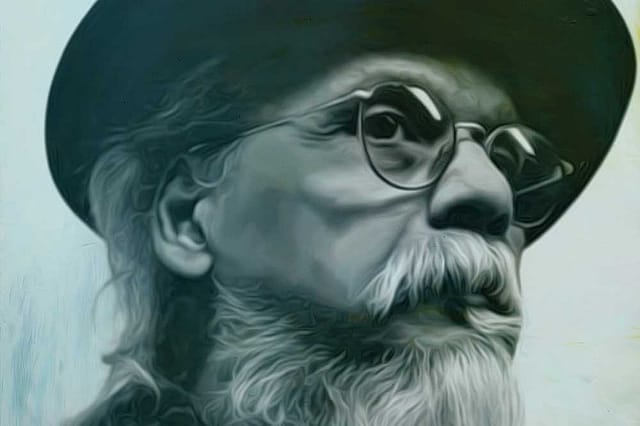

Mohan Samant: Picture the Outsider

MOHAN SAMANT HAD A conceptual grouse with the word 'practice'. As both musician and artist, it was simply not something he did. He preferred to unequivocally renounce the very notion of practice as a private disciplinary engagement. 'I do not practice the sarangi. I play it every day as if I am in a concert, sometimes very well, sometimes very badly,' he once wrote. 'Similarly, I don't practice painting with drawing and sketching. I just paint and if I don't like it I overpaint the same canvas twice, thrice, many times. I do not use drawings and sketches in preparation for the paintings, they are separate works altogether.'

By the 1950s, the 1924-born artist was proficient in both arts, though music predated his love of painting. 'Music became the focus of Samant's life early on,' notes Marcella Sirhandi in her essay on the artist who was born Manmohan Balkrishna Samant into a middle-class Brahmin family in Goregaon, Bombay. 'He first taught himself the flute, with which he accompanied a bhajan group ensconced in the Samant wadi. When he got bored, he quit the sessions, but he was soon enticed by one of the performers into buying a broken dilruba.' If he could fix the instrument—a cross between a sitar and a sarangi—the musician would teach him how to play. Money was tight at home since his father had died, and Samant had to improvise. 'He went to a nearby village where there were horses and chased after them, grabbing hair from their tails for the bow,' writes Sirhandi. 'He then spent twenty-four hours repairing the instrument. When the dilruba was ready, Mohan played it day and night in the attic, so he wouldn't be disturbed.' Later, to lure an uninterested Samant into passing his school exams, his mother promised him anything he wanted. He laboured reluctantly for a month and successfully gave his exams. His mother bought him the desired sarangi.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Besides his family's collection of Raja Ravi Varma reproductions and tinted family photographs, Samant's exposure to his mother's craft fixation inclined him towards art. 'A photographic portrait of a very cute Indian or European crawling baby was pasted on a paper board and then cut out,' Samant wrote. 'My mother would dress the baby by pasting or stitching a variety of bright- colored cloth and artificial jewellery on the photograph, which would become as thick as three quarters of an inch. This was framed by a carpenter in a specially made deep frame to incorporate the thickness of the work… As an eight-year- old boy, it was a most intriguing concept to swallow, along with landscape and village scenes in miniature, never knowing that I would be incorporating all these cultural activities in my works of art.' His mother passed away in 1942, leaving him and his eight siblings orphans. His elder brother and two sisters grew concerned about his continuing obsession with art and music.

A chance encounter after high school, when he worked as an agent for the British War Effort Office, cemented his passion for painting. He had to check materials produced in small businesses around the city and one day, found himself passing a factory where huge cinema posters were made. 'There were mountains of very bright colors on a large palette with which they painted the posters,' Samant recalled. 'The sheer quantity shocked Samant, because the paints he purchased from the Bombay Stationary Mart were very expensive,' Sirhandi recounts. A vermillion watercolour tube two inches long cost almost 10 per cent of his monthly salary. 'One of the poster artists explained that the paints were made on site, but the colors didn't last more than a year or two and were very hard on brushes. He showed Samant the improvised palette knives the painter used, made from the springs of old gramophones. Samant followed his advice and found a metalworker to make a similar knife, both strong and flexible. With it, he began to experiment with more textured painting.'

His poster painter friend also introduced him to a more modernist sensibility divorced from realism, explaining how in his work he interspersed random scenes from a movie with casual irreverence for the laws of perspective. 'So, I had four things going on in my head. The handling of those large quantity of colours by painting with a knife, different sequences in a single painting requiring the distortion of perspectives, the spontaneity and structure of the painting, and automatic texture,' Samant later recounted. 'That was the beginning of my career and experimenting with a total disregard for any particular personal style, which I have fervently maintained throughout my life.' In 1947, Samant decided he wanted neither to go to college nor to an office. He enrolled at Bombay's Sir JJ School of Art and found a mentor in Shankar Balwant Palsikar.

