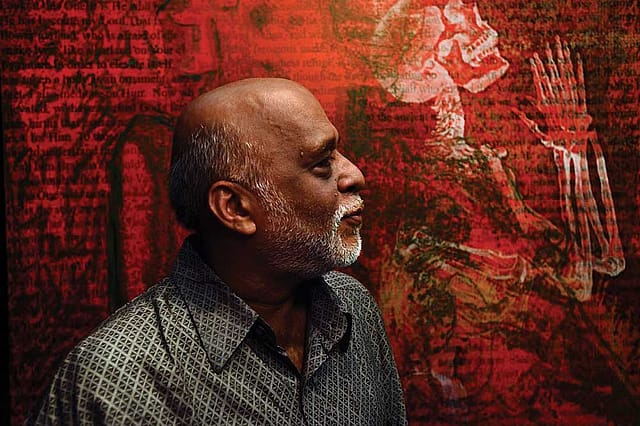

V Ramesh: The Hyper-Realist

"ARE YOU SITTING on the edge of your couch or a seat?" V Ramesh asks me. I am, but the person on the other side of the phone is in Vishakhapatnam and shouldn't know that. "Call me whenever you want," he continues affably. "Except between 1:30 and 2:30. That's my siesta time. I don't have my chair, so I can't paint right now. I just go and sit in my studio."

Ramesh's favourite chair is in Delhi for an exhibition. It's perched in front of an oil-on-canvas painting of him in the same chair; as is his dresser, mirror, calendar, marble-top table and a few books from his studio, including a book by Salim Ali on birds and John Berger's Bento's Sketchbook. On the opposite wall hangs a note detailing stories that his grandmother told him as a child that influenced him all through his life. Soft strains of MS Subbulakshmi waft through the air, as does the smell of linseed oil and incense.

The walls are graced by three distinct kinds of art. There are hyper-real, sensual watercolours of fruit, some surrounded by lighter lines showing human viscera; sparse images of dogs sleeping peacefully at Maharishi Ramana's Ashram; and three big oil-on-canvas paintings scribbled over with lines and colours that are based on stories from the Ramayana. The Moment of Epiphany is based on the story of Rama, Lakshman and Vishwamitra meeting Ahilya; Savdhaan is about Sita's kidnapping by Ravana; and The Genesis of an Epic is the tale in the Valmiki Ramayana about the origins of the epic—where Sage Valmiki sees the male krounchi bird being killed by a hunter and frames the first shloka.

2025 In Review

12 Dec 2025 - Vol 04 | Issue 51

Words and scenes in retrospect

Since it would be almost impossible to decipher these without a map, a small oleograph of the original image hangs next to each. The images draw your gaze again and again. In Ramesh's version, Ahilya towers over the young Rama and Lakshman, unlike the original image in which she is far smaller. In Savdhaan , Sita offers food to Ravana before she's kidnapped. Her face is obscured while the texture of her clothes is clear. In the top corner, Jatayu fights for Sita's honour. And in The Genesis of an Epic, the original figures of the two sages and the hunter are obscured by the battle between Ravana and Rama. The only figures visible in the centre of the painting are birds—one with an arrow piercing him. The scribbles and defacement give a sense of underlying violence to the image and imbue it with a fresh meaning.

The hyper-real watercolours are similarly troubling. Pomegranates that burst with blood, a bunch of bananas at the centre of the ribcage, fecund plants with meaty thorns and a broken banana plant branch called Fallen Warrior. Their realism is so perfect that someone at a show asked him if they were digital prints. "I should have poured a glass of water on them to prove that they were real," he says with a laugh. "It's not the magic of realism that's important. It's the ability to conjure up an intensely emotional landscape that moves you deeply. Perhaps I use realism because of that," he adds. I notice that no one stands close to these images of fruit and viscera during the exhibition opening. It's almost as if they are unconsciously troubling.

And then there are the dogs sleeping peacefully at Ramana Ashram. Ramesh says that he'd decided to do a series of 108 watercolours as a string of offerings to Maharishi Ramana. Since the series is called Devotees, they open up another interesting line of conversation for the spiritually inclined. "What's the role of dogs in the Eastern tradition?" someone asks. Problematic, it turns out. They're a symbol of attachment. And when the way to attain moksha is through non- attachment, they are unexpected, to say the least, in a religious painting. And yet, no one is at peace quite like a dog.

