Reign of Evil

Reduced to caricatures in Hindi films, Bollywood baddies are now turning South to take villainy to new heights.

Rahul Jayaram

Rahul Jayaram

Rahul Jayaram

Rahul Jayaram

|

21 Apr, 2010

|

21 Apr, 2010

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/cinema-evil-1.jpg)

Reduced to caricatures in Hindi films, Bollywood baddies are now turning South to take villainy to new heights.

In early 2002, Mukesh Rishi endured what he considers his “most uncomfortable” moment as an actor. On the sets of Telugu flick Indra, he was spitting fire in dubbed Telugu at reigning Andhra superstar Chiranjeevi. At one juncture while filming—Rishi playing the bellicose ‘zamindar’ and Chiranjeevi ever the age-defying mass hero—something “unbelievably disturbing” seemed to unfold. The director explained the subsequent scene. In the upcoming frame, Chiranjeevi would finish off both Isaac Newton and Usain Bolt in one blow: he’d jump on the road and roll on the ground to save Rishi’s school-going son from a truck at full speed. But Rishi wouldn’t melt. Indeed, he would have to kill his own son as the child was “touched by the hand of his enemy”.

Rishi had led a fascinating, if tough, life so far. He had grown up in Jammu, had run a stone-crushing business in Bombay, later gone to New Zealand, where he walked the ramp and got married to a Fijian of Indian origin. He returned to India in the late 1980s, first to debut in Bengali cinema, and then work in Hindi films before taking up Telugu assignments in the 2000s. But even he, with experience as rugged as his countenance, hadn’t heard something like this.

“I told the director, ‘Sir, this is wrong. I’m not comfortable doing this.’” The Telugu moviemaker, Gopal B, did a Raj Thackeray on him. “You’re from the North, you wouldn’t know what clicks with an audience in the South. Do as I say.” Rishi obeyed. He went on to impale the innocent child with a sword in front of his family. As cinema, it was intended as a display of brutal feudalism. In truth, it seemed to put actual ‘zamindars’ in the shade.

Months later, Indra released and was a blockbuster. Chiranjeevi roared through Andhra’s cinema halls. Rishi’s performance got noticed, and the scene had its intended impact—it had the state’s cinema-goers petrified. Rishi even watched it on a big screen in Hyderabad to gauge crowd reaction. “Emotions in India,” he now recalls, “have their own geography. A scene like that wouldn’t have worked in a Hindi film. Emotions are different in South India and North India. On the big screen, we can show violence here that won’t be accepted elsewhere.”

At any rate, in reconciling to the fact that on-screen aggression has geopolitics of its own, Rishi appears to have arrived. Over the last decade, he has carved for himself a niche of sorts in Telugu cinema. So well-established is he now in Tollywood (Andhra film industry) that even his pigeonholed image as cinema villain no longer sticks. In the 2003 Telugu hit Okkadu, he played the likeable-but-trapped policeman/daddy of the hero in a love story. “I can say that I’ve actually grown as an actor, not villain, due to films in the South. Even some of the negative roles have not been cardboard cut-out baddies.”

Echoing such vicious concerns is Sonu Sood. Sood had his film apprenticeship in the South, in the Tamil and Telugu movie industries, before breaking through in Bombay. Last year, he brought to baleful life the role of an Aghora in Telugu filmmaker Kodi Ramkrishna’s Arundhati. The movie has a mise-en-scene where blood is part of the design set and bloody-mindedness the one human merit separating the chaff from the grain. Sood is in a tussle with Southern leading lady Anushka Shetty for a revenge that goes back to their previous lives. In that life, Sood was a man who went berserk in the village molesting innocents, and Shetty had him sent out of the world—only for Sood to get tantric booster shots. He returns to haunt the village in this life. Therefore, Shetty cavorts in a special dance fused with martial arts to lure the Aghora Sood. She then proceeds to chop off his tongue, ending his incantatory prowess. Pinning his hands, she ultimately cuts off the ropes of a chandelier, which smashes on his body. End of story? No, no, no. We’re made to wait for a ritualistic finale that may be the mother-of-all retribution scenes.

