Snapshots of History

POSTCARD PERFECT' IS a popular description for a scenic view posted on social media. It is a rather ironic phrase in an age when writing and sending postcards are in decline. Yet, postcards have historically held much cultural capital, since their introduction in 1869 by the Austrian government. They would swiftly become a significant mode of visual communication across the world, being easy and cheap to send. The postcard is as much a window into the sender's mind as of the larger political, social, and cultural landscape they were written in.

The recently opened exhibition, Hello & Goodbye: Postcards from the Early 20th Century at Bengaluru's Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) trains its gaze upon colonial postcards from undivided India, drawing attention to the multiple roles postcards played during those times as well as compelling the viewer to meditate upon the very idea of the postcard itself. The exhibition has been made possible with support from the HT Parekh Foundation.

Khushi Bansal, a co-curator of the exhibition says, "The idea of doing an exhibition around postcards emerged after looking into our collection and forming a 'tiny objects series'. From a vast collection of tiny objects such as matchboxes, stamps and textile labels, we thought about beginning this series with an exhibition on postcards."

The curators Bansal and Meghana Kuppa especially wanted to highlight the fact that while people associate and use postcards as sentimental exchanges between loved ones, the postcard's historical value is often overlooked in the process. The idea of the postcard as a valuable historical document became an opportunity for the team to trace a visual history of India in the early 20th century, coinciding with the fact that postcards were at the height of their circulation during this time. Whilst working through this collection, the curators observed that the colonial history of the subcontinent was embedded in the nature of the collection. Hello & Goodbye tells viewers of the Western perception of undivided India, and offers a glimpse into life in the early 20th century. Through the 80-odd postcards, from the museum's 1,300-strong collection, we learn about both the visual and written messages of that time.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The exhibition opens with the question imprinted upon a postcard: "What travelled 7000 kms [distance between England and India], is 4×5 inches, and weighs 2gms?" This is an apt and self-referential opening to the show.

In one postcard series focusing on children, the note raises the question; "Oftentimes, people in history are reduced to facts and statistics, while the realities of children's lives remain untold. Postcards allow us to challenge that perception…do these images evoke any emotions or memories for you?" The series of postcards on children show a young woman covering a girl's long plait with flowers. In another, two boys in arms share a raucous laugh. In the most poignant one we read a message in a child's scrawl to his/her father who is in a distant land; "Dear Daddy, we are getting on all right and we hope you are all right."

As one examines the different kinds of postcards, one receives a snapshot of the sender's identity as well as the minutiae of their daily lives. The exhibition simultaneously encourages viewers to examine postcards as historical documents while engaging with the role of the postcard in delineating identity. For example, what was it like for the newly displaced to make a new home in an alien land thousands of kilometres away, and how and what would they communicate back home? The range of postcards on display provides a spectrum of exchanges.

A monochrome postcard of the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay seen from the sea reads rather drily: "The posh hotel in Bombay". A brightly hued postcard titled 'View of The Hooghly from The High Court' depicts tree-filled gardens adjacent to the river and reads, "This large open space is called the Saviour of Calcutta. In the great heat, it is the only place that the English can get a breath of fresh air. Calcutta is below sea level and a long way from the Ganges."

Postcards can also be seen as the social media posts of the past. One sender, Beth in Delhi, simply wishes to inform her recipient, Kitty in London, "I am not feeling very well today," while Charlie sends a simple birthday greeting to Nellie. "Postcards and social media platforms like Instagram share surprising similarities. Both rely heavily on visuals, with postcards serving as a historic example of this practice," Bansal says. Similar to character limits, the postcard writers had limited space for text, leading them to employ abbreviations, turning 'postcards' into 'P.Cs' and 'headquarters' into 'H.Q'. As a viewer we can easily draw a parallel between the character counts and abbreviations of online posts today. Postcards can also be read as tweets, given that unlike sealed letters subject to privacy, a postcard's message can easily be seen.

