

A scene from CTRL (Control)

Earlier this month, Amazon Prime Video released their reality show The Tribe that centres around five Mumbai-based women influencers who are asked to pack their bags and move into a fancy home in Los Angeles to ‘live their best lives’. The assignment is simple. They must churn out regular social media content about their aspirational lives. The fun parties, fancy holidays, the high fashion and details about their relationships—everything is grist for the mill. On the same day, Netflix released CTRL (Control), a film by Vikramaditya Motwane, that also has an influencer called Nella (played by Ananya Panday) as its protagonist. Nella, though fictional, could easily have been one of the girls on The Tribe. Like them, she’s a popular influencer who runs a YouTube channel with her college boyfriend. The young couple are rolling in brand deals and are also living their best lives by monetising every second of their seemingly perfect relationship.

CTRL, however, is a cyber thriller meant to make us take a hard look at our toxic relationship with technology. So while the girls on The Tribe end up on a billboard in Hollywood, Motwane turns Nella’s life into a cautionary tale by putting her through one horror after the other. Hindi films have only recently started asking tough questions about the darker aspects of Instagram culture, the implications of Artificial Intelligence and how it has changed the way we live. Films like CTRL, Dibakar Banerjee’s LSD2 and Arjun Varain Singh’s Kho Gaye Hum Kahan have taken steps in exploring these hot topics that are relevant to our everyday lives.

In fact, through Ananya Panday’s career one can trace the gradual evolution of how this theme has been addressed in our stories. In Liger (2022), she plays a self-absorbed influencer with a phone who mindlessly throws around buzzwords like ‘selfies’, ‘hashtag’ and ‘followers’. In 2023’s Kho Gaye Hum Kahan she is a high achieving MBA grad who struggles with self-worth issues after being dumped by her boyfriend. She seeks social media validation to deal with her loneliness and heartbreak. This year we saw her as a rich Delhi socialite turned journalist in Call Me Bae who breaks a major story on a national telecom company that’s snooping on its customers. And more recently in CTRL, we see her alone in an apartment talking to her only trusted friend Allen, an AI bot that is privy to her deepest secrets. Reality hits her hard when she becomes the victim of a sinister data mining project by a powerful corporation.

While Indian storytellers are just about dipping their toes into the subject, the West has been mining it for over a decade by skilfully using popular genres like horror, thrillers and science fiction to make chilling statements about the threat of technology. Some indie films have picked premises that are wild and dystopian. The 2014 thriller Unfriended speaks about the very real danger of cyberbullying by creating a preposterous scenario. A Skype call between five pals turns unexpectedly bloody when the ghost of a friend who had died by suicide enters the chat. The 2017 slasher film Tragedy Girls dials up the absurdity even further. It gives us two teenage crime reporters who are so desperate to improve their social media following that they begin murdering people to generate more exciting content.

“Then Chat GPT launched, and suddenly everything was becoming very real. There were larger conversations around big tech. Is it the enemy? How do we regulate it?,” says Avinash Sampath, cowriter, CTRL

The widely watched sci-fi Netflix show Black Mirror plays with our emotions in a similar way. Over six seasons, the creators construct bleak and depressing worlds ruined by advanced technology. Interestingly, some of the far-fetched predictions made in the earlier seasons of the show have begun to come true. Screenwriter Avinash Sampath, who co-wrote CTRL with Motwane, points out that one of the tricky parts of writing an effective cyber thriller is keeping pace with evolving technology in the real world.

In 2020, when he began working on the story of CTRL, the conversation around AI was relatively muted. The paranoia hadn’t set in. “All we knew about AI was that it’s one of the most expensive pieces of technology. And given the jugaad mentality of India, I thought we could show that people think they’re using an AI tool, but at the backend there’s an actual group of unemployed software engineers sitting in basements doing the search for you,” says Sampath. In fact, in the initial drafts of the film, Nella has an online stalker, and in a more classic thriller style, she chases him down in person. “For a good few years we thought that Nella was going to triumph. But then Chat GPT launched, and suddenly everything was becoming very real. There were larger conversations around big tech. Is it the enemy? How do we regulate it? At this point, it was hugely unrealistic to show Nella go up against big tech and succeed,” adds Sampath. The last frames of CTRL cut deep. Nella’s attempts to expose a corrupt tech founder have failed. She is alone, friendless and defeated. Out of desperation she downloads the same AI app that ruined her life, because for better or worse, that’s her most real relationship.

Banerjee’s LSD 2, which was released in April this year, is even more unsettling. In 2010, the filmmaker gave us LSD (Love Sex aur Dhokha) which questioned the violation of our privacy through leaked MMS clips, found footage and CCTV cameras. In the last 14 years, the script has been flipped. In LSD2 we see how people now willingly perform for the cameras, putting their lives on display for more likes and shares, and being handsomely rewarded for it. The collection of three stories touches upon the Metaverse, deep fakes and trolls, and Banerjee assures us that no one’s coming out of this unscathed. Filmmaker Prateek Vats who wrote the film along with Banerjee and Shubham, says the idea was to tell a story not only about the internet, but how it “intersects with the state, democracy, caste and class”.