Talk about Arundhati, and Sood’s timbre goes up a register. “No question. It was the hardest, most challenging and most satisfying role I’ve done. It was the most difficult 250 days of my life. It would take me four hours to put on the make-up and nearly one hour to scrape it off. I was living on adrenaline while doing that role. What mainstream film in India can do away with the idea of a male hero in an action/thriller/mythological film?” he asks. Arundhati stormed the halls in 2009. And Sood won the Nandi Award (Telugu cinema awards) for Best Villain.

Rishi and Sood are not orphans in the business of southern wickedness. Perhaps the first of a generation to have gained some traction in Bollywood and then headed down South has been Ashish Vidyarthi. His acting curve has travelled quite an arc from the time of his National Award-winning part in Drohkaal in 1995. (Whether that arc is an upward or downward one, though, is anyone’s guess.) “Over time, I did find myself typecast as a villain in Hindi cinema,” says Vidyarthi. “I was doing just fighter-type roles or over-the-top comic-villain characters that were beginning to bore me.” Vidyarthi, though, hasn’t limited himself to just the South. He’s even acted in Bhojpuri and Bengali films.

Ditto for Pradeep Rawat (who plays Ghajini in Ghajini); he did the same role in the 2005 Tamil ‘original’ with Tamil actor Suriya and Asin. Other notables include Marathi actor Sayaji Shinde, who has travelled far from doing just negative roles. In 2000, he played the lead in a critically-acclaimed biopic about the famous Tamil nationalist poet Subramanya Bharati. And, model-turned-actor Rahul Dev, too, has done his level-best to rape, scrape, punch, scowl and scream in Telugu and Kannada movies over the last decade. Sharat Saxena (the baddie in Aamir Khan’s 1998 Ghulam) and Puneet Essar (yes, the man who punched Amitabh Bachchan into St Philomena’s Hospital in Bangalore) were the early migratory birds of villainy.

So what has caught on? Why are we seeing so many artistes from Bollywood in the South? What’s the fascination for filmmakers here with talent from Bombay?

“I think the villain as North Indian is part of the current formula of films in Telugu at least,” says Rishi. Is it due to a paucity of local talent? Rishi disagrees. So does Pradeep Rawat. “Even I can’t figure why I am required. But from the ongoing demand for us, I can see that southern action films like larger-than-life negative character actors. More than acting skills, they’d like burly, majestic villains, who can scream and shout,” says Pradeep Rawat.

“No,” disagrees Rahul Dev. “Hindi cinema is quite popular in Andhra. People in Hyderabad and the rest of central and north Andhra understand Hindi and Urdu, unlike people in Tamil Nadu or Karnataka. People here watch Hindi films, so they already know our faces. The current trend is for villain-type characters from the North. But that won’t click with a Telugu audience due to a director’s whim. It’s because the connection between the villain and the crowd has already been established. Viewers already knew me or Mukesh Rishi or Ashish Vidyarthi before we made films here.”

But is there more to all this than meets the fleeting eye? Did roles start petering out in Hindi cinema for the likes of Rishi, Dev and Co? “There was a time when Amrish Puri or Pran commanded as much respect as the hero,” complains Rishi. “Over the last 10-15 years, the importance of the villain in Hindi commercial films has shrunk. One gets only stock characters to play. The hero and heroine in commercial cinema have become everything. A Boman Irani does interesting characters that aren’t completely black, but that’s an exception. Also, the characters and scripts in the South seem a lot meatier, though not always very good.”

Working in an alien language has its oddities and hurdles. Most of these artistes don’t speak any of the languages. Sometimes, many rely on writing out dialogues in Hindi or English. The assistant director trains them on how to mouth the words, and on what it means. “Thank God for dubbing,” says Rahul Dev.

As an artiste, Vidyarthi finds it educative to be in circumstances where every body cue of a local hanger-on on a film set becomes significant for him to understand what’s happening. “I’m terrible at languages. English and Hindi are as far as I can get. Though Malayalam is my mother tongue, I can’t speak a word if it.” What does he do in a Telugu film then? “Since I don’t know the language, I become even more focused and my senses are more heightened at work. This is in addition to what I’m preparing for in a scene.” Vidyarthi has had 90 releases across languages (including Hindi) in the last nine years. Of every 10 days of work, he spends six in Bombay and four in the South.

