How he ‘inadvertently’ put another poet’s works in his collection and why the episode remained unknown

In the late 1990s, a 17-year-old youth in north Calcutta inherited an olive green trunk from his maternal uncle. The small and heavy iron chest bore no insignia and was sealed with a sturdy egg-shaped lock. The key to the lock was missing. He was told the trunk was a gift to the family from Nandita Kripalini, granddaughter of Rabindranath Tagore. It had changed a few hands through the generations.

The mention of Tagore aroused his curiosity. Having failed to break the lock after several attempts, he hired a locksmith from across the Ganga in Hooghly district. Inside the trunk, there were a few ancient clay coins, an English punching machine dated 1835, old British stamps, a small silver aphrodisiac container from the reign of Bengal ruler Ballal Sen (1159- 79 CE), an antique copper kosha (water dispenser), a one-mouthed rudraksh bead, the first printed edition of Tagore’s poems, Sphoolinga, a rare Pashmina shaaler-sari (shawl sari), a printed 1903 edition of Abraham Lincoln’s autobiography, an old Bengali edition of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat in colour, a kushti stone plate with a footprint of Vishnu and the second edition of Alice in Wonderland printed in London in 1946.

There was also an undated tear-out from a Bengali magazine Desh. It was an essay by Partha Basu titled Byartho Raater Tara which made a critical assessment of the works of Priyambada Devi, a contemporary litterateur of Tagore. The essay, which appeared in the 25 January 1997 edition, mentioned Tagore including a few poems by Priyambada among his own notebook of poems Lekhan. Along with the essay, in the trunk was a small withering lithographic manuscript bearing a signature of Tagore in gold ink. The cover read ‘Lekhan [by] Sri Rabindranath Thakur’ in Bengali. Inside, there were 70- odd pages (some left blank to serve as separators) of fragile yellowing paper, and Tagore’s unmistakable handwriting in Bengali and English, neatly arranged in his unique way of writing verses, with animal-like pen-and-ink doodles running over his corrections. The opening page read the same as the cover but this time in black ink with the addition— ‘Budapest, 26 Kartik, 1333’ (10 November 1926 in the English calendar). There was one more thing in the trunk—a black- and-white photograph of Tagore dated November 1926, Balatonfüred, Hungary, on the obverse side in black ink.

At the time, the 17-year-old did not pay much attention to it. The trunk was closed and stowed away. Thus, it rested for 15 years.

In 1926, Rabindranath Tagore visited Balatonfüred, Hungary, where he developed a heart ailment. The doctor advised him rest for a week in the salubrious environs of Lake Balaton. It was during this period that he wrote Lekhan in a notebook. There were 388 small English and Bengali verses in it. Most of them were a collection of past thank-you notes to admirers. In the introduction, Tagore wrote: ‘The lines in the following pages had their origin in China and Japan where the author was asked for his writings on fan or pieces of silk.’

Lekhan was first published in Berlin in 1927 through a new technique that reprinted handwritten words on aluminium plates. Tagore sent a facsimile ‘personal’ edition to Priyambada Devi, herself a poetess of note in India. On reading it, she noticed a few verses as her compositions. Alarmed, she immediately wrote a letter to Tagore, subtly letting him know about his ‘mistake’. It is not known what Tagore’s reply to her was, but he acknowledged the error in an essay that was published in Probasi in November 1928. He wrote (translated from the Bengali):

‘Upon reaching Germany, I learnt that there was a way handwritten words in a book could be printed in the same form using a special ink and aluminium plates…

I was very unwell then, and thus had plenty of time to sit down and put down these English and Bengali writings…

In the meantime, a very good friend of mine told me—“You have written so many small poems in the past. I request you to use this opportunity to preserve them.”

I knew I had the propensity to write and forget, and there had always been a self-deprecating anger in me for this forgetfulness. So with my consent, my friend collected a few small poems and brought them to me.

“I cannot remember if all of these are my writings,” I said.

“There’s no doubt about that,” he replied.

There had been instances in the past when I had often forgotten about my own poems… Thus, I had to agree that the few poems he had collected were mine. When I read them, I thought I had written them very well…

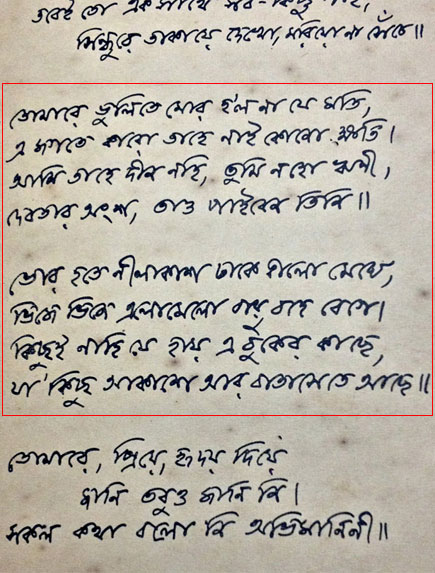

When I read—

Tomaare bhulite mor holo na je moti, / E jagote kaaro taahe nei kono khoti. / Aami taahe deen nohi, tumi naho rhinee, / debotaar ansho taao paaiben tini

(I could not set my mind to leave you,/ no one in this world loses from this / It does not make me poor, nor you debtor / One gets even God’s share)

—I saw this as my writing. I had to agree that the poem had fulfilled its fullness in its brevity. I felt like expanding it to 25-30 lines for greedy readers. It could even be easily written in bigger text to fill up space. But I restrained myself…

Another poem after that:

Bhor hotey neelakaash dhaake kalo meghe/ bhije bhije elomelo baayu bohe bege/ Kichhuee naahi je haay e buker kaache/ ja kichhu akaashe aar bataashete aachhe

(The azure of the sky gets covered with black clouds at daybreak/wet scattered breeze blows fast / O! There is nothing near my bosom / Only the sky and the breeze have everything!)