At Jhaveri Contemporary's new Colaba-based gallery, a show of select works by Samant, titled Masked Dance for the Ancestors after his eponymous 1994 painting, suggests that for the artist, who was a member of the Progressive Artists Group, the notion of play contained more prophetic possibilities than practice. "Neither style nor theme dictates my art. I paint as I please, for I paint for the pure pleasure of painting," the artist once said, a quote the gallery has tactfully reproduced in its hand-outs to visitors. There is no other logic to explain the sheer range of materials, mediums, and references in Samant's art. It comes across as a collage of internalised techniques that range from Basholi and Jain miniatures to the frescoes at Ajanta to Indonesian wayang shadow puppets to their leather puppet counterparts regional to Andhra Pradesh to Egyptian Dynastic funerary wall drawings to African sculpture and masks, not to mention the whole gamut of Western Modernism, from the paper cut-outs of Henri Matisse's final years to Max Ernst's frottage. A quote on one of the gallery's walls offers a bird's-eye perspective of Samant's sweeping range: 'In my painting, I have swallowed the entire history of thousands of years and synchronised it into a modern idiom. Nobody can tell me I am a copyist because I am just as modern as anyone else except that my influences do not come from the contemporary art world; they come from the entire panorama of art history.'

Samant found success fairly early. In 1956, he won three awards—gold medals at the Bombay Art Society's annual exhibition as well as the Calcutta Art Society's exhibition, while the Lalit Kala Academy conferred on him the All India Art Award. He was also the recipient of a Cultural Exchange scholarship funded by the Italian government. But it was the Rockefeller cultural exchange fellowship in 1959 which altered the course of his life and legacy, for it took him to New York where he lived until 1964. He tried, unsuccessfully, for a visa extension, citing his success on the American art scene as collateral—by then he had given a sarangi recital at Carnegie Hall. He had already had three important solo shows at the World House, and was working out of a loft studio on West 21st Street in Chelsea and had dance critic and poet Edwin Denby, photographer Rudy Burckhardt and Willem de Kooning as neighbours. A photograph of him playing the sarangi, with two paintings from his exhibition at World House, appeared in Time magazine on March 6th, 1964. 'Like many young instrument painters fitted in with New York, Mohan Samant, 37, lives at an unfashionable address in a loft building above a street thrumming with trucks,' the article began. 'Unlike other young painters, he begins each day not at the easel but sitting shoeless and cross-legged atop a low podium, drawing out the eerie strains of his native Indian music on the sarangi.' A year later, Samant had his fourth solo at World House, featuring paintings he had left behind in New York. In India, he was featured in The Illustrated Weekly of India: 'Mohan Samant's success in America means a tremendous lot both to him and to modern Indian art,' the article read. In America, the solo found favourable reviews in New York Herald Tribune and ARTNews. Samant was perceived as being among few artists who successfully made the bridge between Eastern and Western traditions. In April 1968, a few months after a farewell exhibition at the Taj Gallery, Samant left Bombay for good. He died in New York in 2004.

Critics like Ranjit Hoskote who met Samant in his New York loft (he returned to the same apartment building in 1968, eventually moving in with his Australian musician wife Jillian Saunders whom he met in Bombay), have theorised that Mohan Samant was the missing link in the evolutionary narrative of contemporary art in India. 'A dislocated, but never disoriented pioneer, Samant spent most of his life in New York, exhibiting largely in North America and periodically in curated exhibitions in Britain and India,' Hoskote writes in his essay, A One-Man Avant-Garde and a History that Would Not Claim Him. 'The actors and stage managers of postcolonial Indian art could have embraced him as a valuable colleague and major contributor to their project at any time between the 1980s and 2000s, as the contemporary art scene in India began to assume a measure of self-confidence. But they did not, since they were (and, to a considerable extent, continue to be) unable to look beyond the national boundaries they had set for themselves.' Hoskote posits their understanding of the postcolonial was rooted in the ideological categories of autonomy and resistance, limited by a specific developmentalist history, and fixated on a misguided obsession with reconciling an elusive Indianness with a spectral modernity. They could not make room for a figure like Samant in their atlas, because they could not re- vision the postcolonial as the intensely contested, collaborative, pluralising, hybrid, self-renovating, and transcultural enterprise that it is. In 2014, however, Kamini Sawhney curated an exhibition of Samant's work at Mumbai's Jehangir Nicholson Gallery, which became a catalyst to the resurrection of Samant's legacy. It was here that sisters and co- directors of Jhaveri Contemporary, Priya and Amrita Jhaveri, 're-discovered' his work. 'We went on to research Samant's world and realised he had been edited out of the narrative of modern Indian art. Why hadn't we heard about him until now?' Priya Jhaveri says in an email.

Masked Dance for the Ancestors offers audiences the chance for a first-hand encounter with the complex immediacy of Samant's art. The selection spans a phenomenal range of media, and introduces audiences to Samant's penchant for building up a canvas layer upon layer until it assumes a multi-dimensionality that makes one question how a canvas can encompass sculptural, diorama-like elements while simultaneously seeming like an installation. The wire drawings make the figures embedded within leap out like animated beings while the impasto disguises and conceals so much drawn detail, it's impossible to digest within a hurried viewing. Your attention becomes mandatory.

(Masked Dance for the Ancestors is on at Jhaveri Contemporary, Mumbai, till November 24th)