Pradeep Rawat admits to his struggles with a new language. He even reads self-help manuals and booklets like ‘Learn Telugu through Hindi’ that one finds at railway stations. He’s very worried that he shouldn’t speak “ashudh bhasha” in any of his non-Hindi films. “My co-actor and friend Sayaji Shinde does his own dubbing in Tamil films!” he mutters, grudging Shinde this ability. “It’s very difficult, but I want to break the language barrier soon. Directors give me work as I have a good voice. I want to justify their faith in me.” Rawat, like Sonu Sood, won himself a Nandi Award for Best Supporting Actor for the rugby-based film Sye in 2004. In Bollywood, he hadn’t done anything apart from playing the goonda, smuggler or pimp.

However, all the curiosity, sense of creative ‘challenge’ and recognition is one thing. The hard facts of the rat-race that is the Hindi film world are what really hurt. Rishi is blunt about it. “In commercial Hindi films, non-star artistes like me aren’t ever part of the publicity blitz for a film, though we are as much part of the movie.” Often he says, a Hindi film with a big star cast will mean the money that is due to him will take six months to arrive. And, “In Bombay, you don’t even get called for Filmfare award functions. Not that it matters,” he mutters. Work in a Telugu film means fast work and faster money. “If they say 30 days of shooting in Hyderabad, it means just that. My cheque comes to me around two months after I’ve done the film,” he says, while recounting some tough times in Bombay.

Rahul Dev knows fully well how Bollywood behaves with its “side actors”. But that won’t stop him from being on the prime platform to display one’s acting wares. “The money, the fame, the recognition, I doubt will be as good if you do well in a South film. Granted, there’s some great work happening there. But the South film, no matter how good it is, is by definition restricted by language and region.”

Villainy, in Hindi films or the South, is a kick for the aesthete inside. Evil is so much more interesting than good. One actor (who didn’t wish to be named), very much a part of this trend, was asked if he would swap roles and play hero. Out came an answer referring to one of his idols.

In March 1999, he recalled, celebrated British actor Steven Berkoff was in Bombay for his one-man show at NCPA called Shakespeare’s Villains. After a sassy performance at the NCPA, he had to face some asinine questioning and Bollywood reportage. One woman asked him, “Sir, don’t you think you’re stereotyped as a villain?” Berkoff fixed his sweat-laced face and serial-killer gaze on her. “Villains, my dear,” he said, pregnant pause and all, “are far more interesting than heroes. Heroes are fools.”

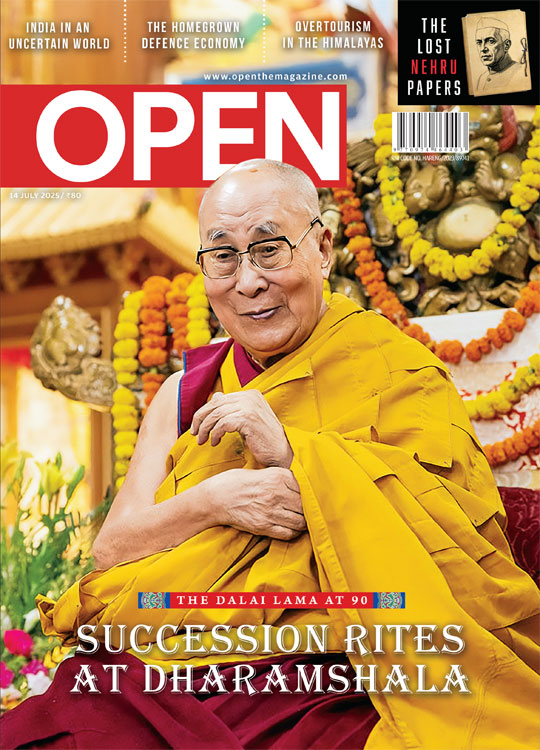

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Dalai-Lama.jpg)

More Columns

From Entertainment to Baiting Scammers, The Journey of Two YouTubers Madhavankutty Pillai

Siddaramaiah Suggests Vaccine Link in Hassan Deaths, Scientists Push Back Open

‘We build from scratch according to our clients’ requirements and that is the true sense of Make-in-India which we are trying to follow’ Moinak Mitra