The first story in LSD2 opens with a Bigg Boss-style reality show called ‘Truth Ya Naach’ that claims to be superior to other shows because it gives its contestants the option to go off camera when they need some space. This of course comes with riders—the more time you spend off camera, the fewer the votes. A frontrunner of this contest is Noor, a transwoman who needs to win this to fund her sex reassignment surgery. To tip the scales in her favour she brings in her estranged mother on the show. In a hilarious scene scripted by the producers of ‘Truth Ya Naach’, Noor slaps her mother on television as viewers from small town India watch with their jaws to the ground. Woke internet commentators get their two minutes of fame by screaming, “This is patriarchy.” There’s also a YouTuber called Angry Mahima doing reaction videos of the episode from her bathroom. It’s equal parts funny and disturbing.

Influencers are fascinating subjects for screenwriters. But there’s also the risk of judging or mocking them. In Kho Gaye Hum Kahan, Lala is a beautiful influencer whose entire life appears to be a sponsored holiday. It’s hard to feel happy for Lala because we also know that she is secretly dating her gym trainer who she doesn’t want to acknowledge on her manicured Instagram feed. Director and writer Arjun Varain Singh says that if given a chance to make a spin-off film on Lala, he would write her with more empathy and lend more insight into her choices. We do get a glimpse of that in the final act of the film, but only briefly.

“It is important for us to look at it as their work. Influencers are people who are putting themselves out there. They are the commodity and the pressure of putting out a video every day is a lot,” says Vats. Sampath agrees. He adds that it was important to show a difference between the persona Nella adopts for work and who she is outside of it. Much later into CTRL, when we learn that Nella is short for Nalini Awasthi, it humanises her. That said, both Sampath and Motwane felt “two middle-aged men in their late forties” weren’t equipped to flesh out the details of Nella’s influencer life. They reached out to stand-up comic Sumukhi Suresh to write the Gen Z dialogues of the film and bring authenticity to NJoy—the YouTube channel that Nella and her boyfriend Joe run together.

Vats says he had to trick his search algorithm into opening his world to the uglier and crazier parts of the internet. The final story of LSD 2 is about a foul-mouthed 18-year-old gaming influencer called Game Paapi. He is an interesting choice of character since influencers on screen are usually ditzy women who talk about fashion and makeup. Game Paapi comes from a different corner of the internet. He is the son of a tuition teacher who earns enough money from his channel to fit an air conditioner in his kitchen for his mother. He’s a bully, who is also being bullied by homophobic trolls. “With the internet becoming cheaper in the country, the kind of people who use it now, is quite different from what it was 10 years earlier. I realised what a big loss Tik Tok must have been for creators who don’t fit in on Instagram which is about prettier faces and prettier clothes,” he says.

Given the vastness of the digital space and our worsening addiction, we are likely to see many more stories about this world. But the lesser-known fact about such films, and perhaps why we’ve had fewer of them, is that they’re hard to make. The opening credits of Kho Gaye Hum Kahan give us a quick recap of the friendship three Mumbai friends share through a busy montage of reels, Snapchat filters and Instagram posts. Social media apps are optimised for shorter, vertical videos but recreating them for films is not easy.

In another scene, we see Panday’s character Ahana stalking her ex-boyfriend by investigating his social feed. It starts with a harmless photo of a cupcake. She clicks on the accounts that have ‘liked’ the photo and lands up on the page of the bakery that made it and then the girl who owns it. In a few swipes she realises that she’s the new girlfriend who has replaced her. “There’s a lot more work that goes into this than people realise. A lot of it was done in pre-production so when the actors were using their phones, they were looking at fake profiles that we had already created. I also had to get the aesthetic right because I don’t like how most movies do pop ups or text messages. So, when we were shooting the phone, my cinematographer and I designed it in a way that the glow of the phone would look like a candlelight and then the actual information on it was put in later,” explains Singh, and then adds, “Honestly, it’s hell. When I saw CTRL my heart went out to that team.”

CTRL and the 2020 Malayalam film C U Soon by Mahesh Narayanan are the only Indian films made entirely in the screen life format—a form of visual storytelling in which we witness everything through digital screens. CTRL was shot in less than 20 days but took over a year in post-production to construct. At any given time, there are multiple things happening on screen. A video is posted, comments start popping up, Allen the AI bot is speaking, while an email is being sent on another tab. It’s a visual translation of our chaotic online behaviour, and antithetical to the traditional grammar of filmmaking where one scene seamlessly flows into another.

According to Vats, to be able to tell more such stories, one must discover appropriate visual forms, which is yet to happen. Till then, both he and Sampath hope that the message people take from their films is not as simplistic as ‘AI is bad’. “I think what one is trying to say is that they’re human beings behind AI. So the bigger question is who is building it, what is the ambition, and what biases are they feeding it with,” explains Sampath. “I guess we’re just asking people to be more mindful,” he adds.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Indian Companies Have a Ransomware Vulnerability Open

Liverpool star Diogo Jota dies in car crash days after wedding Open

'Gaza: Doctors Under Attack' lifts the veil on crimes against humanity Ullekh NP