Ramesh started mulling over these paintings in 2015 and completed them in 2016, working on the oils and watercolours simultaneously because it helped him stay intellectually and mentally aware. The watercolours allowed him to show inner spaces and areas that are smaller and more intimate. On the other hand, the vast storyline of the Ramayana; its percolation and osmosis into today's society as well as its tales of underlying violence moved him and made him commit to the story again. An old book of Raja Ravi Varma oleographs which had 30-40 illustrations stoked his interest. Of course, Ravi Varma's women were equally troubling in their time, given their sexuality, and both Ahilya and Sita are a part of the 'Panchkanya'—women who are viewed as ideal women and chaste wives while at the same time being associated with more than one man, and breaking traditions. And Sita, our heroine here, is shown as faceless as Ravana. I read this as an analogy that points to the situation of women today and as an attempt to create a modern Rama Rajya—a utopian nation.

Sadanand Menon, the critic, once called Ramesh a 'fabulist', and his paintings 'tapestry-like, with multiple layers of submerged narratives, filled with deeply personal and cultural memory; the visual equivalent of a time-lapsed call of haunting voices across time'. They definitely force the viewer to think and engage with them. Menon also called him 'one of many artists who seem to have fallen through the cracks of modern Indian art history'. But today he's made up much of the commercial distance between himself and his compatriots from MS University, Vadodra where he studied.

"Over the years, I realised this layering of images till one arrives at the truth of the painting is a process that I enjoy. It has percolated into my very mode of working as a painter," says Ramesh. It's not only the layers of paint you have to penetrate, but also layers of metaphors and historical references that are packed into a single canvas. They engage with abstractions like divinity and death; and spin parables culled from sages, mystics and poets, while laughing at the impermanence of life.

'Remembrances of Voices Past' (a solo show held in 2015) included works from the start of his career, in the early 90s, when he brought his hyper realistic eye to the human body. His theme then was, 'the matter-of-fact heroism of the survivor who refuses to succumb to abjection or corruption, and who negotiates between vigorous activity and helplessness'. By the 2000s, his emphasis had shifted to the role of memory, bhakti and allegory. His paintings contained large, cosmological and legendary figures that were often larger than the canvas, or even the landscape, and he gave coded references to the stories he was inviting the viewer to encounter.

But arguably, the most memorable of his works is Sanctum Sanctorum: a Corner for Four Sisters, where he painted four bhakti poets who were born centuries apart but whose lives were all equally tumultuous: Lal Ded from Kashmir, Karaikkal Ammaiyar and Andal from Tamil Nadu and Akka Mahadevi from Karnataka. They all left home to wander as poet-saints and were equally reviled and revered for giving up their conventional roles in society. They were known for their insights into human existence, and their poetry was filled with passionate, intimate dialogues with their God.

Ramesh's luminous text paintings of these poets were genderless and intimate. He told their stories using text from their poems and images that they were associated with; for example, he used a jasmine flower to represent Andal. It was assumed that the viewer would know the myths and poems as intimately as the painter.

"To be able to draw the viewer within, through this state of flux and through the layers of paint and images… one has to adopt strategies and improvise modes of expression, which I do by borrowing from traditional narratives and using allegories. My work hints at areas of faith and it has articulated these ideas in an oblique manner using both imagery culled from mythology and voices from medieval poetry," Ramesh says.

How does his teaching interfere with or help his practice, I ask the artist who has taught at the Department of Fine Arts, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, for over 30 years. "I was a reluctant teacher, but now it gives me as much satisfaction as my creative work," he says. "Every time I have a show, they are my first audience. They get excited. It takes them on a different tangent. They raise questions that I may have forgotten. You try to find the answers within you which may be relevant even though they may not be easy, like 'What is the process that compels you to make a work?' They're often from underprivileged families and come from small towns, but they have an intense desire to be artists. To be able to tell them stories and open their minds is worth it. And they come back years later, telling me that a story stayed with them and gave them an epiphany." True to his word, he tells me a story within a few minutes of meeting me. It's a mythological tale by a man called AK Ramanujan. It's such an enjoyable tale, told with such enthusiasm, that I go home and order more of the great storyteller's exquisite collections of folktales and myths.

How does he know when a work is complete? "I ruminate on a work, sometimes for two years, before starting it," he says. "And once I'm done, I cover it up and come back to it after a week. If I feel happy, I know it's done."

(A solo show by V Ramesh is on at Gallery Threshold, Delhi, till 10th March 2017)