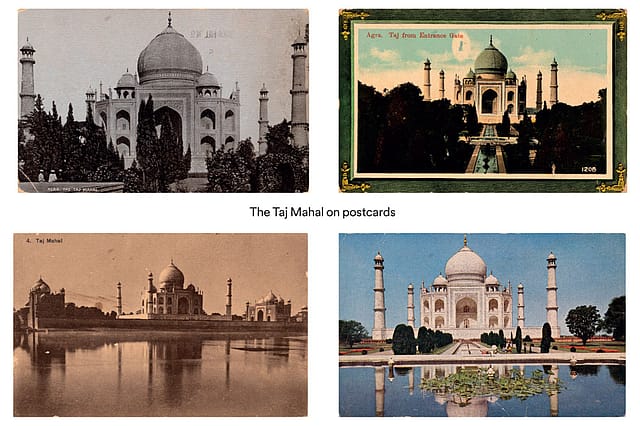

As most of the postcards at the exhibition were sent by the British or other foreigners living in India back to their country, they convey a stylised, self-conscious depiction of India, positioning it both as a country to be tamed and as a land of opportunity. For example, the Taj Mahal, which finds diverse representation in the postcards, appears to be a visual shorthand of a romanticised notion of India. Nautch girl postcards meanwhile perhaps contributed towards reiterating the idea of the exotic and the imagined female other. In one postcard featuring a nautch girl accompanied by musicians, the sender complains to his son, Donald, that her song, "sounds like a Trojan car that has had no oil for weeks" and that he doesn't know how fortunate he is to live in England and "not to be able to hear any Indian music." While this postcard might, at first, read just as a codger's complaint about an 'alien' culture, it also hints at how the coloniser saw the 'native,' and the message he passed on to those at home.

"Eventually, these political views trickled into daily communication, as several senders wrote messages tinted with racism and bigotry, hence allowing us to view these micro-histories in a different light," Bansal adds.

Indeed, for in the midst of witnessing the exchanges of the mundane, I was disoriented to encounter an example of explicit racism and bigotry in one particular postcard, where the writer refers to "n*****s" in relation to "(white) women of Delhi during the mutiny."

The curators reveal how prolonged engagement with the postcards made them see their different layers. "We could reflect on the larger impact colonial propaganda had in shaping opinions about India and as we consider postcards to be personal, and the personal is political, these postcards give us an insight into lived experiences shaped by activities of colonial expansion in the early 20th century," Kuppa says.

The exhibition also features a few postcards printed by Indian companies, which locals bought and sent to one another. While Marwaris, Gujaratis and Parsis were patrons of print culture in India, a larger population of the Indian elite across the subcontinent were the primary consumers of picture postcards. In their collection, they even have a postcard sent by an Indian from Amritsar to a friend in Paris, which also gives us an idea of the Indian elite having exchanges with people abroad through postcards.

A series of four delicately embellished postcards of Hindu deities in the Nathdwara style provides an insight into how women would purchase and decorate them to perhaps install in their puja rooms, each one entirely unique in the thousands of mass-produced prints. The postcards could have either been embellished by women at home, or alternatively, at the shop from where they were purchased. The embellishing became a way of immortalising gods and goddesses, dressing them as they would a deity at home with exquisite jewellery and glittery outfits.

In addition to the postcards displayed in the exhibition, a visitor can further engage with different kinds of postcards at an interactive feature, which allows them to browse through reprints. The contrast between the formal depictions of famed monuments such as Red Fort and the quotidian, seemingly banal messages on the other side particularly stand out as you leaf through one postcard after another. "The act of going through the reprints physically is unmatched," says Kuppa, adding that the curators also hope that people reconnect with the idea of sending postcards as a takeaway from the exhibition, whether it is to a loved one or even to themselves. Visitors can even create digital postcards or send a physical one from outside the exhibition space. MAP will also host talks and conversations around postcards along with workshops in the coming months.

MAP is known for uniting the international with the hyperlocal. Given that speciality, the absence of Bengaluru-related postcards is noticeable. "It's more so to do with the fact that our collection lacks the Bangalore angle. With that said, at that point, Bangalore was a cantonment city and so there were a lot of tight restrictions in place for their production," Kuppa explains, adding that they hope to loop back to the idea of Bengaluru through talks and heritage walks.

The exhibition design also evokes the atmosphere of an archival room, which in turn was influenced by the curators' own experience of putting together this exhibition. "We would sit for hours browsing through piles and piles of postcards. And so we really wanted our visitors to have the same experience. While browsing through them, you experience a roller coaster of emotions: joy, sadness, anger and this station allows for that," Bansal says. And indeed, this exhibition allows you to appreciate how a small, fragile rectangular piece of paper, winging across seas and continents, became a powerful vehicle of communication, and a record of history.

(Hello & Goodbye: Postcards from the Early 20th Century is on view at MAP, Bengaluru , till August 18)