Well done, I said to myself again. The way the emptiness of the heart, and the sky and air outside together have erupted in laughter —who else in Bengali literature can say this with such facility? The fact that a common reader will not be able to grasp the beauty of this was the reason I resisted emphasising it further…

Another poem:

Aakashe gahono meghe gobheer garjon / shraboner dharapaate plabito bhubono. / Keno eto tuku naame sohaager bhore / daakile aamaare tumi? Purno naam dhore / aaji daakibaar din, e heno somoy / shorom sohaag haasi koutuker noi. / Aandhaar ombor prithibi pothochinhoheen / elo chirojiboner porichoy din

(Darkening clouds roar deep in the sky / Sravan’s deluge inundates the earth / why did you caress me by my sobriquet? / Today is the day when I need to be called by my full name / at such a time, reticence, fondness and mirth are not to be ridiculed / darkening sky and earth appear pathless / here comes the day for the introduction of a lifetime)

While writing Manasi (his 1890 collection of poems), which is not talking about a recent period but a distant past, I remembered having written a couple of verses in the same vein. But unknowingly, the feelings here have found the same light even in its brevity.

Another small poem:

Probhu, tumi diyechho je-bhaar / Jodi taaha matha hote ei jeeboner pothe / namaiya rakhi baar baar/jeno ta bidroho noi, kheenshranto e hridoyo, boloheen poraan amaar

(O Master! The burden Thou hast given; if that I droppeth my head in the journey of life, time and again, knoweth thou that it is not a rebellion, my heart is weak and wary my soul layeth defenceless)

The writing is so candid and that’s the reason the tumult inside has found a vent through the rain-weary juhi flowers in full bloom. With contentment and pride, I copied these few poems on the special aluminium plates in my own hand- writing. At that time, these poems got included with my other poetry and got published in my book of poems entitled Lekhan.

A few months ago, I had sent a volume of Lekhan to Srimati Priyambada Devi. Let me reproduce her letter here: ‘I read Lekhan. Some small poems in it are wonderful— complete in just two or four lines. They shone like dazzling gemstones. I also noted four of my poems printed in their entirety on page 23 of Lekhan, and the first two lines of another poem. These verses are:

1. Tomaare bhulite mor holo nako moti

2. Bhor hotey neelakaash dhaake kalo meghe

3. Aakashe gohono meghe gobheer gorjon

4. Probhu, tumi diyechho je-bhaar

5. Shudhu eituku mukh oti sukumar (first two lines)

These have all been published in Patrolekha in 1908. But, please do not share this matter with anyone else.’

It was then that I remembered when I first read the manuscript of Patrolekha, Priyambada’s non-ornamental and non-exaggerated poems came in for praise from me. I realised that those poems had not been given their due respect. My mistake in writing the poems from Patrolekha in my own handwriting and giving it place with my own poetry to project my respect makes me happy.’

Probasi, Karthik 1335 (November 1928)

When Lekhan was reprinted by Visva Bharati University in 1961, these rogue verses were removed. Referring to this, Tagore expert William Radice writes in the introduction of The Jewel that is Best, Collected Brief Poems: ‘[When Visva-Bharati reprinted Lekhan], by mistake, one of Tagore’s own poems was removed too, probably because it was on the same page as the five rogue poems. It was restored in the Rabindra Rachnabali.

Lekhan is Tagore’s only bilingual book. It contained 142 poems both in English and Bengali, 47 in Bengali only and 88 in English only. Tagore was already well experienced at writing English versions of his brief poems, or sometimes writing directly in English, for in 1916 Macmillan in New York published Stray Birds, a collection of 326 English aphorisms.’

In the first modern printed edition of Lekhan, published by Pulinbehari Sen, Visva Bharati, a note in the beginning says: ‘…there have been requests from many to reprint Lekhan’s collection of poems. On this popular demand, we are printing an incomplete book of the first edition. In this book, there are pages missing from the original edition. We hope that this edition will nevertheless be liked by you because of the ‘hints of personal identity’ of the author.’

Dated: 7 Poush, 1358 (21 December 1951)

Last October, the inheritor, who is now 32 and also an avid philatelist, decided to take stock of his collection. It was then that he revisited the contents inside the trunk. He read the Lekhan notebook and the magazine tear-out. He came from a family where Tagore was deified, and to him, it seemed that the inclusion of Priyambada Devi’s verses in Lekhan under Tagore’s signature and byline was plagiarism by modern standards.

But it did not diminish his family’s love of and respect for Tagore. He says, “He is there in every aspect of our daily lives. This incident was a minor aberration, which, as they say in Latin, was either lapsus memoraie (a slip of the memory) or lapsus calumni (slip of the pen). Tagore’s greatness lies in the letter of apology to Priyambada Devi.” With that, he partly closes his eyes and bows his head lightly toward Tagore’s photo hanging in his visitor’s room.

(Verses translated by Bina Biswas; other translations by Arindam Mukherjee)

More Columns

BJP attacks Cong leaders over loose comments on terror attack Open

Afghan snub to Islamabad, India bans 16 Pak YouTube channels Rajeev Deshpande

Andolanjivi Tikait brothers bay for hostile neighbour Siddharth Singh